Bessarabia and the collapse of empires

Published by: De Gruyter

The geopolitical transformations following the First World War and the collapse of empires have become a well-established area of historical research. After 1989, certain historiographies in East-Central Europe were dominated by nationalist perspectives that portrayed nation-states as emerging solely from secular aspirations of self-determination and unification. However, scholarly works of the past decade have deconstructed this narrative, revealing the complex and challenging political processes involving continuities and changes that affected institutions, policies, elites, masses, ethnic and religious groups, and even individual identities in the face of the new world order. Some interpretations suggest that the war did not truly end after 1918.1 The post-war years were marked by tensions in many of the states created by territorial annexations, tensions that escalated during the interwar decades. Stability often required adherence to tradition and continuity rather than abrupt changes.

Suveica meticulously reconstructs a dynamic and tension-filled transnational history of Bessarabia’s political transition from empire to nation-state.

The post-war histories of provinces formerly integrated into Austria-Hungary (such as Transylvania and Bukovina) and the Russian Empire, such as Bessarabia, which joined Romania after the First World War, are marked by similar developments and are characterized by conflict, struggle, and resilience. In the case of Bessarabia, these dynamics are vividly explored in Svetlana Suveica’s recent work, Post-Imperial Encounters: Transnational Designs of Bessarabia in Paris and Elsewhere, 1917–1922. Suveica, a historian well-versed in Bessarabian history, provides a comprehensive analysis that not only examines the region’s perspective but also considers the defunct empire and Western states, including the nationalizing Romanian state. By adopting these multiple perspectives, the author focuses on the local agency of the former regional elite of landowners with diverse political views, who engaged in informal negotiations in Paris and Bessarabia to counter the political control exerted by the Romanian nation-state over the Bessarabian province. Suveica meticulously reconstructs a dynamic and tension-filled transnational history of Bessarabia’s political transition from empire to nation-state. In tracing movements and actions across national boundaries founded on Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the author illustrates the spatial transformations of this borderland and amplifies the voices of individuals interconnected within a social network dominated by the figure of Alexander Krupenskii, former Marshal of the Bessarabian nobility and leader of the “Bessarabian delegation” to the Peace Conference.

