Different from the others: queer mobilization before Stonewall

Published by: McGill-Queen’s University Press

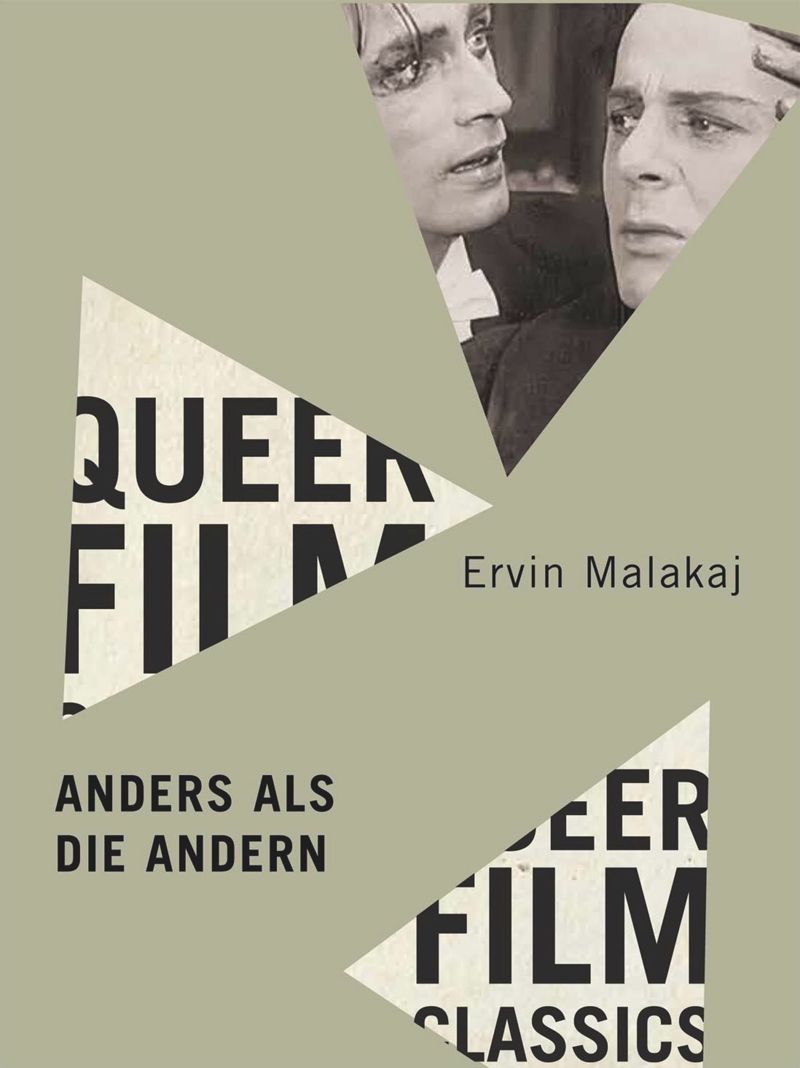

Ervin Malakaj’s Anders Als die Andern is a study of the Weimar-era film with which it shares its title, directed by Richard Oswald and made in collaboration with sexologist and homosexual rights activist Magnus Hirschfeld, first released in 1919. In writing this volume, Malakaj aims to shed light on queer histories and mobilizations before Stonewall and to interrogate their resonance for queer viewers in the present. The study focuses on the film’s negative emotions and mournful energies: the main character, Körner, a successful musician initially happily in love with another man, commits suicide after he is blackmailed and condemned under Paragraph 175 which criminalized male homosexuality in Germany. At the same time, Malakaj intervenes in discussions among queer scholars and activists, making a convincing case for the shortcomings of affirmative histories of queer lives and progress narratives, and for the continued necessity of engaging with painful queer histories.

In the first chapter, Malakaj retraces Anders als die Andern’s making and its contemporary reception. The film was partly conceived as a social hygiene project and was made in collaboration with the scientist and medical practitioner Magnus Hirschfeld, who aimed to educate wider audiences on the naturalness of homosexuality and the tragic consequences of repression. Turning to film, an increasingly popular medium, the makers of Anders als die Andern adopted the codes of melodrama in an attempt to make the subject matter more relatable to viewers, as the genre evokes daily life and concerns, albeit in a heightened form. Here, Malakaj also delves into the film’s hostile reception and the censorship it faced, largely explained by a rising climate of ethnonationalism and antisemitism in Germany at the time, which also translated into anti-queerness due to anxieties around “German” masculinity and family values.

Malakaj convincingly argues that moments of queer joy in the film only offer temporary respite rather than resolution, and in fact heighten the suffering which inevitably follows them.

