Examining Hana Ponická's dissent and poetry

Published by: ibidem Press

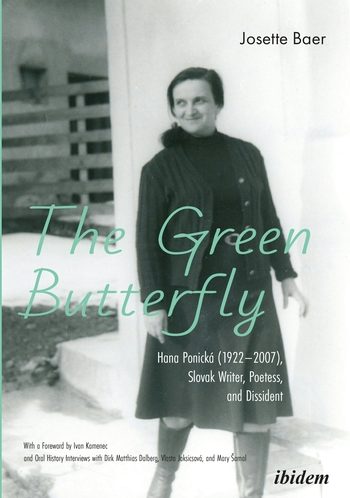

While Czech dissidents such as Václav Havel and Ludvík Vaculík captured Western attention from the first appearance of their Charter 77 manifesto in 1977 and have enjoyed considerable scholarly attention in the decades since, female dissidents have remained largely in the shadows, and the much smaller Slovak dissident movement has been almost entirely overlooked. Josette Baer’s new study of Hana Ponická, the best-known Slovak woman dissident, fills an important gap in English-language research on the late socialist period, although with somewhat mixed results. Ponická was the author of Lukavické zápisky (here referred to as Notes from Lukavica and also known as The Lukavica Notebooks), which she wrote in 1977 while living in an old mill in the Slovak village of Lukavica and which is now considered one of the most notable works of 1970s Slovak literature. Baer’s monograph, The Green Butterfly, consists of three main chapters: one covering Ponická’s early life until the mid-1970s; a second examining Lukavické zápisky; and the third discussing her views after 1989. Baer is a political scientist, not a literary historian, and she states in the first chapter that she “cannot delve into Hana’s extensive translations from foreign literature, her children’s books, and poetry. This study is dedicated to her political texts, or rather, texts related to political events.” (p. 40) Nonetheless, any reader familiar with East Central European history is aware that culture in the region can rarely be separated from politics, and doubly so in Czechoslovakia’s post-1968 normalization period.

The Green Butterfly is aimed at readers with a knowledge of the late-socialist conditions in the Eastern Bloc, but some material is provided for those with no background in the field. In addition to Ponická’s newspaper articles, interviews and the Lukavické zápisky, Baer uses materials from the StB (state security, that is the secret police) surveillance files on the dissident author. However, the first chapter does not give a detailed overview of Ponická’s life and career, which is summarized in a paragraph of the introduction (p. 4). Moreover, while Baer’s title comes from a motionless green butterfly that Ponická sees in a glass, which becomes a metaphor for the spirit of freedom she hopes to revive with her work, the significance of this memorable image is not explained until partly through Chapter 2 (p. 67).

The volume also includes a foreword by the Slovak historian Ivan Kamenec, as well as three “oral history interviews”, two with other historians from the Slovak Academy of Sciences, namely Dirk Matthias Dalberg and Vlasta Jaksicsová, and one with the Czech-American historian Mary Hrabik Šamal. While each has interesting personal insights, only the last of these has direct relevance to Ponická.

In her analysis, Baer implicitly compares Ponická to better-known Czech dissidents, concluding that her article about the influential Slovak journal Kultúrny život (whose publication was curtailed after the Soviet occupation) “demonstrates that she was much more interested in literature and culture than politics. She did not demand political rights or criticize the invasion as so many of her colleagues in the Czech part [of Czechoslovakia] did.” (p. 55) However, in this period of rapidly reimposed censorship, even touching on such topics in ambiguous ways was a political and critical act. This relatively short chapter would have benefited from further examples of Ponická’s journalistic writing of the time. The concluding section on her 1974 biography of the artist Janko Novak (a personal friend who was killed in the war), while a potentially fascinating look at the writer’s last officially published book before her dissident period, is also too brief to provide a deeper understanding of her work.

“the courage of a few cannot be silenced with political concrete such as imprisonment, character assassination and psychological terror.”

