How to break a promise: Ideologies of austerity in Eastern Europe

Published by: Harvard University Press

Scholars in the neoliberal era have often struggled to make sense of a bitter truth: that political authorities are willing and able to impose enormous economic pain on their own constituents. Why would politicians knowingly abdicate their long-term powers of economic governance—and political leverage—to short-term financial interests looking to shock and strip-mine local assets? Typical answers to the austerity problem see it as a strict mandate imposed by international creditors on local officials, who scramble to disguise its harsh effects. Painful structural adjustments are justified not by an overt domestic politics, but through acts of subtle rebranding: transvaluations of values that turn exploitation, poverty and risk into virtues like productivity, thrift and entrepreneurship.

This theory has been widely applied to the post-Soviet and East European cases, where austerity was accompanied by major cultural change. Area studies experts and anthropologists have often framed austerity as a problem of value transfer, searching for techniques of Foucauldian subjectification in the post-89 structural adjustments. Another genre of scholarship—reacting to the resurgence of reactionary politics in Poland and Hungary since the 2010s—emphasizes the failure of value transfer, rather than its success. These accounts highlight the difficulties of achieving disciplined transformations of character by drawing attention to the stubbornness of psychological instincts like resistance to change and ressentiment.

At a certain point, however, it becomes impossible to judge austerity’s lasting ideological power as a matter of subliminal messaging or uninformed instinct. What determines whether psychologies of submission will beat out psychologies of resistance? It may be out of a desire to overcome these intractable lines of questioning that the historian Fritz Bartel sidesteps the shifting landscape of values and instincts, and hones in on some of austerity’s explicit political arguments.

Bartel’s book shows with detailed archival evidence that austerity’s late-twentieth-century architects were neither free-market fanatics without a thought for politics, nor snake-oil salesmen hawking a future of political harmony and austerity-led growth.

