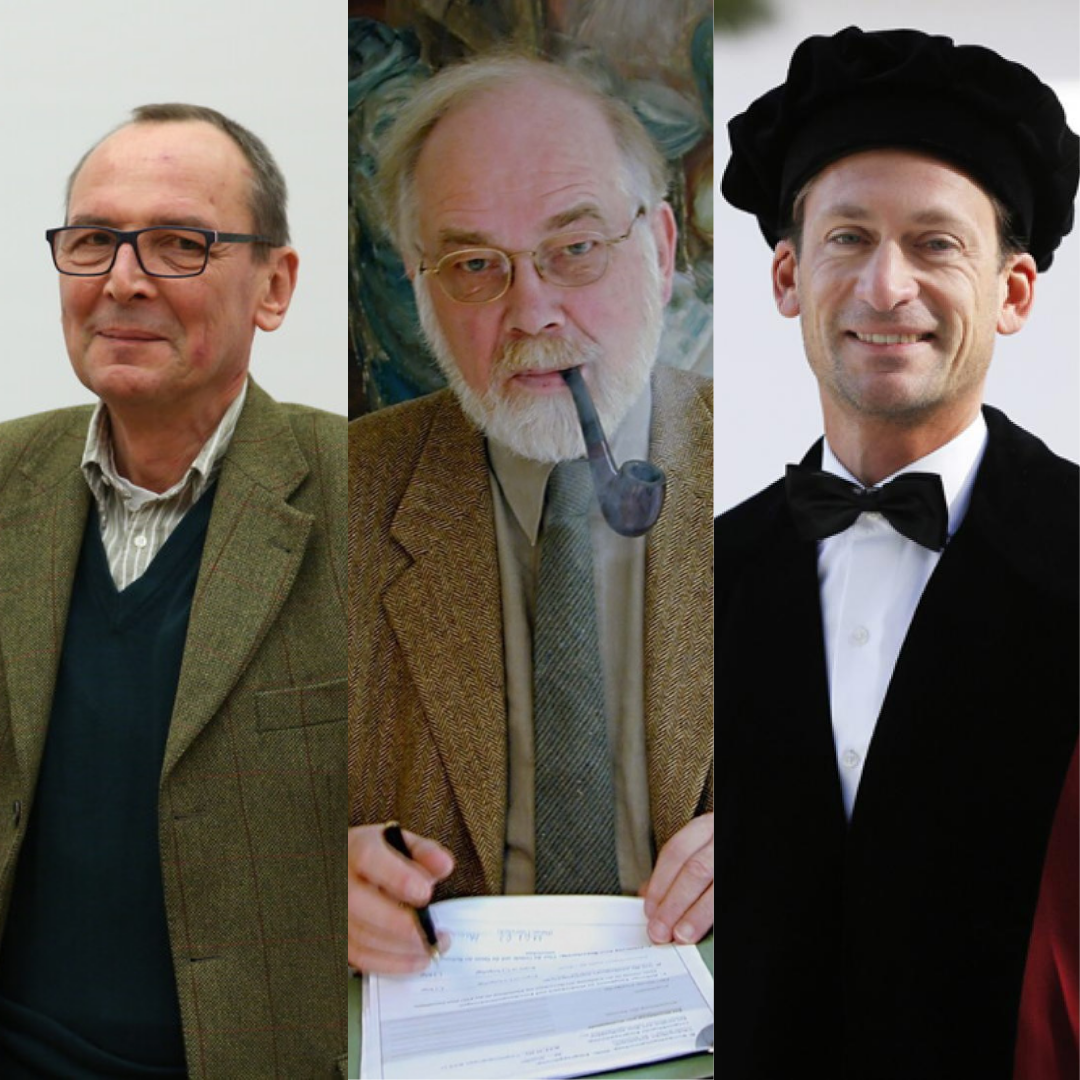

My deceased masters: Portrait of three European historians

To Camilo Erlichman

Ferenc Laczó remembers his mentors Włodzimierz Borodziej, Lutz Niethammer, and Mathieu Segers, historians of Europe’s recent past.

It was the tragic passing of three of my mentors within just a few years that made me realize that I must have become a middle-aged historian.

I am speaking of precisely those three historians who had the greatest influence on my thinking and my understanding of history since the defense of my doctorate back in 2011: the Polish historian Włodzimierz Borodziej (1956–2021); the German Lutz Niethammer (1939–2025); and the Dutch Mathieu Segers (1976–2023).

What follows is my attempt to paint a subjective portrait of them and offer some reflection on their inspiring personalities, through which I may perhaps be able to develop a few insights into Europe’s recent past too.

