A definitive history of the Soviet dissident movement

Lucy Jeffery’s in-depth review of Benjamin Nathans’ Pulitzer Prize-winning book, To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement (Princeton University Press, 2024), highlights not only the treasure trove of information on the legal texts, court proceedings, and correspondence concerning samizdat writers and smugglers, but also notes that the parallels with Russia today will not be lost on contemporary readers.

As I write this review, CNN is reporting the unveiling of a life-size monument to Joseph Stalin in Moscow’s Taganskaya metro station.1 It is a replica of the statue titled “Gratitude of the People to the Leader and Commander” that supposedly went missing in 1966 during the reconfiguration of the metro. Does this act mark a move away from de-Stalinization towards re-Stalinization? And, if so, to what end? Any consideration of modern-day Russia requires a detailed knowledge of its complex twentieth-century history. This is where Benjamin Nathans’s detailed, richly evidenced, and engaging book To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement can play a prominent role. Readers may fully appreciate how a country’s people who, for several generations, have only known authoritarianism may not balk at such re-Stalinization efforts. As such, the relevance of To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause is not lost on contemporary readers. In its depiction of the struggle of citizens, so called “dissidents”, against the curtailment of fundamental human rights in Soviet Russia, this book draws contextual and circumstantial parallels with the infringement of civil liberties under Vladimir Putin.

