Beauty contests and women’s agency in early-20th-century Germany

Published by: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

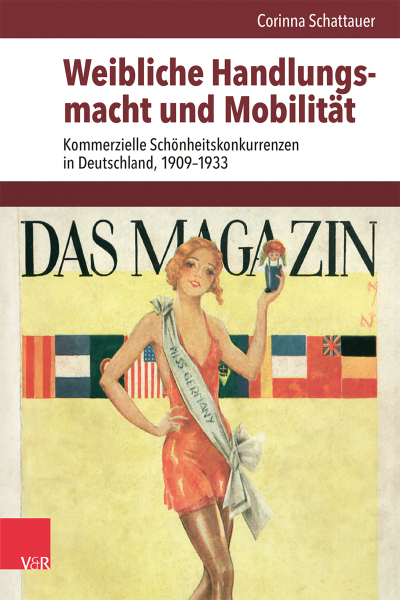

For the past two decades, countries around the world have been searching for their own “Next Top Model” on widely popular TV shows. These shows follow the principles of beauty contests, which, since the late 19th century, have publicly placed women and their bodies in competition with one another. While the TV show format is highly popular in Germany, scholarly research has so far paid little attention to its historical predecessors. Investigating commercial beauty contests in Germany between 1909 and 1933, Corinna Schattauer’s study Weibliche Handlungsmacht und Mobilität makes an important contribution to filling this gap.

While using these contests to address nationalization and transnationalization processes during the interwar period, Schattauer’s study is situated more within research on practices of competition and comparison, as well as historical mobility studies. The book argues that between 1909 and 1933, women were able to utilize beauty contests “for themselves and their (transnationally oriented) careers” (p. 18).

The book argues that such instances illustrate how the commercialization of their bodies enabled women to use competitions to gain a certain level of economic independence

Drawing on Bourdieu’s types of capital and placing great emphasis on women’s agency, Schattauer contends that contestants “purposefully used their bodies to […] increase their economic, social, and symbolic capital” (p. 14). A strong position in a competition could ideally lead to an “upward spiral,” (p. 285) in which social and spatial mobility reinforced one another. For instance, following her participation in several beauty contests, the model Maud Feller (born Elke Zarske) was able to move within Berlin’s high society. In this context, she met Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, an heir to the Thyssen fortune, and later married him. After being crowned “German Fashion Queen” in 1926, Sonja Jovanowitsch signed several advertising contracts, including for hair removal cream, and was also hired for fashion shows and acting roles. Similarly, Jaggi Grasmann, the 16-year-old winner of a lavish beauty contest organized by a cosmetics company in 1928, secured a role at the Dresden Theater, as well as advertising contracts for cigarettes and cosmetics, including for the company’s own shampoo brand, Pixavon.

Schattauer sees in these women “much more than just passive projection surfaces” or “playthings of the companies that had elevated them” (pp. 199-201). The book argues that such instances illustrate how the commercialization of their bodies enabled women to use competitions to gain a certain level of economic independence while also increasing their visibility and recognition within society. This interpretation reflects the stated aim of the study: to trace women’s agency within commercial competitive contexts. At the same time, it leaves the reader with critical questions about the scope of female agency in a consumer society. How far does agency really extend when a career becomes possible primarily through self-objectification and commercialization within a capitalist market logic dominated by men?

Given these reflections, it becomes all the more important to give voice to the participating women themselves. How did they understand and interpret their own actions? In this respect, the study falls short of the expectations it raises at the outset. It reconstructs women’s subjective experiences primarily from representational sources, including official and corporate archival materials, newsreel footage, newspaper and magazine articles, as well as fictional works such as novels, plays, and even paintings, most of which were produced by men.

Citing sociologist Andreas Reckwitz’s concept of the hybrid subject, Schattauer argues, for example, that women participants actively embraced their visibility, thereby reversing traditional roles and turning male spectators into the observed. To support this claim, she refers to an advertisement by the cosmetics company Elida, which promoted the idea that women who used its products would not only appear more attractive to men but would also be better equipped to withstand critical glances. The study interprets this claim as an attribution of agency to women, suggesting they could determine “how they were perceived from the outside and, more importantly, how they dealt with that perception” (p. 166).

