Debunking miracles in Polish history

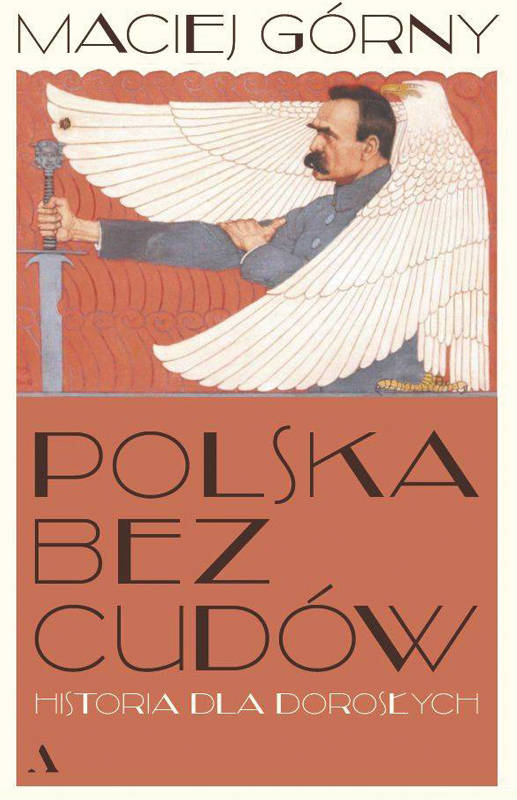

Published by: Wydawnictwo Agora

The field of Polish history is something of an ideological and political battleground, so the title of Maciej Górny’s book must be understood as a salvo of artillery, announcing that a combatant of formidable strength has launched an assault. Polska bez cudów: Historia dla Dorosłych [Poland without Miracles: History for Grown-Ups] is a highly polemical work by one of Poland’s foremost historians. Against much of the effusively patriotic and highly romanticized narratives of Poland’s past that remain popular in that country, Górny’s book seeks to de-mythologize the Polish past and reveal the messy, and sometimes unsavory, reality behind the grand stories and glorious myths.

History for Grown-Ups is not a narrative. Instead, it consists of 14 chapters, most of them focused on the period of the First World War and the establishment of the Polish state in its immediate aftermath. (An editorial postscript, which should have been put at the beginning of the book, helpfully explains that History for Grown-Ups is a collection of the author’s articles and essays, some of which appeared in edited volumes, and others of which appeared in publications such as the newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza). The chapters each deal with a different key event or experience from the era, with Górny first setting up, and then knocking down, the popular-romantic view of them. For example, Chapter One, “The Fratricidal Battle” (Walka bratobójcza), is devoted to the Polish experience of the First World War. It begins with Górny invoking the patriotic poem of a Polish Legionary who, in 1914, lamented the fact that Poles in the war would be forced to fight against one another. This view, Górny notes, has become the generally accepted view of the fate of the Poles during the war: that they were uniquely cursed to battle one another in an unwanted fratricidal struggle forced upon them by outsiders.

He goes on to illustrate, however, that there are several problems with this view. One is that many nationalities in central Europe (including, for example, the Ukrainians) fought against one another in the war; such was the nature of the multi-national militaries of the empires who ruled there. Another is that most Polish soldiers seem to have loyally served their respective kings and emperors, and not been overly troubled by the supposedly “fratricidal” nature of the war they were engaged in. The deceptive claim to Polish exceptionalism is one that Górny attacks repeatedly throughout the essays in the book. His view of the period is perhaps best summed up in a quote that concludes his chapter on the tension between multinational ambitions and nationalist realities in the postwar period, when idealistic views of federations and alliances, both domestic and foreign, competed with nationalist state-building projects that emphasized a given nation’s language and culture. “At . . . [the] very same time” that the Poles were working to create a new state, he writes, “Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Belorussians pursued their own state-building enterprises, neither better nor worse than those of the Poles.” (p. 107)

Górny insists that and honest reckoning with the region’s past is needed “because there are no miracles”.

Another chapter, “Without Miracles,” [Bez cudów] vividly illustrates Górny’s other major theme: the chaotic nature of historical reality before it becomes turned into a myth or fable. As its title suggests, the chapter deals with the Polish-Soviet war and its culmination in the so-called “Miracle on the Vistula,” when Józef Piłsudski, Commander-in-Chief of the Polish army, and the soldiers of the newly restored Polish state stopped the Bolsheviks’ drive on Warsaw. The importance of the entire affair, still a source of pride to Polish patriots, has been much overblown, Górny argues. He suggests, for example, that the title of Edgar Vincent, Viscount D’Abernon’s 1931 book, The Eighteenth Decisive Battle of the World: Warsaw 1920 should never have been taken so seriously. Górny makes this point by providing an overview of the viscount’s unsavory and unsuccessful banking career, along with a few critical sentences about what he sees as the viscount’s overly benevolent attitude toward Germany when he served as ambassador in the 1920s, before jeering that “such an authority as this has, for many years now, assured us that the battle of Warsaw was one of the most important in the history of the world.” (210-211) A fair claim, perhaps, but somewhat unfairly made. The rest of the chapters illustrate the confused nature of the war and the often-precarious condition of the respective armies. Even specialists in Polish history, for example, may be surprised by the difficulty that the Polish state faced in raising and retaining soldiers. Ultimately, Górny writes, that Polish victory was due as much to Polish strength as to Bolshevik weakness (which is true of every battle in every war that has ever been fought).

Ultimately this book displays both the strengths and weaknesses of the polemical genre. Górny deserves his reputation as a first-rate historian, and specialists and interested general readers of a contrarian bent will enjoy his lively and incisive attacks on conventional wisdom. At the same time, those without a broader knowledge of the period (such as lower-level undergraduate students) might be ill-served by it. For example, Górny is right to emphasize the often-shambolic condition of the Red Army; yet it is also important to know that this army had inflicted serious defeats upon its enemies in a vast and sprawling civil war. It was reasonable to be terrified as it drove into the new Polish state. Similarly, excessive scepticism can generate its own dogmas. Particularly after some of the failed nation-building ventures over the past few decades, the Polish state’s ability to create functioning institutions, including an army, from the wreckage of the pre-1914 world cannot simply be waved away as nothing exceptional. Or, rather, to both agree with but reframe one of Górny’s central points: what Poland and the other successor states of post-1918 central Europe managed to create was collectively remarkable. It deserves a fresh look, rejecting nationalist-romantic myths but acknowledging that the on-the-ground messiness makes the entire period more, not less, compelling, and the various political successes more, not less, difficult to explain. Górny insists that and honest reckoning with the region’s past is needed “because there are no miracles” (p. 9). But, as C.S. Lewis once observed on that subject, “nothing can seem extraordinary until you have discovered what is ordinary.”

Jesse Kauffman is Professor of History at Eastern Michigan University. His first book, Elusive Alliance, a study of the German occupation of Poland in World War One, was published in 2015 by Harvard University Press. He is currently finishing his second book, an analysis of the war’s so-called eastern Front, tentatively entitled Blood Dimmed Tide: Central Europe’s Long Great War, 1905-1921, which will also be published by Harvard.