In the second chapter, Malakaj engages in more depth with melodrama as a genre, arguing that melodramatic sentimentality can bring visibility to social problems and foster intimate connections between audiences and the issues embodied on the screen – in this case, the plight of a homosexual man in a society where sexual intimacy between men was criminalized. Crucially, Malakaj, borrowing from film studies scholarship, shows that the genre typically did not offer to resolve the issues it brought to light, suggesting instead the impossibility of straightforward solutions to complex pains and social injustice. Malakaj convincingly argues that moments of queer joy in the film only offer temporary respite rather than resolution, and in fact heighten the suffering which inevitably follows them. Moments of joy are not enough to stop the protagonist’s visible bodily decay; a response to the world’s relentless hostility to his queerness. Ultimately, suffering spills into even the film’s most hopeful moments, including a speech by Hirschfeld, set at Körner’s wake, encouraging those in attendance, and indirectly the film’s audience, to resist despair and instead fight for positive change and the end of anti-queer repression. The presence of Körner’s dead body in this scene is a sharp reminder that even such a rousing moment cannot undo the loss occasioned by homophobic violence; that queer pain lingers.

The final chapter turns to the present: in a moving account of his own experience with queer joy and negativity, Malakaj analyses his younger escapades into queer joy, especially through nightlife, as themselves a response to the hostility of the world outside and an avoidance of this painful realization. “Chasing joy alone in a world heavily equipped to harm your comrades”, he adds, “means not taking seriously their (and by extension your) plight” (p. 129). While this account will no doubt resonate with many, activist investment in nightclubs suggests these spaces can offer more than individualized escapism, as do the experiences of community building through them. This includes a context of loss such as the Covid pandemic, as research on initiatives to sustain London’s queer nightlife in that period exemplifies.1 The extent to which queer nightlife is characterized by hedonistic pleasure can also be questioned: is there not, in recent queer anthems, as much to dance to as there is to cry to? Take queer pop phenomenon Chappell Roan and her tale of going against a conservative, rural family’s wishes to dance in the queer “Pink Pony Club”. While the track is in some ways celebratory, the loss of a home and the violence of “screams” condemning her life choices linger throughout the song, suggesting that queer clubs too might be a place to experience negative sentimentality alongside joy, and to collectively reckon with pains that cannot be easily solved, as Malakaj encourages us to do.

in a moving account of his own experience with queer joy and negativity, Malakaj analyses his younger escapades into queer joy, especially through nightlife

Malakaj suggests that negative feelings can offer an alternative to solitary cycles of pleasure though avoidance of the world and disillusion when facing it. Pain that cannot be resolved or made useful still has generative potential, he argues, in that it can provide emotional anchoring to those familiar with feeling negatively in the world and help us to form a more realistic understanding of queer experiences both in the past and in the present. Through an engagement with queer suffering, we are bound to acknowledge both the impossibility of going back into the past and changing it to give figures like Körner happier endings, and the ongoing harm to queer people. Not turning our backs on negative feelings also enables us to mourn, and in so doing, to establish links with others engaged in similar pains and struggles for emancipation, opening possibilities for intergenerational connections between, in this case, queer subjects in Weimar-era Germany and queer subjects in the present. The question of the participation of the dead in this intergenerational community remains open, and one wonders at times if the nuanced account of the film’s enduring relevance in the present obscures the specificities of its relations to queers in the past, whose lives off the screen, largely unknown to us, may well have significantly diverged from elements of continuity centered in Malakaj’s analysis.

In dialogue with historian Heather Love’s explorations of negative emotions in queer cultures,2 Malakaj’s reading of the film offers a compelling third way to both utopian and future-oriented queer theories, such as José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia,3 or – though he does not explicitly engage with this – to an understanding of queerness as only capable of disturbing politics, not producing them, such as formulated in Lee Edelman’s No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive.4 Malakaj’s analysis of Anders als die Andern through the lens of negative feelings, loss and mourning, or “feeling backward”, in Love’s terminology, proposes instead not only that there can be some solace for queer individuals in reckoning with loss, but that queer politics and solidarities can be founded upon it, alongside more utopian projections.

One could reproach Malakaj for falling into the pitfall identified by Love of recuperating negative feelings and transforming them into something productive. Yet he is careful in making a case for the generative potential of queer mourning to go along with the negativity, rather than seeking to overcome it. If it is recuperated in the sense of being made useful to queer politics, suffering in this volume is recuperated on its own terms, as queer suffering, rather than avoided or transfigured into joy or hope.

Giselle Bernard is a Ph.D. researcher at the History Department of the European University Institute (EUI) in Fiesole, Italy. Her work focuses on European women desiring women and the role their encounters with spaces they imagined as “oriental” played in shaping subjectivities based on same-gender sexualities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Before coming to the EUI, she completed her first master’s degree in migration studies at the University of Oxford and another in European history at Humboldt University in Berlin.

1 Mark McCormack and Fiona Measham, ‘Building a Sustainable Queer Nightlife in London: Queer Creatives, COVID-19 and Community in the Capital’, 2022, https://research.aston.ac.uk/files/153258945/LondonQueerNightlife_v7_High_res.pdf.

2 Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge, Massachusetts; Harvard University Press, 2007).

3 José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, 10th anniversary edition, revised edition, Sexual Cultures (New York: New York University Press, 2019).

4 Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004).