The most valuable part of The Green Butterfly is the discussion of the Lukavické zápisky, including numerous translated excerpts that have not appeared in English before. Yet despite the work’s “clarity” and “simplicity”, Baer sees it as a text that is “not easy to read” and “beyond the pale of our understanding” for those Western readers who have not experienced life under a Communist regime (p. 65). In the section examining “Nature as allegory for politics”, Baer describes one of the most evocative symbols of Ponická’s narrative, when she returns from Bratislava to find that the stream running behind her house is overflowing with fresh water, thanks to a spring that had accidentally been drilled open by geologists. Unfortunately, considering this natural wonder a threat to nearby well-established spas, the authorities blocked it with stone and concrete, which Baer describes as a clearly political message in Lukavické zápisky: “the courage of a few cannot be silenced with political concrete such as imprisonment, character assassination and psychological terror.” (pp. 99-100) Seeing the spring as an allusion to Charter 77, Baer compares Ponická’s writing (which she claims was inspired directly by nature rather than by philosophers such as Kant) to Havel’s more overtly theoretical approach, implying a contrast between feminine/intuitive and masculine/rational ways of thinking. In the subsequent sections of Chapter 2, Baer discusses a personal attack on Ponická in the newspaper Pravda (which sarcastically called her a “Slovak Joan of Arc” supported by the Czech dissident Vaculík), Ponická’s secret police interrogation as described in chilling detail in Lukavické zápisky, and her trial along with four other dissidents in November 1989, on the verge of the Velvet Revolution.

Chapter 3 gives excerpts from Ponická’s writing in the post-socialist period but, as in the first chapter, these provide an overview rather than an in-depth analysis. The most insightful discussion is in the interview with Mary Hrabik Šamal, who knew Ponická personally and wrote an article on Lukavické zápisky before it was known to most Slovak readers, with another Czech émigré scholar, Zdenka Brodská, Like Baer, Šamal views Ponická’s writing in terms of gender, stating that she “looked at the world from a woman’s point of view,” and also sees her as primarily “concerned with the fate of Slovak culture, [although] she lived in an era when politics and culture were so intertwined that she felt compelled to engage in public affairs.” (p. 183) Perhaps the most enlightening part of their exchange is when Baer asks Šamal why Ponická is “still unknown” compared to Czech dissidents like Jiřina Šiklová and Eva Kantůrková. Šamal suggests that the question itself is somewhat misleading, since Ponická’s dissident activity in Slovakia was both “later” and “smaller in scope” than that of her Czech contemporaries, and that unlike their active participation in the movement, Ponická “sought refuge among the simple folks in the countryside.” (pp. 186-87) Šamal also makes the key point that “Ponická did not sign Charter 77 when it first appeared, although several English language sources claim that she did” (p. 187), further separating her from the better-known narrative of Czech dissidence. While these decisions reflect Ponická’s less politicized personal outlook, they also reveal how isolated Slovak dissident activity was in general, and how much more challenging it was for Slovaks to make even symbolic gestures.

Despite its limitations, Baer’s study of Hana Ponická (which she states is the first in any language) is a notable contribution to the miniscule field of Slovak studies in English (full-length monographs on Central European women writers in general are equally rare.) Her bibliography does not include another English-language study that would have enhanced her analysis: the chapter “Recent Prose of Hana Ponická and Oľga Feldeková: Dissident Autobiography and Aesopian Fiction,” by Norma L. Rudinsky in the 1992 volume edited by Celia Hawkesworth, Literature and Politics in Eastern Europe. One final quibble might be made regarding the author’s use of the dated term “poetess” in the subtitle, as well as in the text, although Ponická’s poetic output only receives a passing mention. As a subtitle, “Slovak Writer and Dissident” would have been perfectly sufficient as a summary of Ponická’s cultural legacy.

Charles Sabatos is a professor at Yeditepe University in Istanbul, where he lectures on American, Slavic, and comparative literature. He is the author of Frontier Orientalism and The Turkish Image in Central European Literature (Lexington Books, 2020). He has also published articles in numerous scholarly journals, as well as translations of contemporary Slovak and Czech writers.