A history of mass housing in Yugoslavia

Published by: Böhlau Verlag

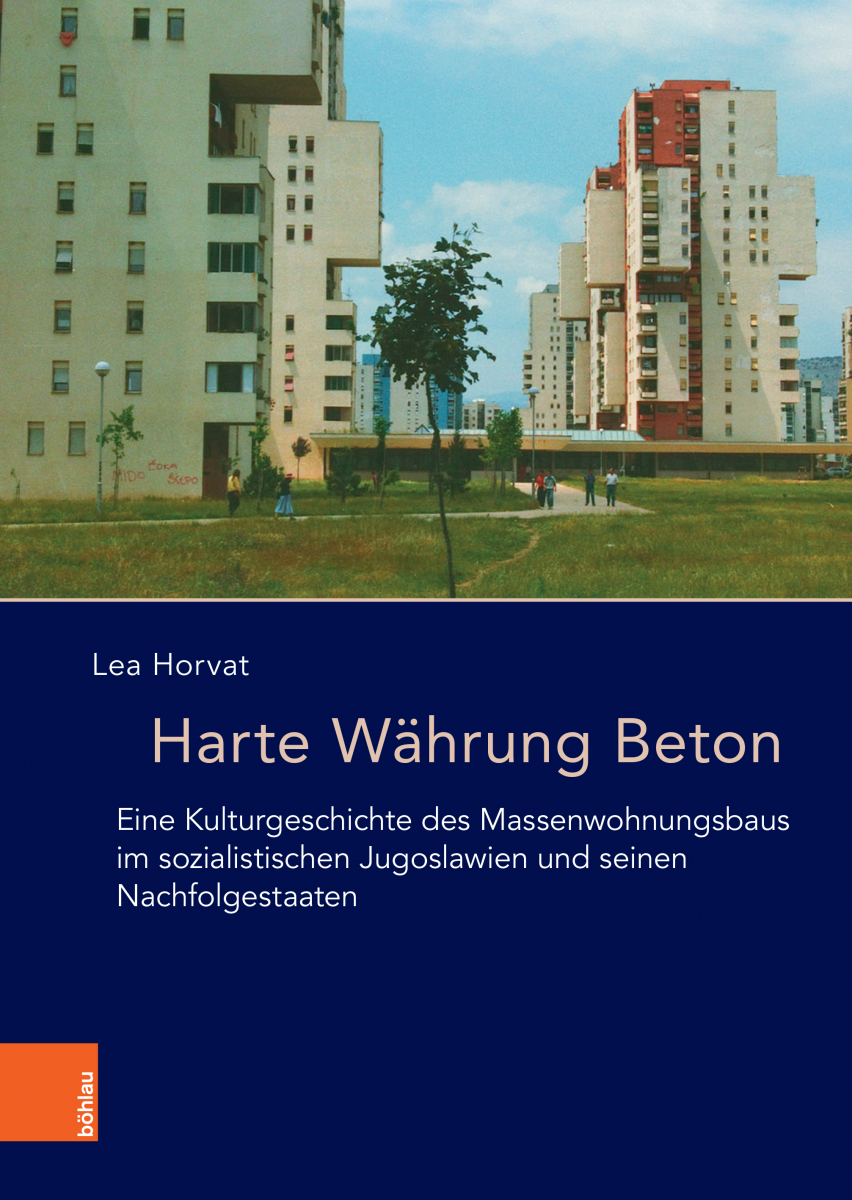

The German title of Lea Horvat’s book on mass housing in socialist Yugoslavia, Harte Währung Beton—which translates as Hard Currency: Concrete—comes from a letter published in Sarajevo’s daily newspaper in 1992. In the letter, the writer notes that, fortunately, the Housing Fund had not been destroyed, as it exists in the form of a hard currency—namely, concrete. This phrase immediately brings to mind another popular German term, Betongold, which is often used in the media to describe property investment as a low-risk, high-return strategy in times of monetary easing and low interest rates. The technical term for this phenomenon is financialization of the housing sector. In socialist Yugoslavia, however, hard currency had a different meaning. Coveted Western currencies such as the Deutsche Mark and the US Dollar—often kept in Yugoslav bank accounts—were used by savers as a hedge against the inflation of the Yugoslav Dinar. After 1992, as Yugoslavia dissolved amid both peaceful secessions and violent conflicts, the Housing Fund—which had helped build a large stock of mass housing since 1955—disappeared along with it, leaving tenants in apartment buildings and owners of single-family homes to rely on their properties as assets to navigate the hardships of war and the post-socialist transition.

Lea Horvat’s Harte Währung Beton starts with a short panoramic overview and an objective to provide a cultural history of Yugoslav mass housing from 1945 to the early 2000s. Following the tradition of cultural studies, the author draws not only from primary sources but also from a wide range of expert and popular media, including professional and lay magazines, films, domestic culture guidebooks, photographs, letters and so on. The chapters are organized chronologically and each chapter is assigned a specific set of sources.