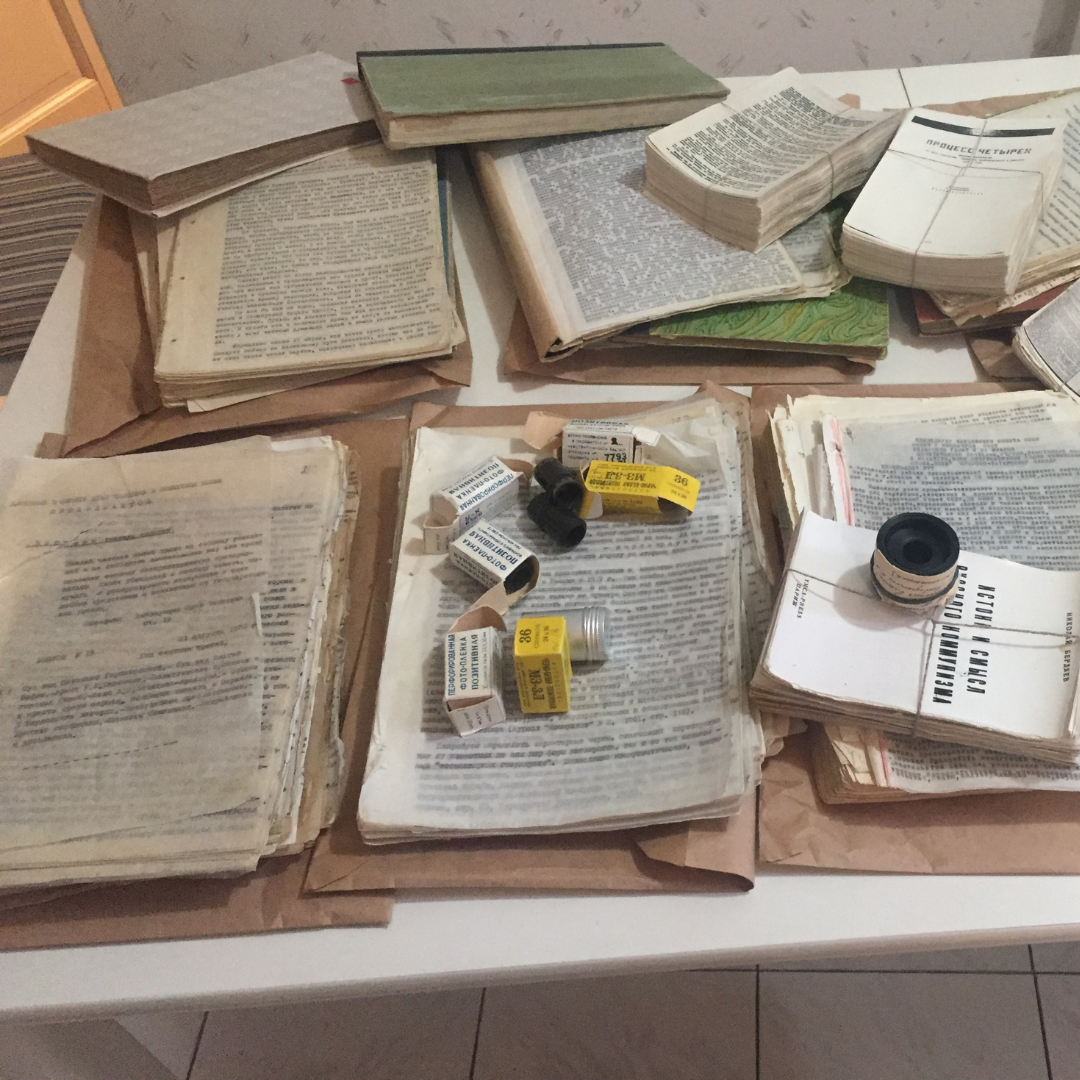

To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause documents the trials and tribulations of those who struggled for freedom in its multitude of forms (inner, outer, social, spiritual, personal, collective) in an environment that was utterly inhospitable towards any pursuit of freedom. Nathans is quick to point out that the term “dissident” is both helpful and potentially misleading. It captures the revolutionary spirit of the group but perhaps misses the more nuanced forms of dissidence to which individual members subscribed, such as inakomysliashchie (people who think differently), pravozashchitniki (rights-defenders), and zakonniki (legalists). At over 800 pages, the size of this book immediately signals that this history of the loosely called “dissident movement” offers detailed insights into the specific forms, methods, and conceptualizations of being a “dissident” in the USSR. Hence, the book outlines the professional and personal lives of the members of the dissident movement. It describes the unauthorized public gatherings (such as the 1968 Red Square demonstration against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia), petitions supporting arrested intellectuals, production and circulation of banned samizdat texts (especially the Chronicle of Current Events journal), challenges to corrupt legal proceedings and sentencings, and the establishment of connections with Western journalists and NGOs such as Amnesty International.

The book is divided into five sections with a Prologue and Epilogue. The sections include three to six chapters, each between approximately 25 and 40 pages. Any book that extends beyond 800 pages, as this one does (if we include front and back matter), poses a challenge for its author to maintain a coherent argument or develop a consistent narrative. Each chapter, therefore, reads more like a discrete essay belonging to a subsection that is, in and of itself, the length of a book. Moreover, Nathans only begins to signpost at page 230, offering the reader a sense of coherency thereafter. There are, after all, many characters, concepts, and scholarly foundations to introduce and develop. The difficulty in keeping so many elements afloat is reflected in the somewhat disjointed discussion on samizdat which takes place across several chapters, risking slight repetition. These, however, are merely “micro-gripes” as the level of scholarship throughout this book is consistently high. In the remainder of this review, therefore, I shall comment on what I believe to be some of the book’s most enlightening sections.

With the exception of maverick dissident Amalrik, Nathans believes that “Soviet dissidents were not born but made, and made with Soviet ingredients.”

Seven chapters deserve special mention as examples of Nathans’s excellence. “Rights Talk” (pp. 129-47) is a sharply written chapter about the law-based strategy used by both dissidents and the Soviet government, especially evident in Article 190 which was used to punish those who disseminated anti-Soviet ideas. In “Chain Reaction” (pp. 147-95) Nathans sets the scene for his analysis of judicial proceedings, outlining the acquittal of Vladimir Bukovsky (defended by the incomparably brave Dina Kaminskaya). He also introduces samizdat as that which “turned reading into an act of transgression” (p. 171). “Will the Dissident Movement Survive?” (pp. 294-316) is an example of Nathans’s ability to combine biography and historiography as he introduces the dissident Andrei Alekseyevich Amalrik, known as the “lone wolf” for his individualism and aversion to collective actions, and discusses Amalrik’s widely circulated 1969 essay Will the Soviet Union Survive until 1984? It is here that Nathans makes his overarching observation clear. With the exception of maverick dissident Amalrik, Nathans believes that “Soviet dissidents were not born but made, and made with Soviet ingredients.” He goes on: “Their making typically began with a stumbling block, an ethical dilemma or cognitive dissonance rather than outright repression, set in their path by the Soviet system, triggering a reevaluation or repurposing of the norms by which that system initially formed them” (p. 294). “Taking the Initiative” (pp. 336-73) exactingly conveys the sense of “informer mania” (p. 344) that suffused the dissident group and documents the lives of Petr Yakir and Viktor Krasin, the self-appointed leaders of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Civil Rights in the USSR (the first civil rights organization in the Soviet world), who, when on trial for the charge of anti-Soviet propaganda (under Article 70), betrayed several fellow dissidents.

