Left-wing agency and the question of social morality in Russia

Veronika Pfeilschifter provides an in-depth reflection on Ilya Budraitskis’ Dissidents Among Dissidents: Ideology, Politics and the Left in Post-Soviet Russia (Verso Books, 2022), elaborating on how Budraitskis’ study can be positioned in larger debates regarding dissidents and the philosophical underpinnings of political violence.

In his essay collection Dissidents Among Dissidents: Ideology, Politics and the Left in Post-Soviet Russia, scholar and socialist intellectual Ilya Budraitskis offers an important and carefully researched analysis of Russia’s political and cultural sphere with a particular focus on the embeddedness of left-wing actors, thought, and practises up to the year 2020. While an in-depth examination of Russia’s Soviet and, to some extent, post-Soviet left is the main focus and most insightful part of the book, Budraitskis’s reflections on Russia’s international relations and domestic cultural politics help position the left within a broader historical and theoretical perspective. Overall, this book is an interdisciplinary undertaking that juxtaposes political and intellectual history with political theory.

The essay collection consists of three main parts: Fantasy Worlds of Power (Part I), Cultural Politics in the Putin Era (Part II), and Soviet Inheritance and the Left (Part III).

Part I (Fantasy Worlds of Power) is dedicated to a theoretical political analysis of hegemonic Russian and Western geopolitical imaginaries and the role of intellectuals in the production of “Cold War” binary political stereotypes during and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is primarily based on literary sources written by historians, political scientists, and theorists. Budraitskis argues that taking “a third position” (p. 21) – outside of “bad existing socialism” associated with the Soviet Union and the “good alternative” associated with “the West” – “seemed impossible” (p. 21) during and in the aftermath of the Cold War and that “the brutal binary structure of the conflict between East and West was reproduced even unconsciously” (p. 21).

