An intimate history of Eastern Europe

Published by: Oneworld Publications

Mikanowski’s Goodbye Eastern Europe is hard to define – at times memoir, at times a work of history, at times a dive into myth and legend. It is a diverse work in this respect, a perfect fit for the region it describes. From the Russian invasion of Ukraine to concerns about democracy in Poland and Hungary, Eastern Europe has been a constant presence in newspapers and television channels. But like Mikanowski’s work, the same challenge arises – what is it, and how do we define and understand it? In this, the work finds its strength. Mikanowski aims not to create a singular unifying narrative, but instead to embrace the contradictions of the region, drawing attention both to the mighty imperial capitals of Vienna, Budapest, Moscow and the towns and people that inhabit the peripheries.

The book is divided into three sections, following a chronological approach – from early faiths, to empire, before finally reaching the twentieth century. Each section takes a thematic approach in its chapters, drawing upon examples and anecdotes from across both the life of the author and the region at large.

Mikanowski writes how the varying faiths of the region experienced diversity – from Islam’s central role in the establishment and growth of Istanbul and Sarajevo, to the supernatural elements that were ubiquitous throughout both Jewish and Christian areas. It is here where Goodbye Eastern Europe captivates.

In Part One, Faiths, Mikanowski delves into the varying religions of Eastern Europe – their origins, their development and their unique features. For Christianity and Paganism, he suggests a political aspect to faith; be it opposition to the Holy Roman Empire or outside invaders, while later becoming a local identifier. For the Jews, Mikanowski elaborates on how Eastern Europe represented tolerance in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire, but later oppression and massacres during the Khmelnytsky Uprising. For Islam, the divide in how Eastern Europe can both be presented as the periphery of the Islamic world whilst simultaneously representing the edge of Europe. Throughout these three chapters, and the final on Heretics, Mikanowski writes how the varying faiths of the region experienced diversity – from Islam’s central role in the establishment and growth of Istanbul and Sarajevo, to the supernatural elements that were ubiquitous throughout both Jewish and Christian areas. It is here where Goodbye Eastern Europe captivates. From the Golem of Prague to stories of vampires, Mikanowski avoids the ‘othering’ that so commonly accompanies these myths, instead placing them firmly in the lives and environments he describes, seamlessly integrating them in a manner that feels natural yet entertaining.

Part Two, Empires and People, begins with the vital point that being Eastern European is often not a story of self-rule, but one of governance from an imperial capital. It is here where Mikanowski returns to discuss the idea of Vienna, Moscow, Istanbul and Budapest as central to history. These are each accompanied by caveats – from the role of luck in the rise of the Habsburgs, to the corruption in everyday life in Istanbul, these imperial capitals are not presented as glittering metropoles. In many respects, they are presented as witnesses to the history and culture that was being developed elsewhere under their reign. From the diversity of Timișoara to the segmented nature of Chernivtsi, it is the cities and people far from the center that are explored at length. In this, the stories of nations and individuals are built; the oral histories of the Roma, the wealth of linguistic diversity, and the role of poets like Mickiewicz and Eminescu. Mikanowski is cautious to caveat this, however, with these peripheral cities also demonstrating the horrors of the enslavement of the Roma and the birth of nationalism. It is also in one of these cities that the chapter finds its culmination, with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, far from the home of the empire in Vienna and Budapest.

Nowhere is this theme of contradiction and diversity shown as eloquently as in Part Three, the Twentieth Century. Modernity is presented as an aid through Budapest’s metro to the lights of Lviv and Timișoara. Yet it is also shown to bring darkness through military technology and the growing presence of fighter planes. With this, new ideas are developed – Fascism and Communism. It is nowhere more than here that the theme is most evident. From the very nature of these starkly differing ideologies to the role of the ideologues that embraced and espoused them, Mikanowski notes diversity. Lenin and Horthy, to Stalin and Tito, Ceaușescu and Codreanu, these individuals presided over atrocities and horrors throughout the period. This is another area in which Goodbye Eastern Europe has strength – it does not relativise these individuals but instead places them firmly within their specific contexts.

It is clear that this work does not aim to re-invent the study of Eastern Europe. It is not an academic tome, but it is meticulous in its depth and research.