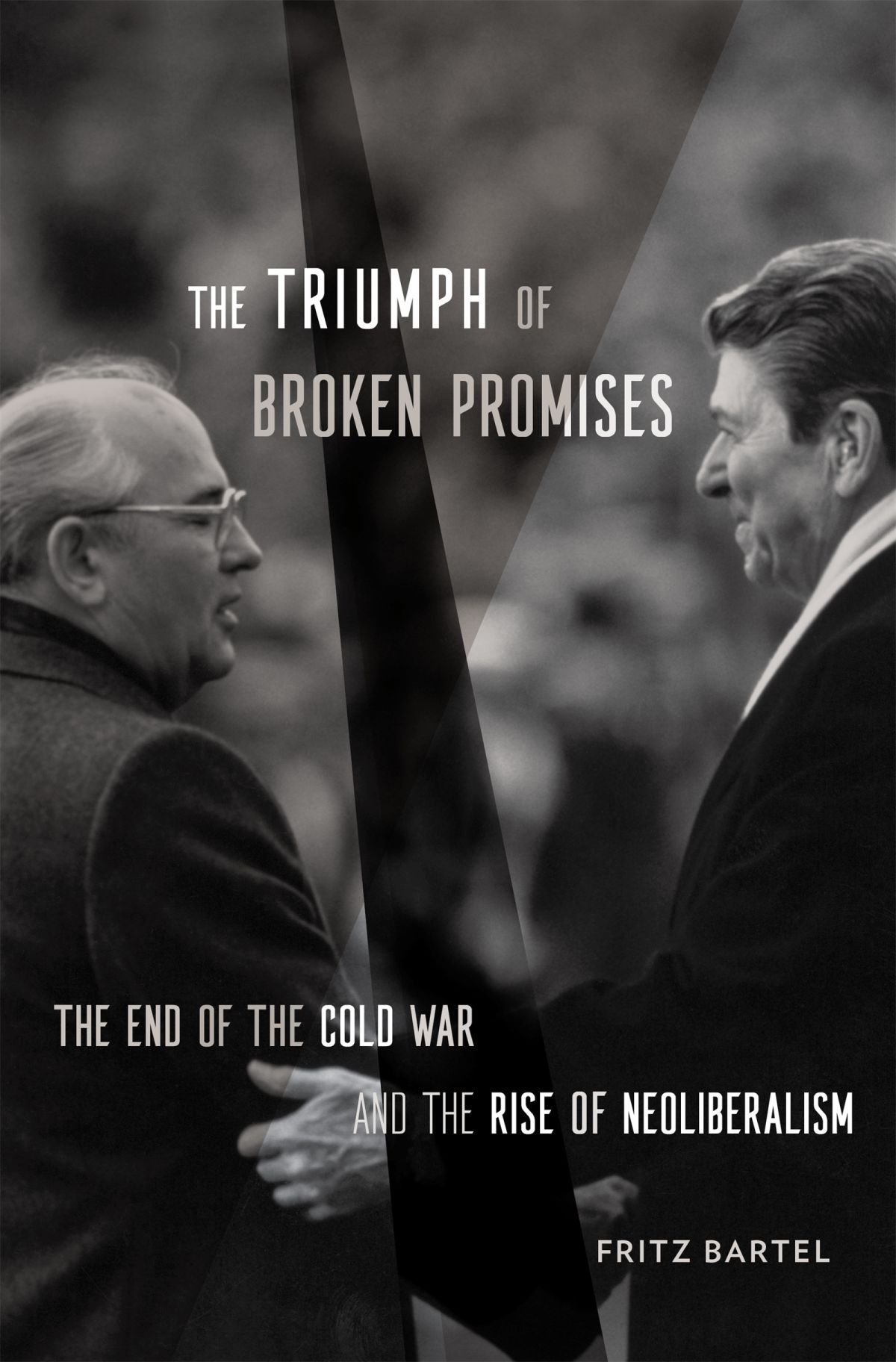

In The Triumph of Broken Promises, Bartel draws our attention to the hard-nosed forms of reasoning used to justify austerity in both the East and the West at the end of the Cold War. His account is refreshing because it sees politicians and even publics as engaged with—and thus also susceptible to—ideas about governance and its limits. Unable to secure the positive identification or personal attachment of anyone but its most extreme adherents, austerity nevertheless made a case for itself by staging empirical arguments about the world as it ostensibly really was: uncompromising and riddled by crisis.

Bartel’s book shows with detailed archival evidence that austerity’s late-twentieth-century architects were neither free-market fanatics without a thought for politics, nor snake-oil salesmen hawking a future of political harmony and austerity-led growth. To the contrary, successful leaders emphasized the difficulties of governing austerity in both political and economic terms. Bartel contrasts Gerald Ford’s failed “Whip Inflation Now” program, which encouraged Americans to “grow their own food, balance their budgets, and use credit sparingly” (p. 34) with Paul Volcker’s austerity strategy, which emphasized grim necessity more than civic virtue. By cynically embracing Milton Friedman’s monetarist philosophy, Volcker buried the federal government’s capabilities under an onslaught of ostensible chaos: the diffuse and unpredictable working of the price mechanism, the irrational ambitions of labor unions and the unpredictable world of geopolitics.

In Great Britain, too, austerity’s most successful ideologists emphasized the image of dire straits over disingenuous promises of a rosy future. To make this point, Bartel zeroes in on Stepping Stones, a report commissioned by Margaret Thatcher in 1977. Although the report’s influence on the Conservative Party would be overshadowed by the wage freezes, work stoppages, and shortages under James Callaghan’s Labour government during the following “Winter of Discontent”, it anticipated the Conversative Party’s winning communications strategy. Rather than put a positive gloss on the pain of austerity measures, Stepping Stones intended to convince the broader public that their future would, by necessity, be a “pretty uncomfortable” one (p. 79).

Yet didn’t broken-promise politics aim precisely at avoiding responsibility for acting on behalf of society as a whole?

Bartel cleverly ties these fresh interpretations of well-known events in the US and UK to the story of austerity in Eastern Europe. Wojciech Jaruzelski, leader of the Polish communist party throughout the 1980s, and his advisor, Polityka editor Mieczysław Rakowski, form the third political pairing of the book. Beginning in the late 1970s the Polish government faced a series of political challenges, including mass protests over rising food prices and the rise of Solidarity, as well as a global credit squeeze and declining energy imports from the Soviet Union. However, neither dictator nor journalist initially sensed that these pressures could be resolved by simply doubling-down on authoritarianism. Instead, Rakowski and Jaruzelski strategized an act of political abdication. In 1979 Rakowski argued that it “was time for the PZPR to enter into a “partnership” with society”. If the Polish communist party could include its prime competitors—chiefly, the Catholic Church and trade unions—in its decision-making, it could also burden them with the “co-responsibility” for “the country’s fate” (p. 84). Jaruzelski, of course, eventually spooked, declaring a state of martial law on December 13, 1981 with Rakowski’s support. But “power sharing” prevailed in 1989 as the strategy for justifying austerity across Eastern Europe.

