Fraught but exciting: Using fiction to bridge history with memory

Kurt Johnson reviews Cécile Desprairies’s semi-autobiographical novel The Propagandist and Lea Ypi’s Indignity: A Life Reimagined, arguing that while literature can bridge history and memory, it carries an inherent risk: histories vulnerable to erasure are also vulnerable to fabrication.

Over two days in the sweltering July of 1942, French police, at the behest of the occupying Germans, rounded up 13,000 Jews, including women and children. Around 7000 were taken to the Vélodrome d’Hiver in Paris’s fifteenth arrondissement where they stayed for five days before being sent onwards to their ultimate terminus: Auschwitz. Just 100 would outlive the war.

Only one photograph of the roundup has survived. The frame is askew, suggesting covert capture, it shows a line of buses parked outside, implying human cargo. Having already postponed from Bastille Day fearing riots, the occupiers were wary about the reaction such an operation might trigger and forbade any media coverage. The photo was discovered by Holocaust survivor Serge Klarsfeld in the Paris-Midi newspaper archives of the Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris in 1990. The photographer’s identity remains a mystery.

According to one paper, the Roundup has become a “national obsession” in France, indicating complicity in the Holocaust, part of a larger conversation about collaboration and guilt. Intensive research has cemented the details beyond doubt, yet the lack of photographic evidence prevails, a “visual void” that hints at a worrying question: how often is history incomplete? Of course, this is impossible to answer, we simply don’t know what we don’t know.