“The Fifth Directorate” (pp. 391-432) is the book’s core chapter. It introduces the KGB’s use of psychological warfare (a tactic expanded on in later chapters) where dissidents faced involuntary emigration or forced confinement in psychiatric prisons and hospitals, justified under Nikita Khrushchev’s introduction of profilaktika, which was introduced in 1959 as a means to “nip deviant behavior in the bud, setting errant Soviet citizens on the path to productive and patriotic lives” (p. 402). Finally, “How to Conduct Yourself” (pp. 452-87), the final chapter this review singles out, exposes the crux of dissidents’ spirit: individuals who strove tirelessly for freedom. Here, Nathans expands on Rebecca Reich’s 2022 publication State of Madness: Psychiatry, Literature, and Dissent After Stalin. In their cultivation of an inner freedom, dissidents, Nathans argues, underwent “an abstinence from public life” (p. 461) and were united by “an element of make-believe, a dogged determination to live “as if” against the background of an immovable “as is” (p. 462).

Later, in the Epilogue, Nathans explains how several techniques in the KGB repertoire of dealing with dissidents have come back into use, including involuntary incarceration inside psychiatric institutions.

The book’s title comes from the toast frequently made at dissident gatherings. “To the success of our hopeless cause” encapsulates the bravery amidst adversity among the dissidents who railed against the Soviet machine in all its guises, from its legal articles to its literary censorship. Nathans draws on diaries, memories, personal letters, interviews, and KGB interrogation records to paint a detailed picture of this “hopeless cause”. The inclusion of photos of the dissidents under discussion complements Nathans’s text nicely, providing the reader with a sense of intimacy with the dissidents themselves. Moreover, Nathans’s consultation of materials in archives situated in the US, the UK, Germany, Lithuania, Russia, and Israel is testimony to the thoroughness of his inquiry. Another example of this thoroughness can be seen in the mention of former KGB archivist Vasily Mitrokhin in footnote eleven to chapter fourteen (pp. 707-8). Here, Nathans alights on the remarkable bravery of an individual who, in what can be termed an act of glasnost(transparency), smuggled documents outlining KGB operations to the West to guarantee their accessibility for future generations. In the same footnote, Nathans laments the unlikelihood of full transparency in Russia due to the continued presence of siloviki (enforcers), who once belonged to the KGB, in Putin’s political coterie. Later, in the Epilogue, Nathans explains how several techniques in the KGB repertoire of dealing with dissidents have come back into use, including involuntary incarceration inside psychiatric institutions.

As I hope this review highlights, To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause is a book of great range and depth. Some sections are moving, especially the description of poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya’s suffering at the hands of the Fifth Directorate (pp. 416-18); an example of what Nathans succinctly terms the “pathologizing of dissent” (p. 416) by the Soviet psychiatric establishment. Other sections, such as the description of Fifth Directorate and KGB officer Viktor Orekhov’s sympathies with the dissident movement (p. 492), invoke an element of surprise. Yet, it is the revelatory sections of this book that will make it a foundational text for years to come. In particular, readers are introduced to the man who, according to Nathans, “sparked” (p. 614) the dissident movement: Alexander Volpin. In the book’s initial chapters, Nathans explains how Volpin, a mathematician with a keenness for the logical use of language bolstered by an interest in the linguistic philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, put forward his unique brand of “civil obedience”, using the KGB’s own stick to beat them with. In order to do this, Volpin advocated that arrested dissidents on trial demand accountability by forcing the KGB to respect their own rule of law, namely the Soviet Constitution of December 5, 1936 (the eve of Stalin’s Terror) which guaranteed robust protection of civil liberties (freedom of speech, the press, and assembly). Cleverly and somewhat unexpectedly, Volpin exploited the very system that punished him. Through this performative conformism, Volpin acted “as if the veneer were more than just a veneer, as if the language of law were transparent and binding on both the state and individual citizens” (p. 44) to destabilize Soviet judiciary itself.