Here, however, Bartel’s theory of broken-promise politics begins to break down, or at least branch in different directions. In an effort to contrast the successful trajectory of austerity in the US and UK with its early-1980s failure in crisis-wracked Poland, Bartel overemphasizes the role that ostensibly Western social goods played in enabling austerity, and under-commits to the thrust of his own argument. Jaruzelski’s attempt to emphasize government weakness and social divisions failed in communist Poland, according to Bartel, because the communist party hadn’t secured “society’s trust” (p. 86 and 97). Yet didn’t broken-promise politics aim precisely at avoiding responsibility for acting on behalf of society as a whole? At other times Bartel argues that a longer history of “electoral democracy” and a “neoliberal ideology” (pp. 5-6) valorizing hardship gave the West a leg up in the Cold War race to discipline their publics. But this is a return to the enticement theory of austerity, in which elections compensate for economic hardship and people learn to find meaning in suffering.

Ultimately, then, did the politics of broken promises amount to a politics of tradeoffs—the exchange of one good and one way of life for another—or was it an ideology of complete political pessimism? Of course, this may be a false choice. In Eastern Europe, there were real bargains to be had: priceless legal rights were secured during bouts of shock therapy. In other ways, though, Eastern Europe simply received short shrift. As Bartel shows, the “cardinal challenge” of the Cold War did not confront everyone equally. The Soviet Union, with an empire and enormous oil resources of its own, and the United States, which became a sponge in the early 1980s for dollar denominated investments, were able to avoid some of the harms of late Cold War austerity by shifting them onto Eastern Europe.

an important question Bartel’s work raises is why East European states failed to band together in the late 1980s to negotiate better terms for loan repayment.

And yet, another advantage of Bartel’s focus on political strategy is that it points him towards moments of real local choice. In the end, for example, the GDR was more solvent than Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, the head of the state enterprise charged with securing hard currency, had let on. Schalck had concocted this fudge as a way of incentivizing other economic officials to over-accept his efforts to trim the trade deficit. On the other hand, Hungarian officials resisted prescriptions of austerity up until the last minute. In 1986 János Fekete, deputy vice president of the Hungarian National Bank, insisted to a room of IMF officials that, “Severe adjustment programs undermine [countries’] potential for future growth…” (p. 240) In 1987, General Secretary Kádár insisted at a General Committee meeting that he did “not think that [Hungary was] close to insolvency status… Much of this is a dramatization.” (p. 242). Indeed, an important question Bartel’s work raises is why East European states failed to band together in the late 1980s to negotiate better terms for loan repayment. One gets the sense that the losses felt by Eastern Europe at the end of the Cold War were less the mechanical result of objective scarcity or unilateral power relations than the products of political jockeying—and theorizing—about who could (and could not) be forced to act on behalf of others’ well-being.

It is worth paying closer attention, then, to László Kézdi—the ordinary Hungarian pensioner whose open letter to the Ministry of Finance provides the opening anecdote for Bartel’s book. In his letter, Kézdi demands not an end to rising prices but a rope with which to hang himself and thus “lighten the burden on the state budget”. What does his appeal, however facetious in tone, disclose about the ideology of austerity at the end of the Cold War? It is a sense of impossibility, more than anything else: the knowing futility of his request, the absurd accounting of a life’s work, the unworkability of the state budget. As Bartel’s interest in broken promises would suggest, the triumph of austerity in Eastern Europe may have depended more on this sense of political impossibility than on the cheerful acceptance of hardship.

Sinéad Carolan is a PhD candidate at Columbia University. She is currently writing a dissertation about the history of political thought in Hungary, Poland and Yugoslavia after 1956. She is particularly interested in understanding how social scientists in Eastern Europe theorized the crisis of socialism, and came to embrace capitalism by 1989.