A braided stream of histories in the Polish “Recovered Territories”

Agata Tumiłowicz-Mazur explores Karolina Ćwiek-Rogalska’s Ziemie. Historie odzyskiwania i utraty (Radio Naukowe, 2024), a study of Poland’s post-1945 border shifts, German expulsions, and Polish displacement. Through archival sources and settler memoirs, Ćwiek-Rogalska unravels competing narratives of displacement and memory. Tumiłowicz-Mazur notes that Ziemie points to the complexities and multiple narratives that weave the streams of memory surrounding these postwar events and places, bringing awareness to the difficulty the story presents.

And so we depart, on a journey to the lands of complex histories, convoluted narratives and dissonant heritage. Just like that, we pick up…well, not quite our humble belongings this time nor a suitcase, but a green hefty book. On its cover the rivers and its tributaries, like steady roots or pulsating veins, wrap around the western and northern territories of today’s Poland. If one of those streams touches upon the place of your birth, your heart might start beating faster. And if a thread of these lands runs through your family’s history, what’s also embedded there is a journey. Here to tease out the entangled threads of that transition is Karolina Ćwiek-Rogalska, a Polish anthropologist and trained ethnographer, who in Ziemie. Historie odzyskiwania i utraty [Lands: Stories of Recovery and Loss] (2024) asks an ambitious question: how to tell this story and do it justice?

At the conclusion of the Second World War, as the Allies redefined Europe’s borders, three countries moved westward. The Soviet Union annexed Poland’s Eastern Borderlands, the Oder-Neisse line became the new Polish western border, while millions of Germans were expelled into the new East and West Germany. Emerging from the trauma of war, displaced people needed to build their homes anew, in places unfamiliar to them. Ćwiek-Rogalska’s Ziemie zeroes in on the consequences of that dramatic change in the new Polish “Recovered Lands” and the long process of settling in. By working through scores of Polish settler memoirs, she uncovers the layers of that process and analyzes how it is remembered.

This is a story of post-1945 border shifts, the expulsions of Germans and displacement of Poles; a story of countries changing their shapes on a map and the resulting movement of peoples, of departures and arrivals. But it is also the story of what came after, the formation of new national narratives and the sloppy work of exorcising the delicate matter of memory. In the postwar bind between Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union, the destinies of civilians and soldiers became muddled, chaotically entangled, and therefore much more susceptible for the work of myth-making. Ćwiek-Rogalska, in a careful and detailed-oriented gesture, holds a magnifying glass up to this transition, while inviting in the voices of those who experienced it first-hand.

Meanwhile, scholars bend over backwards with the term’s propagandist tinge and dress it with quotation marks for a necessary distancing effect.

Dealing with the subject of the so-called Recovered Territories, or former eastern territories of Germany that became a part of Poland in the postwar aftermath, feels a lot like handling a living matter. It is as if it is still moving, coiling and recoiling in front of our eyes, impossible to pin down. There is hardly one word that manages to settle firmly and confidently when tasked with describing the complex reality. If I wish to be accurate, I need to tread lightly, provide an alternative definition, just like I did above, or maneuver between multiple “ors”, safe “so-calleds”, and multiple punctuation marks of which quotations are the most helpful. I do all that and stumble, just so I do not walk into the scattering of mines that crowd this subject. The perspectives abound, depending, of course, on who’s looking. The communists “recovered” the territories, referring to a fuzzy time in the Middle Ages when “those lands”, broadly defined, belonged to the also broadly defined Polish nation. Meanwhile, scholars bend over backwards with the term’s propagandist tinge and dress it with quotation marks for a necessary distancing effect. We no longer buy into enduring propaganda (or: some of us, of course, depending on who “we” depicts), but we are also at a loss for words to come up with a name that would pack all these variables appropriately into one, so we choose to stay with this term, “recovered,” the punctuation marks keeping us safe. There is hardly a common denominator. One needs to twist and turn, be able to tell the narratives apart, classify them properly, before departing to weave the story. Always already mindful of the trap ahead, of letting the reader assume the terms of the impending story as solid and unquestionable.

And this is the challenge from which Ćwiek-Rogalska departs. She takes up all the moving subjects and narratives surrounding the lands in question, and carefully teases out the terms of that conundrum. With her as a guide, we travel through whys, by looking closely at the decision-makers whose actions make the country of Poland shapeshift and move westward. In a rumination that stretches through ten chapters, the author closely analyses the governmental structures – the Ministry and PURs (State Repatriation Offices) – that navigated the bustling changes. With her we also travel through the hows, whos and wheres of the transition but the author never lets us off the hook – the awareness of the complexity of that process keeps us alert.