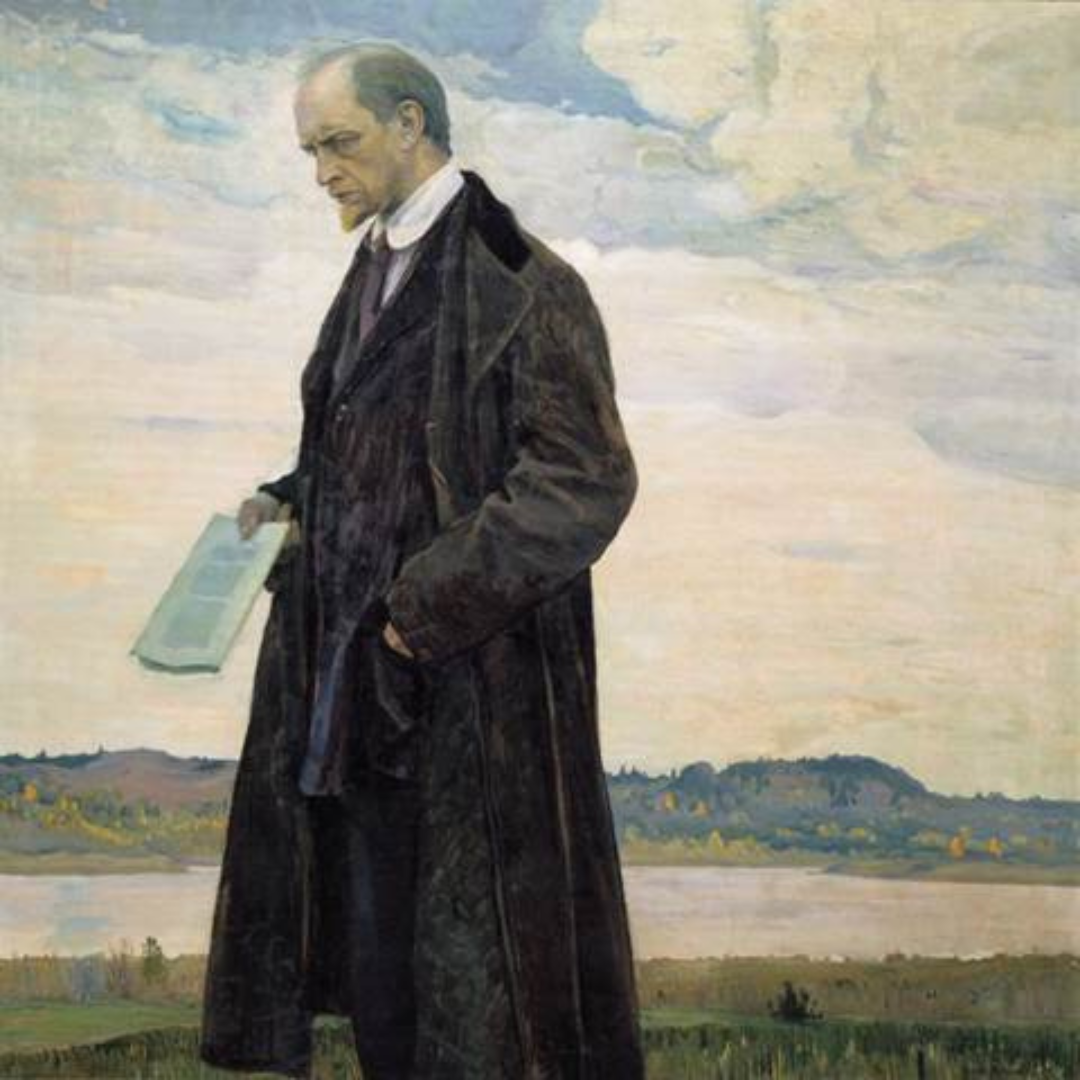

Part II (Cultural Politics in the Putin Era) is a reflection on broader developments in Russia’s post-1991 cultural politics. It offers a nuanced and deeply interesting elaboration on the moral philosophy of émigré thinker Ivan Ilyin (1883–1954), whose political thought has exerted great influence on some of Russia’s current political elite, including, for instance, human rights commissioner Tatyana Moskalkova and Russian president Vladimir Putin. I will revisit Ilyin’s philosophy in greater detail later in this review.

In Part III (Soviet Inheritance and the Left), by presenting original accounts of and interviews with left-wing activists, organizers, intellectuals, and politicians, Budraitskis convincingly argues that left-wing agency existed in Russia’s Soviet society as an alternative to the hegemonic Soviet state apparatus.

In the following, I provide a more in-depth reflection on Dissidents Among Dissidents by focusing on Parts II and III. First, I elaborate on how Budraitskis’ book can be positioned in larger debates on the moral dimensions of Soviet history and the issue of socialism as a political idea. Then, I examine the aspect of ruptures and continuity among the Russian left. Afterwards, I elaborate on the moral philosophy of Ivan Ilyin and his justification of political violence. Finally, I sum up my review by highlighting the book’s strengths and pointing out gaps that could be addressed in future research.

Socialism as a remaining “moral problem” [1]

Throughout his book, Budraitskis illustrates that left-wing ideologies and practices are far from dismissible as futureless. In fact, the book reads as a hopeful outlook – hope understood in a Blochian sense as a commitment towards the future,[2] not as a form of optimism – on a renewal of the left in Russia. This corresponds with the author’s understanding of history which concludes that the Soviet past cannot be cast off easily: “[the] [p]roposed method for exorcising the spirit of former Soviet socialism – de-communization and lustration – solve[s] only part of the problem. The spectre of communism will come to the rescue of the [Russian] government every time it needs to explain away its own mistakes or crimes” (p. 86).

By depicting the various groups and programmes of left-wing dissidents during the Soviet Union both briefly and in a more generalised manner since its collapse in 1991, the book counters a reading of a “fatalistic representation of the choices and the impossibility of any third position” (p. 26). Budraitskis is a pioneer in systematically analysing left-wing dissidence in the Soviet Union, especially with a focus on the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR). The bulk of literature on Soviet dissidence (notably, Horvath 2005 and Martin 2019) has had little to no focus on marginal left-wing subjects.

Such a reading is both provocative and productive as it indicates that although left-wing dissidence, along with other ideological dissidence in the Soviet Union, was mostly punished harshly, some, at times small and very narrow, but still important, space for left-wing agency remained.

The book’s title, Dissidents Among Dissidents, can be read twofold: as an expansion of reductionist depictions of the notion of dissidence and as a theoretical devotion towards neo-Marxist epistemology. Budraitskis argues that the dissident community was more heterogeneous than has been presented in historiographies which focus on the liberal and human rights groups and movements (whose roles remain of historical and political significance). The phrase ‘dissidence among dissidents’ can be traced back to Mikhail Molostvov, one of the former members of the Leningrad Underground, a socialist underground group founded at Leningrad State University in 1956 that spoke out against Stalinism as well as Trotskyism.