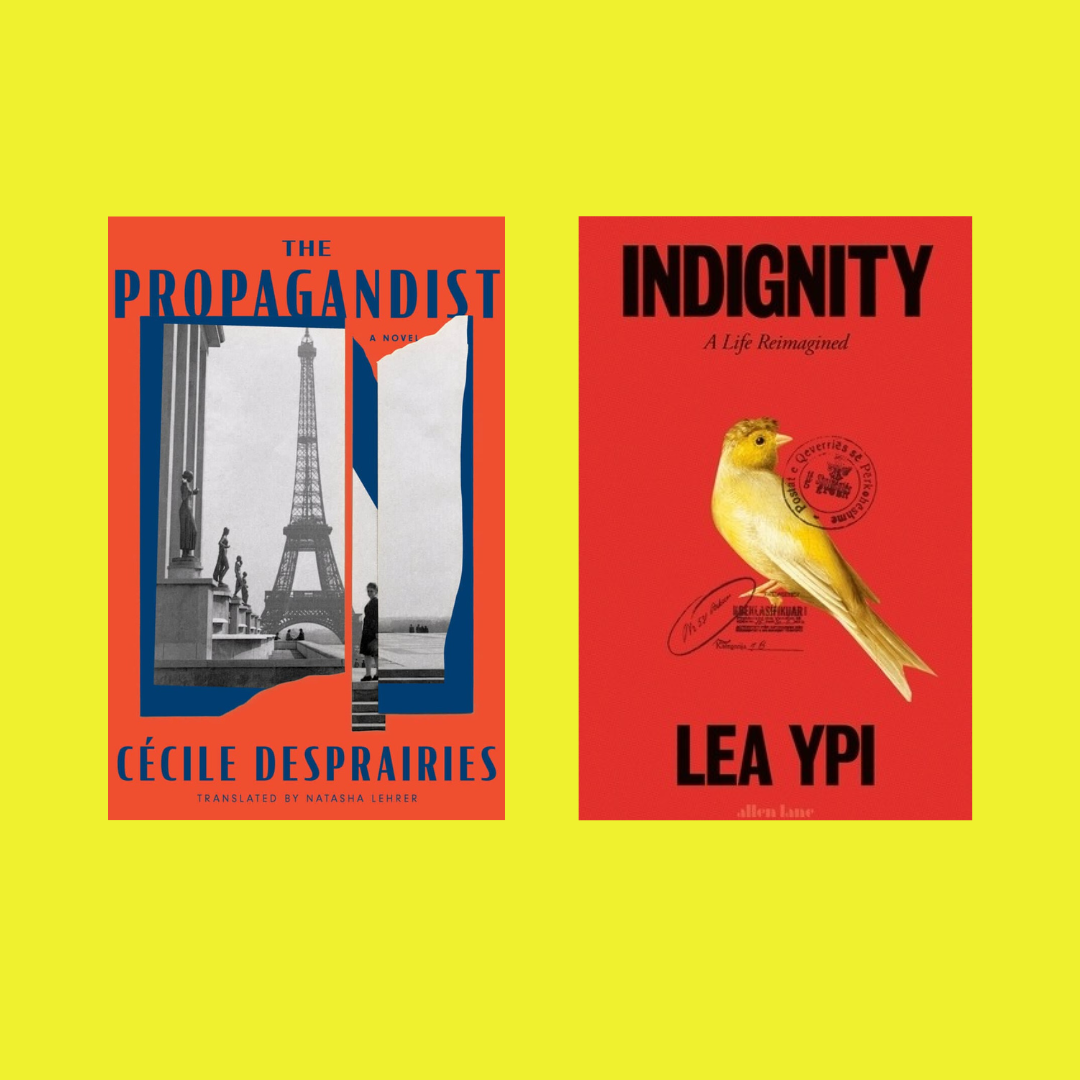

Cécile Desprairies’s award winning semi-autobiographical novel The Propagandist and Lea Ypi’s recent Indignity: A Life Reimagined rebuke convention by using fiction to reanimate and complete suppressed partial histories.

History, the authoritative account of the past, may have other limitations too. A strict (and necessary) adherence to objectivity is often incompatible with capturing the essence of a past subjectively experienced. For example, we know from history that the velodrome’s glass roof, designed for winter competition, trapped the heat inside, while the insulation ducts had been plugged to prevent escape. We also know the intricate plans made no provisions for food or water. These facts may help someone today reconstruct the nightmare within but to truly connect to the memory one must venture beyond mere facts: either into eyewitness accounts (permissible but often supplementary in “serious” history) or imagination (a far more dubious inclusion according to the constraints of history).

Cécile Desprairies’s award winning semi-autobiographical novel The Propagandist (New Vessel Press, 2024) and Lea Ypi’s recent Indignity: A Life Reimagined (Allen Lane, 2025) rebuke convention by using fiction to reanimate and complete suppressed partial histories. They are not the first to do so. WG Sebald made a career from similar syntheses. Yet, both Desprairies and Ypi are using the form to reflect on their own family’s entanglement with suppressed histories, silence and fascism.

At first, permission to invent feels like liberation from history’s stuffy constraints. Soon though, the risks present themselves. Taking the Vel d’Hiv photograph’s minor but indicative example in The Propagandist, Desprairies anecdotalises the photo’s capture. She attributes it not to some anonymous gumshoe, but “Uncle Gaston”, a successful editor of the collaborationist daily Paris-Soir who, according to the story, scrambled onto an apartment block’s roof to take the shot.

what is invention and what is the author using the veil of fiction to say out loud?

This reflects the author’s bind: the more authentic the fiction, the more perilous alloying it with history can become, a sort of historical “uncanny valley” where high fidelity imitation can be more disconcerting than pure fakery, threatening to breach the form and contaminate the original record. “Uncle Gaston” has a real-life doppelganger: Gaston Bonheur, a journalist who worked at the Paris-Soir (not quite Paris-Midi) and was hired by the same real-life Jewish editor as the “Uncle”. Both lived to around the same age, dying only in 1980. I could find no evidence of Bonheur harbouring fascist sympathies, although he certainly worked for what became a collaborative rag amidst the occupation. One wonders what his descendants may feel when reading The Propagandist.

