Austrian migration and asylum policies during the Cold War

Published by: Transcript

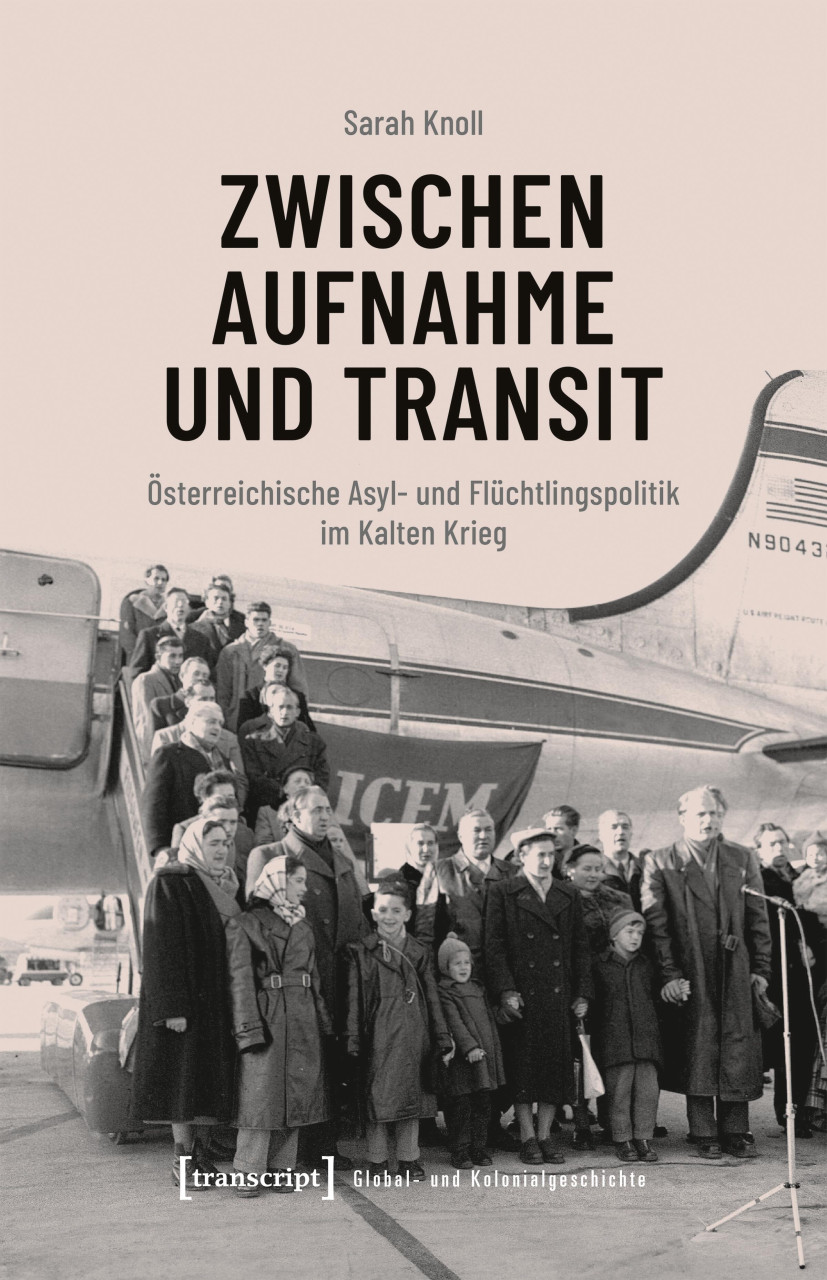

Despite the East-West divide and the crystallization of Europe into two blocs, during the Cold War people were moving across borders, challenging the idea of an impenetrable “Iron Curtain”. From 1956 Austria was at the crossroads of different trajectories that led people from the Eastern Bloc into the “West”. Zwischen Aufnahme und Transit. Österreich Asyl-und Flüchtlingspolitik im Kalten Krieg by Sarah Knoll discusses how Austria reacted and managed the population movements resulting from major Cold War tensions and changes. During 1956 and 1968 Hungarian and Czechoslovakian citizens left their countries because of the upheavals of the Hungarian Revolution and Prague Spring and the consequent repression of protests. Between 1981 and 1982, the rise of Solidarnoćś, the demonstrations against the regime, and the establishment of military law led Polish citizens to leave the country, and in 1989 the easing of travel from East Germany to Hungary and the progressive opening of the Hungarian-Austrian border facilitated population movements from the German Democratic Republic (1989). Finally, the persecutory policies of the Nicolau Ceausescu regime in Romania toward minorities and the difficult economic situation motivated Romanian citizens to leave the country (1989-1990).

The book provides a detailed narrative of Austrian migration policies in the Cold War context. Sarah Knoll tells the story of refugees’ reception in and transit and through Austria through the innovative lens of the actions of humanitarian agencies. From the perspective of international history, Knoll discusses humanitarianism in a wider geopolitical picture, but she still anchors the topic within Austrian history. The author demonstrates how national, international, state and non-state agencies played specific and equally important roles in the making and implementation of refugee policies in Austria. The refugee support actions of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Red Cross are discussed in depth. In this way, the idea of the nation-state as the sole actor in migration policies is challenged: Austrian history is marked by a very intense collaboration between the state and the non-state agencies.