The title thus challenges, as Budraitskis himself formulates it, “the false and widespread picture of a confrontation between a totalitarian government and a small handful of freedom-loving individuals and advocates” for a view that sees “Soviet society as a space of conflicts, discussions, and unrealised political alternatives” (p. 166). Such a reading is both provocative and productive as it indicates that although left-wing dissidence, along with other ideological dissidence in the Soviet Union, was mostly punished harshly, some, at times small and very narrow, but still important, space for left-wing agency remained. This socio-political space comparatively widened in the aftermath of Stalinism (after 1953). Before this time, drastic repression persisted. For example, the members of the Communist Party of Youth, which was founded by three ninth-grade high school students (aged 15 and 16) and had the goal of building a communist community, received lengthy prison sentences once they were discovered by the Soviet authorities in 1949.

On the other hand, the reference to Molostvov might underline Budraitskis’s own epistemological and theoretical position as a Neo-Marxist convinced that “a genuine alternative to the current state of affairs in Russia can only come from a left and anti-capitalist perspective” (p. 1). This is illustrated, for instance, in a quote from Molostvov’s lost work (titled ‘My Phenomenology’) written in the 1970s, which Budraitskis included in the book: ‘People ask me “Are you still a Marxist?” “I will remain so”, I answer them, “for as long as I retain my sense of humour”’. Molostvov’s own biography factors in ambivalently here: while serving a seven-year sentence in Dubravalag, the Gulag labour camp for political prisoners (based in the Russian republic of Mordovia), Molostvov took part “in various socialist circles that formed among the prisoners”. He later remained “faithful to his Marxist convictions” (p. 125) for many years after his release.

Multiple ruptures and continuity within the Russian left

Russia’s left, as with all other left-wing groups and movements around the globe, has experienced multiple ruptures and rapprochements related to multiple lines of convergence and divergence. As Budraitskis concludes, “left-wing politics never really reinvents itself anew, but critically evaluates and adapts the organisational praxis, activist style and language of the previous generation” (p. 169). During the existence of the Soviet Union, one major line of conflict among various left-wing dissidents was over the kind of political position to adopt in opposition to the Soviet system. The responses included attempts to radically oppose the Soviet system; to aim for gradual, more externally driven reforms; or to partially subvert the Soviet system from within. Besides diverging attitudes towards the Soviet system, splits also had other causes: sometimes they were purely pragmatic, for example, due to geographical distance (between, e.g., Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the regions); other times they were related to positionality, for example, a split between poets and politicians was described with regards to the aftermath of the Mayakovsky readings (pp. 116–119), which were unofficial poetry readings held in the 1950s and 1960s around the Mayakovsky Square. While Budraitskis offers a wide range of programmatic illustrations, a more pronounced form of ideology critique is lacking. This could have, for instance, included an evaluation of the analysed leftist practices in terms of their moral characteristics.

Regarding the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Budraitskis describes the subsequent splits among the Russian post-Soviet left between “popular (anti-market, statist) Stalinism and democratic socialism; nostalgic idealisation of the USSR and criticism of it” (p. 169). Similarly, another line of distinction took shape regarding what to make of Russia’s imperialism and how to position oneself towards the consolidating multipolar world order. While a considerable part of the left (for example, the Stalinist, red-brown Bolshevik and some of the communists) opposed Russia’s capitalism but enthusiastically supported Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, falsely interpreting it as a “precedent for a worker’s revolt against the reactionary regime in Kiev” (p. 182), another part (for example, the anarchist, feminist, socialist, social democratic, eco-left) has been unambiguously outspoken against Russia’s imperialist aggression in Ukraine.

The immorality of violent force

Since Budraitskis’s book was finalised before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the development of the Russian left, which, in many regards, now functions transnationally, could not be documented. While some leftists continue to support Russia’s full-scale invasion as an alleged “anti-imperialist” or even “progressive” move, many war-opposing leftists went into exile. In addition, those who have spoken out against the war in Russia have faced punishment, arrest, and, often, lengthy imprisonment. Famous among these is, for instance, Russian sociology professor Boris Kagarlitsky, who was sentenced to five years of prison due to his anti-war statements following the 2022 full-scale invasion. Kagarlitsky also has a mention in Dissidents Among Dissidents: in 1977, he was a founding member of the Young Socialists at Moscow State University, who saw themselves as “heirs to socialist groups of the Thaw” (p. 162). He was also an editor of the underground publication Left Turn before being imprisoned for “anti-Soviet” activities under General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Leonid Brezhnev (1960–1982) in 1982.

Ilyn does not regard the state as “an instrument of progress”. According to him, “the state does not foster the new man, but instead sustains the old one, a warrior with his historical mission and affiliation”.