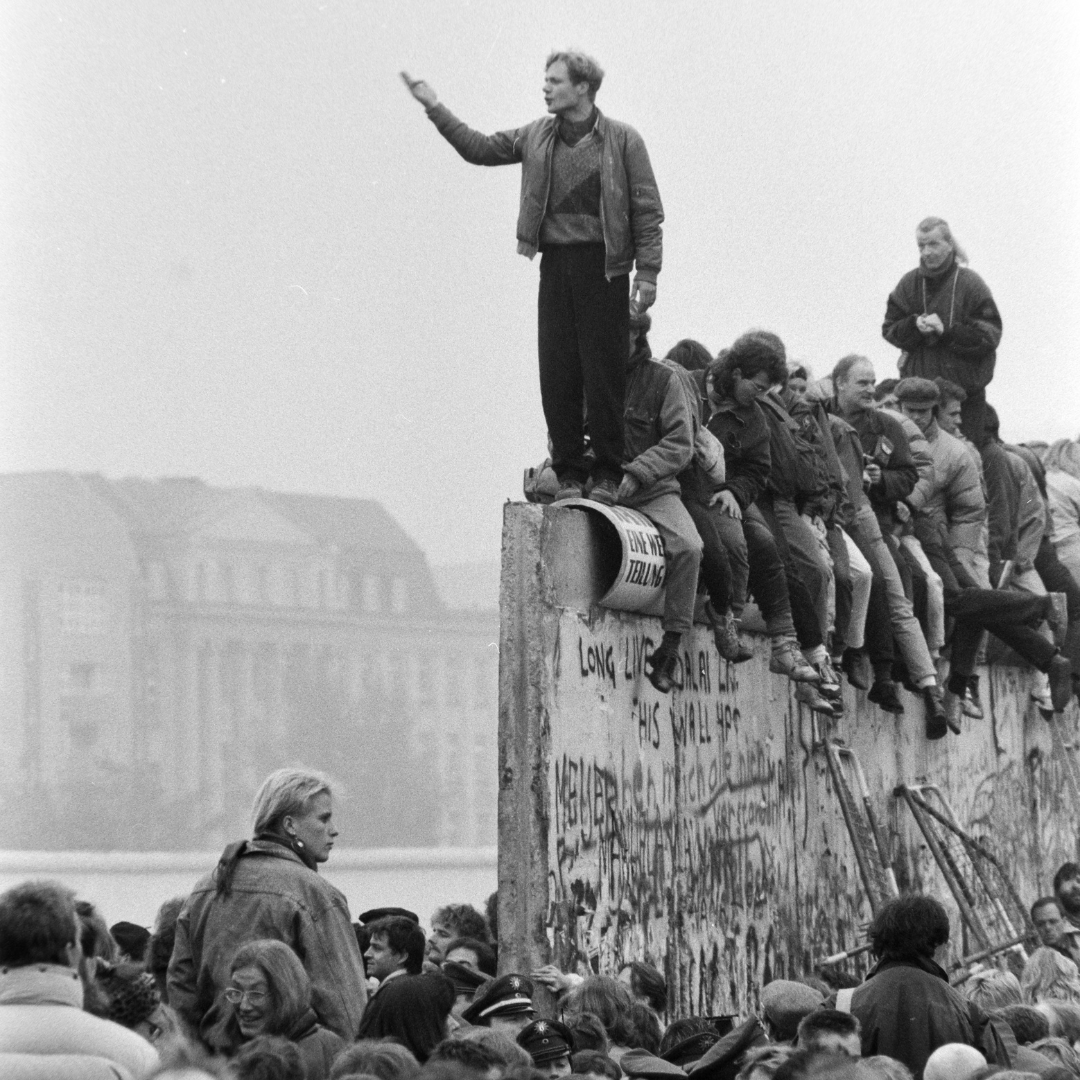

The ears and eyes of these totalitarian regimes are described at length, but without the usual focus on Hitler’s Schutzstaffel (SS), the East German Stasi or the Russian KGB. Instead, Mikanowski delves into the Czechoslovakian StB, the Hoxha regime’s Sigurimi, and the Romanian Securitate. Whilst comparisons to these more familiar secret police organizations may be useful for the lay reader, they are a standout feature, providing a clear distinction between Goodbye Eastern Europe and many other works on the market. This is furthered by the description of the revolutions and machinations that brought the Warsaw Pact and the Communist parties of Eastern Europe to an end. With reference to Glasnost and Perestroika, but a focus firmly on the downfall of individual regimes, Mikanowski delicately addresses the similarities and differences in what otherwise may appear uniform.

It is clear that this work does not aim to re-invent the study of Eastern Europe. It is not an academic tome, but it is meticulous in its depth and research. Goodbye Eastern Europe does, however, fill a vital role – providing a history of a commonly misunderstood and maligned region. Mikanowski’s work is a contradiction that describes contradictions, and it is masterful in achieving this. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, one cannot help but reflect on Mikanowski’s remark that the lives of everyday east Europeans are shaped by powerful figures from imperial capitals. Whilst this thought is likely to linger in the reader’s mind, so should the stories of hope and progress that are presented throughout. Goodbye Eastern Europe is a perfect introduction to Eastern Europe to anyone unfamiliar to the region, whilst the familial history that is interspersed throughout creates interest even for those who are scholars of any of the states involved.

Jack Dean is a Ph.D. candidate at University College London’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies, where he works on the sociology and politics of Central Europe. His dissertation Medical Populism in Romania, but his research interests address the region more broadly, with particular focus on 1945 onwards.