While this small anecdote is buried within the novel’s wide sweep, it is indicative. We are left to wonder: what is invention and what is the author using the veil of fiction to say out loud? Given the depth of knowledge that Desprairies brought to this, her first novel, we can assume accidental similarities are unlikely. Before The Propagandist, Desprairies had written five works of non-fiction, all on the Occupation, dealing with subjects ranging from legislation still on the books to the influence on Paris’s urban landscape to decoding propaganda photography. If one were to draw these threads together into a single career-spanning conceit it would be this: the Occupation continues to influence French society today, hiding in plain sight.

Leaving aside the messiness of mixing fact and fiction, as a pure novel The Propagandist is excellent. It centres on Lucie, based on Desprairies own mother. In The Propagandist Lucie is the leader of “the gynaeceum”: an all-women group that meet each morning in her apartment the moment her husband leaves for work. They strip to their underwear and begin a highly ritualised and heavily coded act of remembering. Much of it is opaque to Lucie’s young daughter, Coline. When she finds Lucie’s identity card bearing a different surname, she realises something beyond the normally inscrutable lives of adults is happening.

From here Coline unveils this secret past. Lucie had been married before and had another life during the Occupation when she produced Nazi propaganda for the Germans that was so effective she became known as the “Leni Riefenstahl of Posters”. Her first marriage was to Friedrich, an Alsatian biologist dedicated to advancing the new “science” of eugenics. Both Lucie and Friedrich were bona fide Nazis, devoted to realising the Thousand Year Reich. Their relationship was thoroughly ideological, from their visceral antisemitism to exchanging literature on racial science. Yet they were happy and in love. Desprairies rejects casting them as automatons though: Lucie’s sacrilege lies in professional ambition, a rebuke to the dirndled, platted hausfrau.

For Lucie and her cohort, opportunities materialised as from a vacuum, leaving unacknowledged the promising career suddenly truncated, the family heirloom pawned cheap, the expensive apartment hastily vacated.

The Propagandist includes a constellation of collaborators that socially orbit Lucie. All are fully realised, and complex characters: Lucie’s great uncle Räphael, for example, is a homosexual enamoured with fascist pageantry, who threw wild parties despite wartime deprivations. All experienced a sudden surge of career opportunity when Jews began to vanish – opening access to high society.

In 2010, Desprairies wrote Sous l’œil de l’occupant: La France vue par l’Allemagne 1940–1944, a compilation of propaganda photos: France from the occupiers’ perspective. She paid particular attention to what was missing from the photos, something she revisits here. For Lucie and her cohort, opportunities materialised as from a vacuum, leaving unacknowledged the promising career suddenly truncated, the family heirloom pawned cheap, the expensive apartment hastily vacated. We are introduced to remembering’s ulterior side: the conscious act of forgetting as collaborators ignore the origins of these sudden opportunities. Instead, they work hard, they say, and deserve their reward. The only honest (and shocking) instance of pillaging on the personal level occurs during the roundup. Lucie’s mother takes a gold watch from a Jew through the “enclosure”, in exchange for a glass of water. The water is never given.

On occasion, Desprairies is clearly using this novel to venture a broader comment gleaned from research. As a child, Lucie was a brilliant student, awarded a scholarship to an elite Parisian high school. There she had been surrounded by rich Jewish students who mocked her rural Burgundy accent. This class resentment metastasised into racial hatred, affirming August Bebel’s adage, that antisemitism is the “socialism of fools”. Such was the nature of much French (and perhaps European) antisemitism.

Desprairies also hints at the conspiracy of silence amongst collaborators, something she must have contended with in writing non-fiction. As Liberation draws near, Friedrich dies under mysterious circumstances. Lucie meets with the other collaborators, where she orders them to go to ground, to be disciplined and say nothing. As other collaborators are jailed and beaten, their heads shaved, Lucie’s clique launder their identities to emerge pristine, humbled yet privately outraged at history’s deceit. Justice was neither measured nor fair. Later the gynaeceum meets daily to secretly remember their former glory. Lucie remarries and soon, Coline is born, and thwarts any social reckoning with her past.