The chapter Baustelle (building site) explores the heroic beginnings of Yugoslav mass housing in the late 1940s and 1950s. Using architects’ magazines of the era (such as Belgrade-published Architektura i urbanizam, Croatian Čovjek i prostor and Slovenian Arhitekt), the first chapter examines architects’ discourse on mass housing, revealing the familiar technocratic tropes typical of postwar Modernism. Like their counterparts in both the First and Second Worlds, Yugoslav architects saw prefabrication, along with typified and standardized design solutions at the scale of apartments, buildings, and housing estates, as the key strategy to solve the housing question. Horvat identifies a wide range of construction methods, styles, densities and typologies in the early years of Yugoslavia’s mass housing efforts. She attributes this diversity to economic inequalities, but also sees it as an opportunity to develop alternative solutions. The fact that large panel systems never became the dominant construction method in Yugoslavia—unlike in the Soviet Union, former Eastern Bloc countries, and even some Western nations—underscores the significant influence and relative autonomy of architects within the Yugoslav socialist system.

Horvat’s use of non-traditional sources such as how-to manuals and advertisements on modern domestic living contributes significantly to a better understanding of how users’ home cultures were shaped by the experts in these media.

The next chapter, Wohnung (Apartment) shifts the focus to the microscale of inhabitants and interiors. In this chapter, Horvat examines the rise of consumer culture during this era, which in the Yugoslav context of mass housing was shaped by spatial constraints and continued shortage, but mitigated by pragmatic, modern furniture and appliances and affordability. Using practical guides with advice on modern living and contemporary domestic interiors, as well as advertisements for home loans and furniture, the author highlights how shelter literature contributed to the reemergence of more traditional gender roles while endorsing hospitality for non-family members. Horvat shows that design guidelines recommended the allocation of a separate room for each child, thus reinforcing the central role of children within the socialist nuclear family – often at the expense of the couple, and even more so at the expense of women.

Wohnung is the most engaging part of the book: Horvat’s use of non-traditional sources such as how-to manuals and advertisements on modern domestic living contributes significantly to a better understanding of how users’ home cultures were shaped by the experts in these media. Home design guides and advertisements, but also floor plans with clear room designations, simultaneously empower users to consciously appropriate and design the space they inhabit, while administering normative restrictions on non-compliant practices and reinforcing the nuclear family and traditional roles within it.

The chapter Siedlung (best understood as a housing estate in the sense of a neighborhood) shifts the focus to the broader domain of large-scale residential developments. In this chapter, Horvat begins by recounting Yugoslavia’s increasingly troubled economic, political, and social landscape in the 1970s and 1980s. She then draws on two main sources for her analysis: first, the growing body of critical sociological studies on mass housing, and second, a detailed examination of two significant housing developments from that era—the seminal Split 3 housing estate and the lesser-known Blok 5 in Titograd (now Podgorica, Montenegro).

In Siedlung, the author demonstrates that, despite mounting opposition to the functionalist reduction, monotonous aesthetics, and lack of communal spirit in mass housing developments, the experts’ critique remained constructive. Through these two case studies, Horvat illustrates some of the novel architectural and urban planning approaches of the period. The seminal Split 3, a large-scale housing development, represents an effort to integrate varied densities within a walkable neighborhood, ensuring access to sufficient amenities and incorporating some non-residential uses. Blok 5 housing development on the outskirts of Podgorica is a rare case of introducing the concept of self-management into the spatial and material matrix of housing. The architect, Mileta Bojović, used novel modes of construction and implemented flexibility to enable user participation during the early design stages.

By focusing on the analysis of critical sociological studies and two model housing estates, Horvat’s exploration illustrates the continuing Western influence on Yugoslavia, complemented by the country’s strong tradition of regional modernism. Despite its strengths, the third chapter is also a missed opportunity, as it would have been an excellent moment to explore users’ perspective on the neighborhood in the context of self-management.

Under siege conditions, Horvat argues, urban living effectively became rural.

In the final chapter, titled Bild (Image), Horvat analyzes photographs and descriptions of Sarajevo by foreign correspondents to show how mass housing served as a backdrop during the city’s siege. She contrasts this external perspective with the experiences of residents who reappropriated their apartments as makeshift shelters and transformed the green spaces between housing blocks into allotment gardens for food. Under siege conditions, Horvat argues, urban living effectively became rural. The author concludes the cultural history of Yugoslav mass housing with a brief report on the right-to-buy schemes of successor states which transformed socially owned apartments into societies of owner-occupiers and profit-driven investors, with mass media reinterpreting mass housing estates as sites of social decline and crime. Although the chapter deals with some of the darkest episodes of the second Yugoslavia, Horvat manages to contrast the horrors of violence with the ingenuity of the inhabitants. Her vivid descriptions of some of the images in these chapters are not accompanied by the pictures described. This is probably due to the fact that the copyright for many of the images are increasingly difficult to obtain.

The book concludes with a Fazit und Ausblick (Summary and Outlook) in which the author eloquently and concisely reviews the book’s main take-aways.

In the absence of a comprehensive architectural history of socialist Yugoslavia, Harte Währung Beton serves as a valuable resource for historians across disciplines who seek to explore and reinterpret second Yugoslavia’s unique and complex past. For architectural historians, the book provides a compelling approach to understanding how residential architecture, domestic interiors, and postwar modernist neighborhoods were historically perceived through popular and mass media, revealing previously overlooked dimensions of the built environment.

Maja Lorbek is an architect and architectural historian. She completed her doctoral studies at TU Wien, where she also worked as a lecturer. She later served as project coordinator/researcher at the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Research (IOER) in Dresden.She is currently leading the research project “Transnational School Construction” funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). Her research focuses on the history of ideas in architecture and education.