Elsewhere, the author examines the portrayal of a naked woman being judged by a male jury in Anton Räderscheidt’s painting Die Schönheitskönigin. While the woman is undoubtedly “presented as an object of display, exposed to the gaze of an anonymous group, she also appears to present and offer herself to that gaze willingly, without any visible signs of embarrassment or shame.” This expression, the study argues, “could be interpreted as passivity or indifference, but also as a form of composure, one that stems from the beauty queen’s awareness of her own bodily appeal and her confident presentation of it” (p. 169).

Where the study does incorporate ego-documents, a more nuanced narrative surfaces. Leni Riefenstahl, for instance, recounts in her memoirs the discomfort she felt when, following her participation in a beauty contest, the editor-in-chief of Das Magazin invited her into a separate room to discuss potential career opportunities, only to demand that she lift her skirt above the knee so he could inspect her legs. Christian women’s organizations, in turn, rejected the competitions altogether, arguing that they turned women into objects on display.

Schattauer also demonstrates compellingly how standards and norms for female bodies were both practically and discursively produced and reproduced in the context of these contests.

While the study reconstructs some women’s career paths and supports the notion that some of them achieved upward mobility, it would have benefitted from a more sustained engagement with ego-documents and the self-interpretations of the women involved. This engagement would offer rich ground precisely regarding the question of women’s agency in the context of beauty competitions.

The study is strong, however, where it examines the restrictions and demands placed on women participating in these contests. In a particularly illuminating section of the study, Schattauer shows, for instance, that “women who were not ‘white’ enough were excluded from accumulating capital through beauty competitions” (p. 139). Unsurprisingly, a strong erotic component ran through the evaluative practices of beauty competitions. The constant eroticization of the female body was especially evident in the role played by juries, who were predominantly male. Jurors – including film director Fritz Lang as a regular judge – acted as “experts” who claimed to possess a professional gaze toward the contestants, one that was allegedly detached from erotic perception. All the more revealing, then, was the evaluation scale of the Reichsverband für Schönheitskonkurrenzen, which claimed to ensure objective comparability in its contests by judging women according to whether they were “beautiful enough to attract (male) attention in everyday life” (p. 122).

Through meticulous examples, Schattauer also demonstrates compellingly how standards and norms for female bodies were both practically and discursively produced and reproduced in the context of these contests. Das Magazin, for example, calculated the measurements of the statue of the Venus de Milo and invited its female readers to submit their own measurements for comparison with those of other women. Other newspapers published contest winners’ weight and body measurements, enabling and encouraging their female readers to compare themselves with these women. As a result, women learned to “aspire to socially accepted beauty ideals through the competitions” (p. 124).

The study develops one of its most compelling arguments in relation to these beauty ideals. At the Miss Germany contests of the Weimar Republic, the dominant ideal of beauty was characterized by curves and long hair, features that stood in clear contrast to the more “angular” male body. Schattauer convincingly argues that the “female bodies put on display” in these competitions contributed to reasserting “the separation of the sexes, a distinction that had been unsettled in the years following the First World War” (p. 132).

Thanks to its vivid writing style and close engagement with sources, Corinna Schattauer’s study will appeal not only to historians across various subfields but also to non-specialist readers. By tracing the historical development of beauty contests and the commercialization of appearance, she provides valuable context for understanding why women – and increasingly also men – find themselves in constant competition over “attractiveness”. Moreover, it explores the role of so-called experts, mass media, and what we would now call influencers as key mediators in the circulation and normalization of beauty ideals so relevant to society. At the same time, the question of how much these women succeeded in asserting a kind of agency to build freer lives and careers remains open for future scholarship.

Louisa Niesen is a PhD researcher in history at the European University Institute in Florence. Her dissertation examines the relationship between the changing leisure travel practices of German-speaking Central European women and the development of related infrastructures between 1880 and 1914. She holds an MA in Cultural History from Utrecht University, where she graduated with a thesis on female employees in the Weimar Republic. Louisa has taught courses at Utrecht University and the University of Padova. With experience in museum work and exhibition curation, she co-convenes the Public History working group at the EUI. Recently, she co-organized a museum curation workshop in collaboration with curators from leading European institutions.