In a break with literary convention, Nazi sympathisers are afforded a sympathy of their own. Lucie is ruthless, heartless and reprehensible but also tragic. Her second husband realises he will always play second fiddle to Friedrich, allowing their son to be named Frédéric. The rest of her life is spent in a nostalgic shadowland, that further dims as each gynaeceum member dies, long after Nazism’s victims, it must be noted.

The Propagandist’s form is as authentic as its world. Coline, who in adulthood became a historian like the author, includes tangential facts about the collaborators, many of whom vanish quietly from the narrative. All this gives the plotting the “ragged” shape of true historical research, instead of the smooth narrative of a traditional novel, which flows irrevocably toward a finale. This raggedness implies an incomplete record limited by trauma and deliberate suppression.

At the same time The Propagandist’s characterisation of collective memory is vivid and living. The gynaeceum are archetypal “memory carriers”. Despite their absolute public silence, privately they perpetuate memories through stories and jokes that have long exhausted their humour. For almost all members, the years hence have been empty, they are sustained through remembering: the past a foreign country from which they are political exiles. Forgetting is part of memory too: the gynaeceum members never discuss the Holocaust, about which Coline only ever learns in school.

The prodigal granddaughter returns to Tirana after fleeing the economic chaos post-collapse.

Public forgetting and secret remembering are also central to Lea Ypi’s Indignity. Another work of semi-fiction that pivots on a photograph. This time the image is of the author’s grandparents, taken on their 1941 honeymoon reclining on sunchairs at an Italian alpine resort in the Dolomites. Both look to be smiling but her grandfather might be wincing. Even photography is ambiguous. Leman, Ypi’s grandmother, told her this was the happiest time in her life. The author discovered the photo after it was posted online where it caused a minor uproar. Commenters took umbrage with a bourgeois display of leisure during a world war. Ypi fretted not about the ensuing trolling but the official record. The trolls conjured up a woman unrecognisable to the author.

Indignity expands on Ypi’s first book, Free, a brilliant but more traditional memoir about the communist collapse and aftermath in Albania. In it, Leman was clearly from another world, out-of-step with the isolationist, Stalinist state. Sophisticated and well-read she spoke several languages, including French like a native. Like the gynaeceum, she engaged in private social remembering about a secret pre-communist past using a coded language to confuse the young author lest she blab in school.

In Indignity, Ypi is granted access to declassified Sigurumi archives. The prodigal granddaughter returns to Tirana after fleeing the economic chaos post-collapse. Her reaction is typically absolute: “Everything has changed,” she tells a taxi driver. He retorts that, while new trees have been planted beside the road, in truth, everything is still the same. This is memory: subjective, contested, always under revision.

The Sigurumi archives are as grey, fluorescently lit and nicotine stained as one would expect. The Albanian state decided to declassify files now that a generation of informants had died off. That Ypi is there echoes academic findings about traumatic memory – it spans generations.

“When I mention this to historians, they smile. It’s the best kept secret about archives, they say: It’s more about what you don’t find, rather than what you do.”

She is assigned an old laptop and, under the watchful gaze of vigilant if apathetic bureaucrats, confronts the raw material from which history is made: eight hundred hand-annotated, scanned, yellowed pages of informant reports. She discovers their contents are often inaccurate, incomplete and contradictory. Basic details like dates and names are wrong – a final upset upends the entire enterprise. Ypi also suspects that Leman was aware of informants in her midst and dissimulated, further muddying the record. Despite the noise, Ypi locates the vague simulation of Leman.

The first realisation of Indignity comes from the sections of pure non-fiction. No matter the detail or accuracy of source material, history demands more interpretation than most within the discipline would concede. History’s hallowed objectivity is an illusion. Ypi discovers this directly: “When I mention this to historians, they smile. It’s the best kept secret about archives, they say: It’s more about what you don’t find, rather than what you do.”