With regards to the (im)morality of violence, in-depth reflection on hegemonic political practices among Russia’s elites and law enforcement is particularly insightful. Here, Budraitskis proposes a reading of the moral philosophy of Ivan Ilyin (1883–1954), to whom Russian president Vladimir Putin has frequently referred in official statements both before and since 2022, for example, at the annexation ceremony for the Ukrainian regions Zaporozhye and Kherson.[3] In his book Resistance to Evil by Force, which was published in 1925, Ilyn proposes an “effective unity” of the spiritual and the political which legitimises the “constant use of force, torture and executions” (p. 65). Ilyn does not regard the state as “an instrument of progress” (p. 73). According to him, “the state does not foster the new man, but instead sustains the old one, a warrior with his historical mission and affiliation” (p. 73). Through this kind of warrior morality, unity of the state and society could allegedly be revived. Budraitskis extrapolates that, according to Ilyn, such a political-spiritual being could also commit violence and injustices – not out of desire but out of necessity. This philosophical interpretation remains relevant in contextualising Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Conclusion

Budraitskis’ essay collection should be of great interest to students and scholars of Russian politics, political ideologies, the history of the left, and the contemporary left in the societies of the former Soviet Union and beyond. In addition, the references to the primary sources of Russian left-wing writers and theorists enable readers to explore beyond Budraitskis’s account. The essay collection requires a certain pre-existing knowledge of Russian politics and the Soviet Union to fully grasp its contents. Thus, readers who have only a vague idea about Russian politics – particularly the left – may have to make an effort to navigate the essay collection. While Parts I and II are very well written, they at times contain generalising tendencies and remain ambivalent with regard to what is factual description and what is the author’s evaluation. A clearer disentanglement between position and description would have been desirable here. The author’s account of leftist dissidents during the Soviet Union and after its collapse in 1991 (Part III) is the most well-presented part of the book.

Budraitskis convincingly demonstrates the value of widening the category of dissidence and including lesser known and less visible expressions of dissidence, resistance and subversion in Soviet Russia. The approach to dissidence carries significant normative implications, and Budratiskis has made a provocative intervention that moves beyond the more traditional liberal and human rights opposition.

Two years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Dissidents Among Dissidents remains a useful source of knowledge for anyone interested in left-wing political projects.

The most recent developments of the post-Soviet left have received only brief attention in Budraitskis’s book. In the future, it will be interesting to see how ongoing research on the Russian diaspora’s and Russian migrants’ critical engagement (notably, Krawatzek/Sasse 2024; Darieva/Golova 2023) becomes tied into the post-2022 history of the Russian left . For an analysis of the further development of the Russian left, both domestically and transnationally, it would be valuable to consider more in-depth the feminist left (which is very briefly mentioned on two pages: 183 and 185) as well as the LGBTQ+ movement and the eco-left. Disappointingly, the role of women among dissidents has, apart from an outline of Lyudmila Alexeyeva, received no specific mention throughout this book. Therefore, further research is needed to examine, on the one hand, the role of female progressive dissidents in Soviet Russia, and on the other, the complex roles of left-wing (both pro- and anti-war) women in the context of Russia’s war against Ukraine. A reflection on these subjectivities could be embedded in an in-depth analysis on the imperial and colonial dimension of Russian politics.

Two years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Dissidents Among Dissidents remains a useful source of knowledge for anyone interested in left-wing political projects. It will be exciting to see additional histories be written on left-wing dissidence in the societies of the former Soviet Union. By exploring specific marginalised groups overlooked by mainstream analysis, they could provide valuable critical insights.

Veronika Pfeilschifter is a social scientist and doctoral researcher at the Institute for Caucasus Studies at Friedrich Schiller University Jena and at the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) Berlin. Her doctoral project, preliminarily entitled “Ideology, Concepts, and Emotions: Taking Stock of the New Left in the South Caucasus”, examines left-wing subjects in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, in particular, from the early 2000s until today.

1 This is an adaption of the monograph title ‘Bolshevism as a moral problem’, written by Hungarian Marxist Georg B. Lukács in 1977.

2 Ernst Bloch, The principle of hope (Vols. 1-3), 1954, 1955, 1959; Suhrkamp.

3 Putin quoted Ilyn here with the words, “If I think that Russia is my Motherland, that means that I love in Russian, contemplate and think, sing and speak in Russian; that I believe in the spiritual strength of the Russian people and embrace its historic fate with my instinct and will. Its spirit is my spirit; its fate is my fate; its suffering is my sorrow; and its prosperity is my joy.”