*

Włodzimierz Borodziej was above all a historian of diplomacy, war, and social history. From 2010 to 2015, he was the deputy director of my institute in Jena, the Imre Kertész Kolleg, thus my immediate superior. He grew up largely in Austria and Germany in a Polish family and spoke German with the most beautiful—Viennese—accent. At the same time, he was unmistakably Varsovian. Indeed, he was a Warsaw Pole and a Warsaw Jew, although he hid the latter (I must admit I learned of it only after his death). This was all the more remarkable because Borodziej was considered something of a star historian in Germany; he was perhaps the most reputed Polish historian just when Poland emerged as one of Germany’s key partners.

I came to know him as piercingly intelligent, unusually reserved, and endowed with tremendous diplomatic skills, yet also someone capable of making quick and sharp judgments. With two or three comments—often seemingly simple, but incredibly apt—he could regularly prompt leading scholars to fundamentally rethink their major studies. He often surprised me during coffee breaks or in the hallway with his clipped remarks. Several times it took me years to realize how keenly he had understood something—and how little I had grasped what he perceived more deeply, even from afar. Perhaps it was this well-cultivated distance that gave his thinking its exceptional edge.

Borodziej was deeply concerned with basic issues such as the provisioning of civilian populations during wartime.

Borodziej was, in any case, the most effective teacher I ever had, though sadly I was never a good student of his, nor were we ever particularly close. I praise him not because of our closeness but because he was a person and thinker of great stature, something even his sworn opponents and rivals (and there were visibly some) had to acknowledge.

Among much else, he wrote a courageous (today we would probably say demythologizing) book on the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, a very thorough overview of twentieth-century Polish history in the German language, and, together with Maciej Górny, a comprehensive history of the First World War in Eastern Europe—a subject of immense significance and yet, in many respects, much neglected. While in Jena, he acted as one of two chief editors of a series of four handbooks on Central and Eastern Europe in the twentieth century.

Borodziej was deeply concerned with basic issues such as the provisioning of civilian populations during wartime. I vividly recall a conference where he—uncharacteristically—snapped at a critic who questioned the importance of discussing such matters in detail: “Why is it so important that people not starve?” he replied with biting irony.

His international stature is demonstrated by the fact that he served as the first chair of the academic committee of the Brussels-based House of European History, the flagship historical museum of the European Parliament. He was indeed a pro-European Polish patriot and a fierce opponent of nationalism, deeply fearful of the unleashing of violence and especially of Russia (and for that reason, in addition to Hungary’s ambivalent relationship to the memory of the Second World War, he held, I should add, contemporary Hungary in visible contempt). At the same time, in private conversations he would speak in a despondent tone about the labyrinths of Brussels bureaucracy, warning me not to engage with EU institutions if I was vested in “getting things done”—another perceptive advice of his that I subsequently failed to heed, I am afraid.

Borodziej also liked to quietly state that the House of European History would inevitably appear a failure, as it could never be more than a first attempt, one that would have to be followed by more convincing and more successful ones.

He left us way too early, in his mid-sixties—barely a few years after the opening of the House, which had taken so many years to prepare.

*

It is easier for me to write about Lutz Niethammer, because during the years we were in regular contact there was broad consensus about him: he was the grand old man of left-wing German historiography who possessed unmatched expertise—he was in fact considered something of a living encyclopedia of West German history. Indeed, nearly all historians in Jena regarded him as an exceptionally creative and truly brilliant historian even in old age.

He was almost the same age as my father; his own father had spent years in Soviet camps, just as my maternal grandfather had. The comparison may sound odd, but it is not insignificant: he was six when Nazi Germany surrendered unconditionally after an orgy of mass atrocities, while I was just one year older in 1989 when communist rule in Hungary ended with a whimper. Despite our significant difference in age, the turbulent history of the twentieth century thus ensured that we had obvious ways to connect.

Niethammer wrote numerous significant works and became famous, perhaps above all for his contributions to the then new field of oral history. His research in the GDR in the late 1980s acquired the status of a legend, and with full justification. He also used this expertise in his keen observations of colleagues: he had an unusually sharp eye for the distinctive traits of fellow historians and could compellingly analyze the connections between their interests, research agendas, arguments, gestures, tone of voice, and so on.

From a young age Niethammer was averse to the political Right, but he became a mature historian before the sharp anti-Nazi turn in West German culture. Without realizing it, he even studied under influential former Nazis—consistent, we may say, with the naïve postwar stereotype that educated and refined individuals could not have been Nazi perpetrators. In light of his early postwar experiences, he also regarded with skepticism the predominant contemporary German reverence for all things Jewish: he was ready to point out just how many of those eagerly atoning for the “sins of the fathers” still needed to learn to stop essentializing—to note openly, to paraphrase Hannah Arendt, that aus der Judenessentialisierung kommt man nicht so einfach heraus.