This forms the basis of her second conceit, which takes much of Indignity to realise. Ypi is unable to locate Leman in history not just because history is incomplete but because memory and history have incompatible architectures. History is the official record of the past; it refines details and develops new narratives and arguments. History declines to comment on the present (although historians might). Memory, on the other hand, is the recollection of experience in the present, both individually and socially through stories, conversation and media. Where history is iterative, memory is fluid. History is built on objective facts while memory on subjective experience. In other words, Ypi will never find her grandmother in the archives because she is searching for a memory in a raw historical record.

While Desprairies never attempted to reconcile memory with history, separating the gynaeceum from the historical events, Ypi is endlessly frustrated, triggering the urge to “reimagine”, to connect history and memory.

Unlike The Propagandist’s thorough integration of historical matter with fiction, history in Indignity is used more as scaffolding to tell Leman’s story, which spans one rupture after another: the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, population redistribution between Greece and Turkey, the family’s move to Albania, the Second World War and Albania’s communist coup. Each is heralded as the birth of a new epoch and carries an implied threat to any existing history, a relic of the old order.

Early on, Indignity lacks the authenticity of The Propagandist. The levity and snappy dialogue that worked with Free’s surreality of communism’s end, feels too slick to be authentic. In truth, there are limits not just to history but to imagination too – the world of a rich family during interwar Salonika within the Ottoman Empire may be too remote from Ypi’s lived experience to reconjure, a reason why so much historical fiction comes off as kitsch.

The closer the story gets to Ypi’s world the more authentic Indignity becomes. Still Ypi was left with the fraught task of writing family members and historical figures she never met, including, boldly, the young Enver Hoxha, written as a playboy and dilettante. Her great uncle, Xhafer Ypi, the head of state when the King fled during Italian occupation, was faced with the real-life impossible decision of surrendering Albanian independence to the Italian fascist state. This was a fait accompli given Italian troops were already occupying the country. Resistance would have been a bloody and empty symbol. Yet this would later be characterised by the communists as a national betrayal, with Xhafer and the Ypi family maligned by the regime, the source of the young author’s suspicion in Free, and her quest in Indignity.

Ypi realises that a precarious historical record is not the solely the product of historical materialist states.

In its treatment of collaboration, Indignity is far milder than The Propagandist and the intent is not to confront any familial demons. If anything, Ypi avoids characterising any of her family as sympathisers, an interesting framing given that jilted former elites were excellent contenders. The only Nazi is conveniently a German businessman.

Toward the end of Indignity, Ypi visits Thessaloniki in the hope of discovering information about her grandmother’s childhood there. She gives a talk at a university built on top of a Jewish Cemetery that was systematically demolished by the occupying Nazis. Despite attempts to memorialise the site, almost none of the students know of its existence. Even so what remains is routinely vandalised by neo-Nazis. Ypi realises that a precarious historical record is not the solely the product of historical materialist states. If anything, the Albanian communist regime was prescriptive but intentional in its memorialising while history in capitalist Greece seems irrelevant to any university students not studying history.

In the end, both works of semi-fiction push beyond the limits of history, specifically its incompleteness and incompatibility with living memory. Such efforts are at once ambitious, impressive, fraught and, in yearning to reconcile knowledge with experience, impossible to achieve. This does not preclude their literary value. Indeed, they plot space for a new genre: synthetic memory. Akin to prosthetic memory – where events never experienced can be absorbed as memory via media – synthetic memory would be memory constructed from history and imagination. Literature may one day prove a successful bridge between history and memory. Yet such a genre must acknowledge the inherent risks: any history vulnerable to erasure is similarly vulnerable to fabrication. The same imaginative license that completes a suppressed past can also distort it—transforming an anonymous photographer into “Uncle Gaston,” or a grandmother’s ambiguous smile into unambiguous meaning.

Kurt Johnson is an independent memory scholar, literary journalist and book critic. He has written one book The Red Wake which treats memory in the Soviet Union. He writes on climate, memory and tech. His portfolio is here.