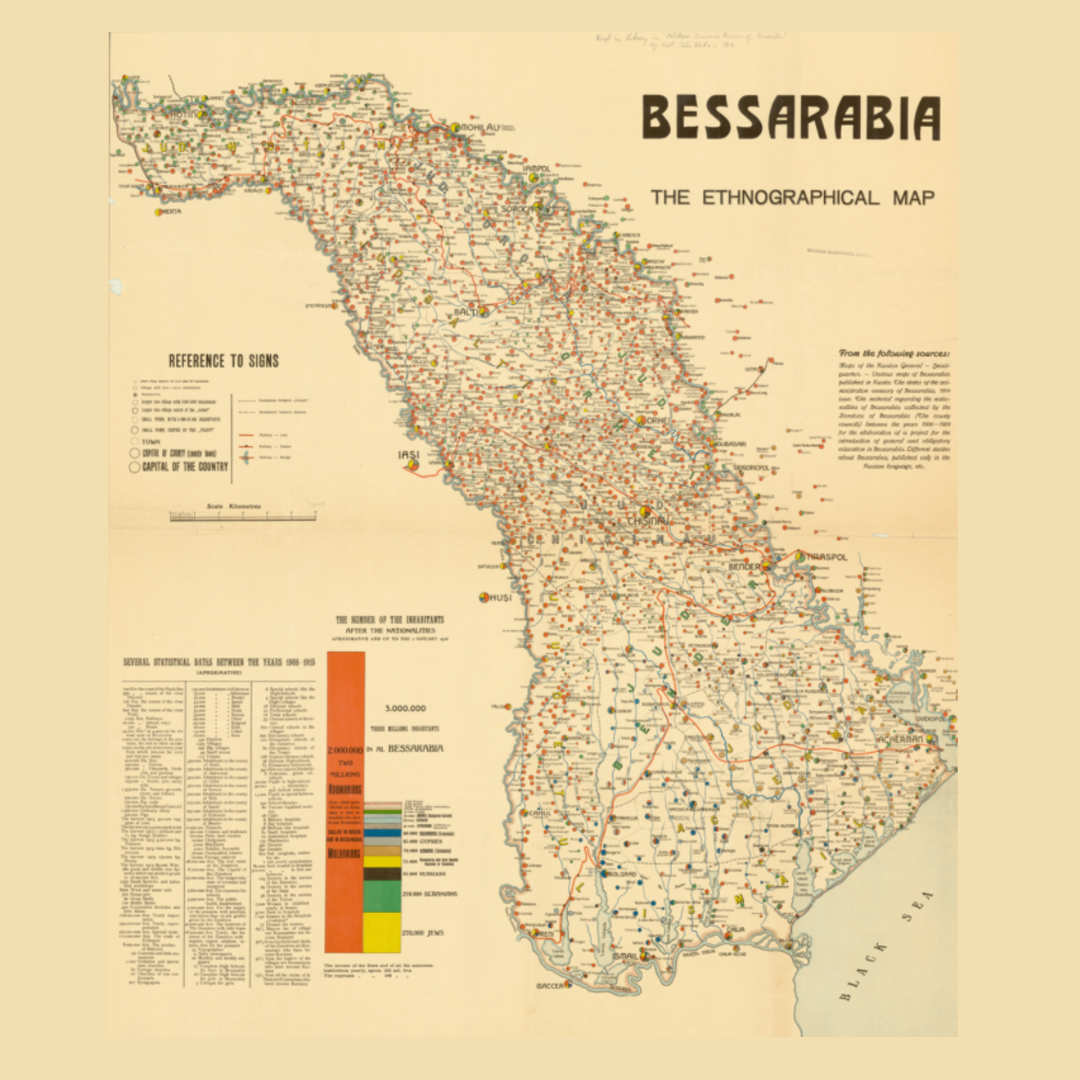

The evolution of this network in search of alternative projects to nation-states is presented in eight chapters, each progressively depicting the conditions experienced by the Bessarabian elite, from initial drama to eventual resignation. The first chapter, titled “The Drama,” sets the scene surrounding the “Bessarabian question,” focusing on the discussions at the Quai D’Orsay on 2 July 1919. During these talks, Romanian and White Russian representatives presented contradictory claims based on historical arguments regarding Bessarabia’s affiliation with Romania and the Bolshevik threat, while the Russian side contested the legitimacy of the national assembly (Sfatul Țării). The second chapter (“Liminality”) highlights the transitional state of the Bessarabian elite, positioned in a state of anticipation amidst the backdrop of the Bolshevik Revolution and the uncertain future ahead. This chapter traces the post-war phases of the borderland, beginning with the establishment of the Sfatul Țării (November 1917), followed by temporary forms of regional autonomy, such as the proclamation of the autonomous Moldavian Democratic Republic within the Russian Democratic Republic (December 1917), and subsequently the independent Moldavian Democratic Republic (February 1918), culminating in the Union with Romania (March 1918).

the history of East-Central Europe encompasses not only successful developments but also failed projects, vanished worlds, and lost struggles.

The subsequent three chapters (“Illusion,” “Hope,” and “Struggle”) illuminate the adaptation strategies and endeavors of the Bessarabian elite during the period when the region had temporary autonomy under Romanian rule (April-December 1918). As negotiations for positions within the regional administration proved unsuccessful, the “Bessarabian delegation,” formed of radical and moderate factions of the elite, fruitlessly hoped for alternative solutions at the Peace Conference in Paris. Excluded from the Conference discussions, they propagated extensive anti-Romanian sentiments through the press. In the sixth chapter entitled “The Network,” the author details interconnected actors by visually mapping connections among 49 individuals divided into two groups: Bessarabian and Russian emigres in Switzerland, along with their supporters. Finally, in the last two chapters (“Ambivalence” and “The Loss”) Suveica traces the resignation of these actors from their failed political endeavors amidst an atmosphere of doubt and anxiety. Furthermore, the author shows that while regional identity was contested within Greater Romania, the self-identification of the Bessarabian elite, at least in private spheres, persisted as “Russian by name and in the soul.”

This volume compellingly demonstrates that the history of East-Central Europe encompasses not only successful developments but also failed projects, vanished worlds, and lost struggles. Post-Imperial Encounters brilliantly illustrates the complexity of post-war transformations by giving voice to local actors who are often overlooked in triumphalist national narratives. Suveica extensively explores archival material, notably focusing on the extensive correspondence of Krupenskii in the Hoover Institution Archives in Stanford, California. Framed by a solid theoretical and methodological foundation, the volume makes a significant contribution to the history of Bessarabia through the lens of post-imperial continuities. This work will appeal equally to historians of interwar Romania, offering new insights for a deeper understanding of regionalism within a national state and highlighting the decisive influence of the international context on national evolutions. Like any scholarship addressing complex historical processes, the book also paves the way for further research, such as exploring survival and adaptation strategies among the broader Bessarabian population or examining the positions of ethnic minorities confronting new nationalizing majorities.

Anca Filipovici is a researcher at the Romanian Institute for Research on National Minorities in Cluj and a historian of ethnicity and antisemitism in interwar Romania, with a focus on the history of Jews and the history of youth and political activism. She is the recipient of several fellowships from Romania, Austria, and Germany, and was recently awarded the C. and N. Weickart Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Fritz Bauer Institute in Frankfurt am Main, for the period 2023-2024.

1 See for instance Tomasz Pudłocki and Kamil Ruszała (eds.), Postwar Continuity and New Challenges in Central Europe, 1918–1923. The War That Never Ended. New York, London, Routledge, 2022.