Not only does winning the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in General Nonfiction guarantee Nathans’s place in the scholarly canon but it speaks to the book’s readability and relevance in the contemporary political climate. In this review, I tend to agree with Philip Boobbyer’s (author of Conscience, Dissent and Reform in Soviet Russia, 2005) earlier remarks on Nathans’s book in which Boobbyer claims that To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause will become the definitive work on the Soviet dissident movement.2 The book will be useful to scholars working on Soviet history as well as to researchers interested in Nathans’s reading of legal texts, court proceedings, and correspondence concerning samizdat writers and smugglers (like Hélène Peltier, a French smuggler studying at Moscow State University). Indeed, while reading about Nobel laureates like physicist Andrei Sakharov and writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn fosters understanding through recognition, Nathans’s book is perhaps more important for its documentation of the lives and actions of those who risk being relegated to the footnotes of history.

I was left wondering whether the Soviet Union entirely fell or if it lay dormant. Where have the greatest forms of change occurred in post-Soviet Russia?

This book can be read alongside several studies on the topic of Soviet dissidents, from Barbara Martin’s Dissident Histories in the Soviet Union: From De-Stalinization to Perestroika (2021) to Juliane Fürst’s Flowers through Concrete: Explorations in Soviet Hippieland (2020), which I had the pleasure of working on in my capacity as Project Editor at Oxford University Press. Though published in 2008, Stephen Kotkin’s Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse 1970-2000 still complements Nathans’s book, as Kotkin explains how and why the Soviet Union fell. Kotkin’s suggestion that the USSR’s demise was more self-destruction and inability to reform than Western strongarming chimes with Nathans’s argument that: “1991 belongs to a distinctive pattern in Russia’s history, in which seemingly entrenched regimes of various kinds have been hollowed out and made brittle prior to suddenly imploding” (p. 630). This sense of “imploding” or “hollowing out” suggests that the Soviet Union reached a point where it could only fall by its own sword.

Upon finishing Nathans’s book, I was left wondering whether the Soviet Union entirely fell or if it lay dormant. Where have the greatest forms of change occurred in post-Soviet Russia? What sort of regime does Putin preside over today when considered alongside the Stalinist and late-Soviet eras? Though the answers to these questions fall outside the remit of To the Success of Our Helpless Cause, which focuses on the Soviet period, Nathans’s research would provide a solid foundation for any subsequent study on both the similarities and differences between the apolitical dissidents of the Brezhnev era and the politically engaged post-Soviet activists of today.

Lucy Jeffery is Co-Founder of the “Replaying Communism” research project which received AHRC funding in 2023. She has published widely on twentieth-century literature, theatre, and culture. Her monograph, Transdisciplinary Beckett: Visual Arts, Music, and the Creative Process was published in 2021, and she co-edited the “A New Poetics of Space” special issue of Green Letters in 2022. She has also published research on the political context of the mid-twentieth century faced by authors such as Magda Szabó. In 2024 she won the Visegrad Fellowship, and she is currently co-editing the forthcoming collection: Replaying Communism: Trauma and Nostalgia in European Media and Culture.

1 “New Stalin monument in Moscow subway stirs debate,” CNN, May 23, 2025.

2 Philip Boobbyer, “To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement by Benjamin Nathans (review),” Slavonic and East European Review 102, no. 4 (2024): 782-84 (p. 782).