Non-state actors played a major role in Austrian migration policies, to the point that non-state agencies managed areas that usually come under state control, such as the issuing of immigration documents. This emerges clearly in 1956 and 1989. Non-state private organizations such as Caritas and Volkshilfe were quickly ready in 1956 to put in place support actions for the Hungarian refugees (p. 52), thus showing how impactful the presence and rootedness of such agencies was on Austrian territory. In 1989, the Red Cross directly managed not only the provision of first aid and support to the refugees, but also the immigration bureaucracy. While the Red Cross’s actions and relationship with the Austrian state are discussed in depth, other non-state agencies remain in the background of Knoll’s narrative. Further research in this field can explain the motivation and methods of civic and religious forms of humanitarianism in Austria. Moreover, an understanding of the pre-1956 role and position of non-state agencies during the occupation period would give interesting insights on the role of the Austrian state and its devolution of responsibility to humanitarian agencies from 1945 to 1955. New research in this field would also add more layers to Knoll’s explanation of the rapid response of non-state organizations to the need to support refugees. While she argues that more time was needed for the UNCHR agencies to prepare, it may have been the case that local Austrian associations like Caritas had a longer and better-established network in the country. This remains an untold story.

the East-West confrontation started to lose its poignancy. The citizens of Poland and Romania crossing borders to the “West” were perceived as economic migrants and therefore as a potential threat for the internal Austrian job market, rather than as escapees from Communist dictatorship.

In 1956, the Christian Science Monitor newspaper pointed out how Austrian migration policies placed “the heart of neutral Austria in the West” (AdR, BMfI,12U/12A/34 SG I-5.1 Kt. 9). In fact, despite Austria’s just gained neutrality, Austrian policy makers used the Western concept of “political” refugees (according to the Geneva Convention of 1951), implying an anti-Communist stance, as it marked the refugees as “freedom fighters” opposing the Eastern Bloc regimes (p. 48). To avoid any challenge to the Austrian-Soviet relationship, the humanitarian agencies played a key role in repeatedly underlining the “humanitarian value” of their support actions and the absence of any political meaning. The East-West divide, humanitarianism, and politics went hand in hand in the making of refugee policies.

Political and economic changes had an impact on refugee policies during the Cold War. Knoll points this out especially in relation to the late 1960s the UNHCR was less keen to use the label in order not to jeopardize the Deténte (p. 134). The economic boom in Europe came to an end and the role of the refugees “from the East” in the job market became less evident. At the same time, the East-West confrontation started to lose its poignancy. The citizens of Poland and Romania crossing borders to the “West” were perceived as economic migrants and therefore as a potential threat for the internal Austrian job market, rather than as escapees from Communist dictatorship. Knoll shows how population movements are not to be understood separately from political and economic changes. Rather, they are deeply intertwined and they all impacted the Austrian reception of refugees, either boosting anti-Communist solidarity, or sparking protests against the presence of refugees in Austria.

Knoll underlines a common factor that connects 1956 to 1989: the political will of Austria to act as a transit country. Hence, the Austrian government aimed to at the same time offer first aid to the refugees in Austria while pursing active international campaigns to secure their resettlement in other countries. While for Hungarian, Czechoslovakian, and Polish citizens the Austrian government actively reached out to the international organizations to request support in the management of the further migration of the refugees, in the cases of the GDR and Romania Knoll shows how the Austrian authorities initially pursued a different strategy. Through the help of humanitarian organizations, they supported relief actions abroad, in the hope that a better situation at home would lead to less border trespassing. Knoll points out how this attitude in the 1980s intersected with Hungarian political and economic interests for progressive integration with the “West” (p. 240). Furthermore, Knoll’s findings on the role of the Hungarian Red Cross could offer an interesting contribution to the discussion on the role of civil society in the last decades of Communist rule in the Eastern Bloc.1

Sarah Knoll manages to pull together the threads of the Austrian migration policies after 1955 and to successfully connect them to the Cold War and the international and socio-economic context. The book develops a story that has often been overlooked, namely not only how migration policies are influenced by the political context, but also how they can strongly influence inter-state relations. Sarah Knoll’s book offers the chance to reflect on the identification of trends or breaks with Austrian post-1945 migration and integration policies. In conclusion, Zwischen Aufnahme und Transit. Österreich Asyl-und Flüchtlingspolitik im Kalten Krieg contributes to the discussion of migration policies in Austria by providing for the first time an inter-connected story of international, national, and non-state actors.

Emma Dal Mas is a Doctoral Student at the European University Institute. She holds a master’s degree in history from the University of Trieste, and a bachelor’s degree in literature from the University of Udine. Her research deals with the public-private management of the German refugees in Austria after 1945. Before joining the EUI, Dal Mas held the position of research assistant in the project “Cultural heritage of war on the borderland. History and memory” at the University of Udine, where she investigated memory and commemoration practices of the First World War in Northern Italy. At the University of Udine Dal Mas was also responsible for the project Time Travelers. Friuli Venezia Giulia as a handbook of the XX century.

1 Béla Greskovits, “Rebuilding the Hungarian right through conquering civil society: the Civic Circles Movement” in East European Politics No. 36 Vol. 2 (2020), 247-266, DOI: 10.1080/21599165.2020.1718657.