Those who came to the newly acquired territories by a stroke of destiny or in search of a new life lead the way and we follow. There was no confidence, no strong conviction

At first it is precisely that, the quandary of the ends and beginnings. For many, the Second World War ended, and a single gesture of redrawing the borders on a map determined new homes for millions of people across a swath of 850 kilometers. It is Stalin and his proverbial pencil. However, it is not just a single gesture but many, evinced in the meetings of multiple important political figures who first meet in Tehran (winter 1943) to discuss and then Potsdam (summer 1945) to make their words into flesh. It is the shifts of arguments, the commotion of meetings with no maps and struggles over the choice of the right river that from now on, with its splashing meanders, will be the waterway marking the borders of a new reality. But maybe it is not simply many gestures but countless ones, those of administrative workers on the ground who need to confront the reality of expelling millions of Germans while also resettling millions of Poles who must come in their stead. We see things taking shape and we see the growing pains of the narratives.

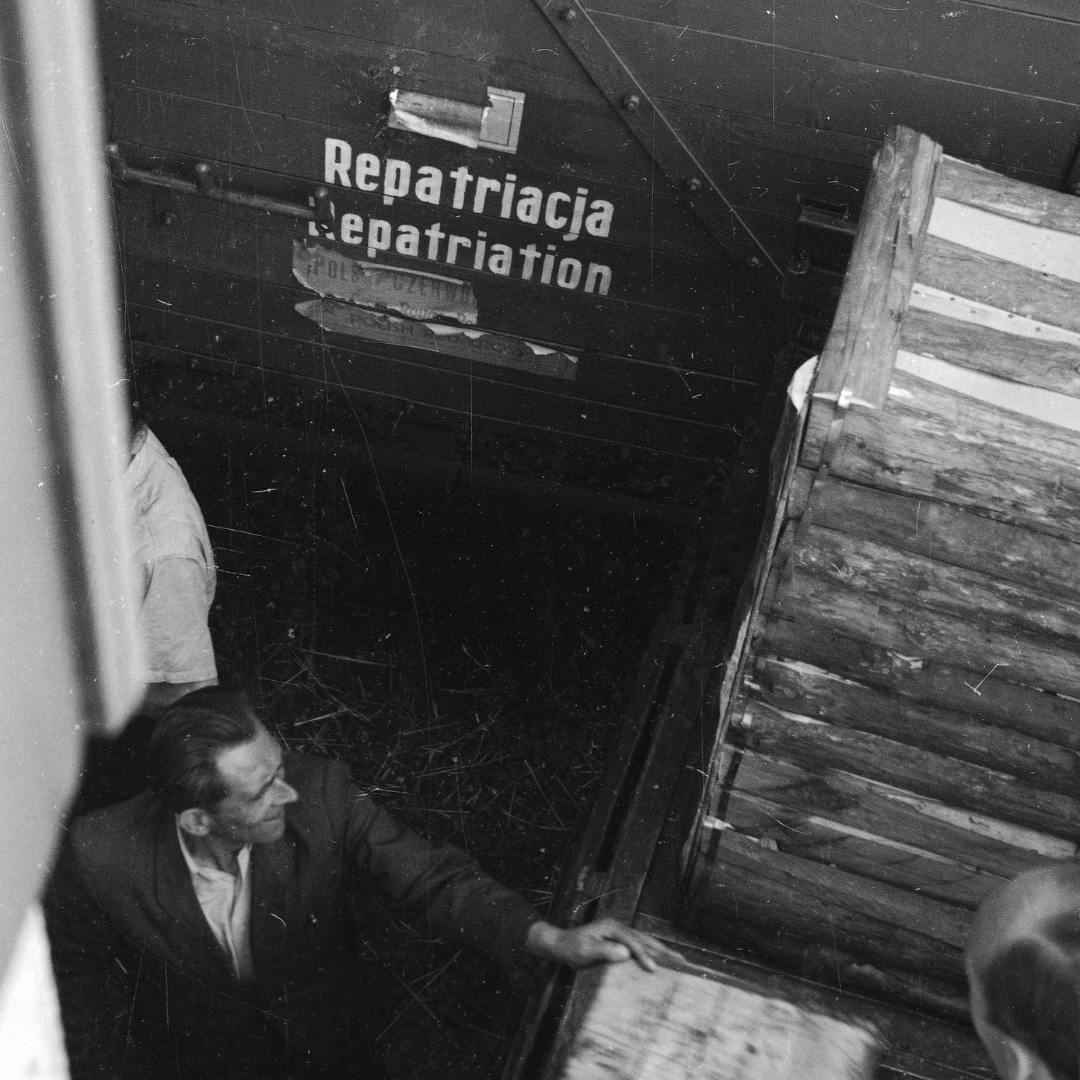

In order to find out how this postwar population movement was organized, Ćwiek-Rogalska peeks into the archival sources and conjures voices from memoirs submitted to nation-wide competitions. Those who came to the newly acquired territories by a stroke of destiny or in search of a new life lead the way and we follow. There was no confidence, no strong conviction; the settlers came bearing hesitation and doubts. “Should we stay here or continue to try our luck?” the Pawłowicz family wonders but then decides to get off the train in Stargard. “Everything was different here. The houses, the shapes of the townhouses, their appearance, the layout of the streets. And those walls: gray, ashen, brown. Completely different from those in our country.”1 The arrivals were difficult, and so were the departures. One of the displaced Germans remembered: “It felt peculiar—we were walking through what seemed like a native village, yet we saw only foreign faces and heard foreign sounds ringing in our ears.”2 In this kaleidoscope of experiences, what resonates are feelings of uncertainty, loss and confronting the unfamiliar.

The voices Ćwiek-Rogalska invites to her story, help us imagine fragments of the harsh reality of that transition. They guide us through the conditions that awaited the Polish newcomers at the PUR’s reception points scattered throughout Poland, at the crossroads of towns they did not know anything about or the thresholds of homes they had to inhabit. The spotlight is mainly on the Polish settlers who come from the lands just lost, from central Poland or from forced labor camps. But we also get to hear from the politicians and officials who clumsily attempted to rebuild Poland within new borders. We nearly see and touch the chaos of the moment as we try to parse through it along with the author.

We get to see the unexpected weight – and value – of the objects that are left behind but that are also set into motion by those who in the postwar years try to earn their living.