It soon dawned on me that Niethammer wanted to speak at length about every possible topic that mattered to him, but insisted firmly that most of my questions be readapted according to his preferences

One of the boldest decisions of my early career was to invite him, who was then my institute’s chief adviser, for a life story interview. Although I should have prepared more thoroughly, the occasion fortunately turned into one of the most fascinating and entertaining multi-hour conversations of my life. It became clear already in the opening minutes that I was sitting with one of the true masters of oral history and at the same time with a rather headstrong man. It soon dawned on me that Niethammer wanted to speak at length about every possible topic that mattered to him, but insisted firmly that most of my questions be readapted according to his preferences—on the noble principle that “I actually have much more to say on this.”

Niethammer produced much of lasting value throughout his distinguished career, though by his own, rather characteristic admission most of his intellectual experiments failed. He in fact appeared to believe that the escalation of conflicts could only be avoided by people learning to suggest guiding concepts they could also withdraw without losing face: as he half-jokingly put it to me, he was trying to spread the love of mistakes.

To my mind, what distinguished him the most from later generations of historians, who were arguably less original but more professional, was that Niethammer remained interested above all in people and in history as they experienced it, rather than in the current trends and debates of historical scholarship.

His imaginative, critical, often witty and always deeply historical mode of thinking, I believe, made a truly original contribution to the humanization of German culture in the postwar period.

He passed away last summer, just when I had begun to believe that he never would.

*

Mathieu Segers was born at a far luckier time and place: in 1976 in Maastricht, in the southern Netherlands, where some fifteen years later “world history,” or at least what was then believed to be of world historical significance—the signing of the Maastricht Treaty and the creation of the European Union—practically arrived on his doorstep. Yet the local boy could not physically approach the leading figures making epoch-shaping decisions for Europe, because the world, including the liberal democratic part of it, had evidently already entered an age of securitization.

It was a quarter of a century later that Mathieu Segers became my colleague at Maastricht University. Although he was a few years older than I, I—like many others, I presume—regarded him as something of a golden boy: he was evidently highly intelligent, tall, elegant, even charming, and altogether very worldly (he even had a reputation as an excellent footballer; he was—just like myself—a supporter of AS Roma).

His widely read commentaries and recommendations were known to be taken seriously by influential members of the state apparatus too.

Contrary to Dutch convention, Mathieu managed to achieve social scientific and public success, even gain some public influence, while regularly reading large and fabulous—including some rather little-known—novels and building his splendid essays around literary references. He struck me as someone who had a romantic streak tempered by a sharp analytical mind.

In a fundamentally technocratic country, in an age dominated by STEM, Mathieu Segers thus emerged as a distinguished spokesperson for history and literature. Through his fine depictions of broader cultural and political contexts that the Dutch public admittedly tends to be quite good at ignoring, he even came to be regarded in the Netherlands as “the voice of Europe.” His widely read commentaries and recommendations were known to be taken seriously by influential members of the state apparatus too. This was all very well deserved as he possessed nuanced insights into the history and theory of European integration both from a Dutch perspective and in a broader sense—in the four principal north-western European languages, one might say—and was able to communicate them in a most engaging manner.

Mathieu’s most essential virtue was perhaps his profound intellectual empathy: he could listen exceptionally well to what others were saying and build on their remarks with astonishing speed and depth without ever diminishing the original ideas.

His life was at once a romance and a tragedy: the golden boy suddenly fell gravely ill in his early forties.

He fought doggedly for years, but lived only to forty-seven.

*

As I indicated at the beginning, all three of these fascinating European historians had a profound impact on me. Borodziej perhaps most through his razor-sharp intelligence and humane realism. Niethammer through his deeply historicizing outlook, paired with an analytical admiration for the unique in humans. Segers through his empathetic attentiveness and worldly erudition.

It might be too facile to regard Borodziej’s acute intelligence and humane realism as an intellectual response to the existential threats Eastern European history has offered in such abundance; to see Niethammer’s historicizing vision and appreciation for individuality as products of the postwar intellectual opening and societal democratization of the Federal Republic; and to interpret Segers’s erudition and empathy as signs of a generation raised in the late-twentieth-century prosperity of Western Europe, at home in the world and most comfortable with being open to others. Yet it would be injudicious to deny the significance of such historical contexts and connections.

But our individual lives unfold as strange, startling, all too often tragic sequences of chance, we all know that—a fact illustrated by the irony that Lutz Niethammer, born in Nazi Germany in the very year the Second World War broke out, ultimately outlived both Włodzimierz Borodziej, a child of the ambiguous age of de-Stalinization, and Mathieu Segers, who was born into the peaceful affluence of the Netherlands in the 1970s.

The real question, however—just as Niethammer repeatedly emphasized—is how all the random encounters and unforeseen developments of our lives transform us, and what we make of them.

Ferenc Laczó is assistant professor with tenure (universitair docent 1) at Maastricht University and editor of the Review of Democracy (CEU Democracy Institute). He is the author or editor of twelve books on Hungarian, Jewish, German, European, and global themes.