The case study is the author’s hometown – Wałcz (Deutsch Krone) in the region of Pomerania. Wałcz, the comforting point of departure and arrival, is at the same time a single drop in which wider historical currents are mirrored. However, the “where” of the book spreads to the regions of Silesia (Śląsk), Lubusz Land (Ziemia Lubuska), Pomerania (Pomorze), Warmia and Masuria (Mazury). But also: Schlesien, Pommern, Ermland, and Masuren. This is where the examined place gets more complicated. The memory of those who depart holds those lands in a longing embrace, but those who arrive need to sow their own seeds. We wonder whether the Polish equivalents of the German cities are their doppelgängers and whether 1945 was a veritable caesura for them. Do they somehow coexist? Can one city be suddenly stopped in its course while the other is poured out in its stead?

Movement carries it all forward. Because words, those signs we so readily employ for our purposes to shape monuments of ideas, give out quickly when confronted with motion that was set in the postwar reality at the very heart of Europe. So no monument is safe here, no statue everlasting. The complete chaos, confusion and breadth of outcomes is what defines the first years of that process. Through the book we get acquainted with settlers who look for their families but are unable to orient themselves as no one is quite familiar with the new geography yet. We get to see the unexpected weight – and value – of the objects that are left behind but that are also set into motion by those who in the postwar years try to earn their living. Finally, in a stellar penultimate chapter, we get to observe how possessions, lands and people are imbued with the weight of memory and how elusive this process is.

Somehow, this chaotic current is also what percolates through the invisible threads of the narratives that try to encapsulate it. The massive movement is what steers off course the many who depart on a quest to confront it. Eighty years later that motion is what excites, confuses, or sometimes remains inaccessible to those who have grown up in the comfort and familiarity of soft lines marking the shapes of countries on today’s maps of Europe. Ćwiek-Rogalska’s challenge to sound it out is an ambitious but necessary one as it fills an important opening left ajar on the native market.

Poles are not quiet when it comes to their Western and Northern Lands but it is true that the last decade made those voices louder, especially in the realm of Polish nonfiction offerings.

It is a common misconception to state that this subject in Poland became “popular only quite recently”. In fact, works of both fiction and nonfiction, weaved around the subject of displacement or set in the “Recovered Territories” have been steadily populating the market while scholarship has for years been quite abundant. Poles are not quiet when it comes to their Western and Northern Lands but it is true that the last decade made those voices louder, especially in the realm of Polish nonfiction offerings. Among those discussed most widely is Poniemieckie (also known as In den Häusern der anderen in Germany) by Karolina Kuszyk. Her approach is thematic, objects stand at the center of her inquiry, so does their loss and re-discovery. Kuszyk dives into sources, sketching the destinies of the German remnants in Polish hands, and while in the end the term itself, poniemieckie, formerly German, remains somewhat unexplored in its breadth, the experience of the inhabitants is central and dealt with respectfully.

This is not always the case for the recent works of other non-fiction authors, those outside of the scholarly realm, who chose to tackle the subject with levity. While Ćwiek-Rogalska and Kuszyk go back to the sources, Zbigniew Rokita and Sławomir Sochaj seem to espouse a conviction that there is just one story that needs to be told, one explanation that will enlighten the masses. In Odrzania, Zbigniew Rokita travels – of course, movement is key, even here – through a handful of places in the “Recovered Territories”. He chooses them at random and such is his lens. His attempt to rename the lands into Odrzania (Oder River Land) is as inaccurate as it is flawed. But among the most condescending is his attitude to the people who built their lives there. Almost as if in an attempt to strengthen and justify the contrast between his imagined lands of Odrzania (confronted with a made-up “Wiślania”, Vistula River Land – the other part of Poland), he questions the identity of the people of the western lands. Since they come from somewhere else, he claims they essentially identify with nothing, and come from nowhere. This negation (of identity, of place) weirdly carries on in another recent non-fiction offering entitled Niedopolska by Sławomir Sochaj. Its title can be loosely translated as “Not Quite Poland”, a land that’s not Polish enough, and employs a questionable measure that suggests, again, a state where a place does not possess equally the same Polish identity as the other parts of the country. This loose smattering of thoughts purports to use academic ideas, such as postcolonial theory, in order to make sense of the lands that bear so much complexity. It is a land (and a singular one, too) that was colonized, where people are deprived of agency and reliant on mimicry (whatever the author means by it – as none of these terms and theories is ever defined). So, for many, the subject is hot, it is weird, one might even say, oriental. And in both of these adventurous writings, some things could be forgiven if it was not for their attempt at generalizing a subject that does not allow itself to be generalized. So, again, it is Stalin and his pencil. And a space that needs to be harnessed, conquered, enclosed in a single essay. As if its multifaceted character was too disconcerting, as if it had to be stultified and domesticated.

But in many ways, the form attests to its content, it proves how complex and multilayered and convoluted the story of these lands is

This is precisely why Ćwiek-Rogalska’s Ziemie, a book that occupies a borderland of its own kind, by combining ethnographic methods, a scholarly attention to archival sources and contextual storytelling, is such an important addition to the slew of books written on the subject. Because in order to come closer to understanding, the reader does not need the false pretense of absolute truths, but rather the awareness of the impossibility of adjudicating what a single narrative of “Recovered Territories” could be. The story with no common denominator is not easy to tackle and, yes, in Ziemie there are points where the reader might feel overwhelmed with the plethora of details, multiplicity of individuals and testimonies. But in many ways, the form attests to its content, it proves how complex and multilayered and convoluted the story of these lands is and how through listening to a multiplicity of voices one can put into perspective the complex decisions the settlers had to face upon arriving in the “Recovered Lands.”

What some readers might find disconcerting is a certain lack of critical attitude to the sources. The book seems to espouse the attitude that, in the overall chaos of narratives, testimonies are what should keep us afloat. However, when the author allows testimonies to stand on their own, simply certifying their own presence, they are as if placed in the sanctity of the untouchable archive, as if interpretation would do them harm and skew their meanings. This attitude, which reveals the utmost respect for its subjects, stemming from the author’s anthropological methodology, might prove problematic for historians and literary critics. It is a forgivable aspect, however, when we take into account that, within a web of conflicting and disorderly narratives, there needs to be a control group.

The Lands…were they conquered or liberated, were they “recovered”, or were they lost? Here, two answers might ring true despite a paradox inscribed between them. Ziemie, by bringing attention to complexities and multiple narratives that weave the streams of memory surrounding these postwar events and places, brings awareness to the difficulty the story presents. Surfacing these testimonies shows various paths that split off from that experience. Ćwiek-Rogalska, in this detailed look at the long-lasting consequences of the war, arms the reader with a map and points to the movement – to gain, or, in the communist jargon, to recover lands in the west, meant also to lose lands in the east. One does not exist without the other and, vice versa, this story stretches between loss and gain and is crowded with scores of people who had to face both, in differing proportions. The reader emerges with a sense that the story of the “Recovered Territories” is one that belongs in the realm of the ineffable, one that requires constant unraveling, elaboration and clarification. It is a story that escapes its borders before it is even caught within provisional confines.

Agata Tumiłowicz-Mazur is an independent scholar, writer, and translator. She holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from New York University, where she wrote a dissertation on the living link between archive and performance. She is currently researching the material traces of the past in her native Lower Silesia, Poland, and working on her first book. Her writing has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Apofenie, The Theatre Times, and other publications. She loves peonies and the grounding presence of mountains.

1 As quoted in Karolina Ćwiek-Rogalska, Ziemie: Historie odzyskiwania i utraty (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Radio Naukowe, 2024), 66. Translation mine.

2 Ibid. 68