Humanitarian aid and philanthropy in interwar Romania

Published by: Stanford University Press

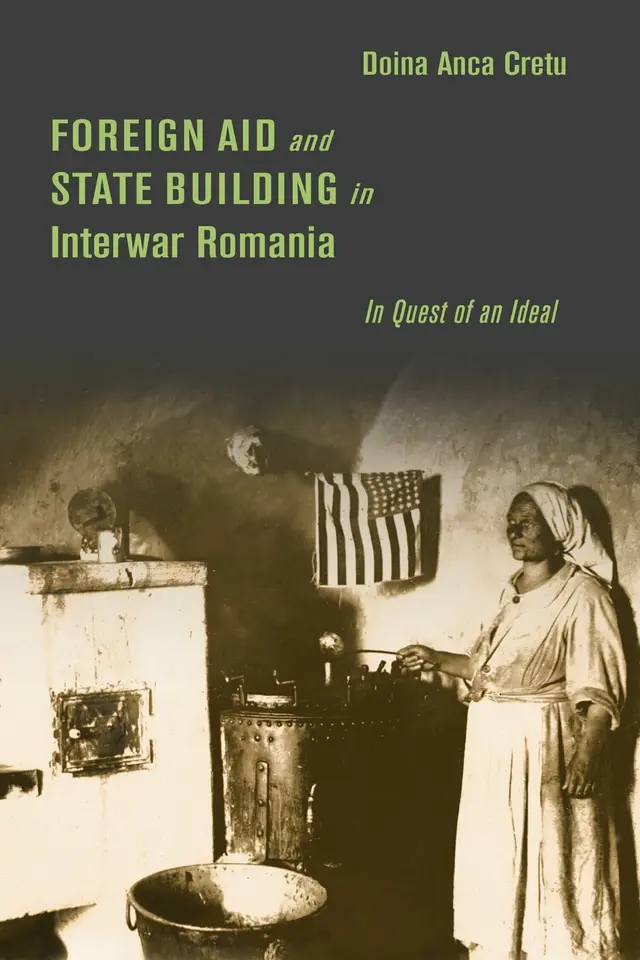

Doina Anca Cretu’s Foreign Aid and State Building in Interwar Romania: In Quest of an Ideal sits at the intersection of a number of overlapping historical fields, advancing each of them: interwar Romania of course, but also the history of American aid in the interwar period, nation-building in Eastern Europe, the role of non-state actors in driving American foreign policy, and the development of Romanian nationalism.

Cretu’s main argument is that international aid to Romania from the United States and/or organizations based in the United States played an important role in the politics of interwar Romania. Romania was a surprisingly large recipient of foreign aid and attention from American humanitarian interests, being seen by Americans as the exemplary case of an underdeveloped and war-devastated Eastern European state. American aid to Romania, as part of the American effort at re-building Europe, was seen to be a test for the ability of America to exert influence abroad and remake the world in its image, as a sign of American power.

Cretu’s book shows us that interwar Romania was not a passive actor on the international stage, nor was it constrained and siloed into merely regional dynamics.

American aid was not unidirectional, however. These aid efforts were taken up by various Romanian politicians and groups for their own domestic agendas. Romanians were not mere recipients and petitioners. Romanians made use of aid from the US to further their own goals, the most overarching being that of building the Romanian state, which had entered a new expanded form at the end of the First World War with the annexations of new territory to the west and north, essentially doubling the state in size. International aid, then, was used as a tool for nationalist ends. American aid became used to advance the cause of Greater Romania. Cretu’s book shows us that interwar Romania was not a passive actor on the international stage, nor was it constrained and siloed into merely regional dynamics. Rather, Romania and a slew of Romanian political actors were engaged in soliciting American support and aid. Cretu looks at the process of American aid-giving through examining the efforts of five major organizations: the American Red Cross, the Junior Red Cross, the American Relief Agency, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, and the Rockefeller Foundation. The book is composed of four chapters, each of which examines a different American aid organization and its interactions with Romanians on the ground. American aid was primarily focused on food aid, childcare and support for war orphans, overall aid to Romanian Jews, particularly those in the newly consolidated Romanian border region of Bessarabia, and public health initiatives and training. Cretu’s research is exhaustive, and in parts even what I would call heroic, digging deeply into the National Archives of Romania, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in the US, the Rockefeller Foundation Archive, and the Joint Distribution Committee Archives.

Cretu’s book is part of the large-scale shift in the historiography of the last decade or so, which is to integrate Eastern European into a global context, showing how the region, commonly thought of as backward, and locally constrained, was in fact deeply imbedded in international politics and processes. While this is partly a shift about historical agency, showing how Eastern Europeans acted upon the world, it is also a shift in structural understandings of 20th-century history. Rather than seeing Eastern Europe as a case example of where things went wrong in history, we see Eastern Europe as the paradigmatic site of the confrontation with modernity.

With Cretu’s work, Romania as the recipient of aid, and the political usages and valences that this aid took on in the country, resembles nothing so much as a standard postcolonial state after the Second World War and its relationship to the politics of American development aid. In this sense, the historiographical stakes go beyond the globalization of Eastern Europe, to the Eastern Europeanization of the globe. While this point goes far beyond what Cretu has researched, her work helps lay the path ahead for it.

One major absence in Cretu’s book is the issue of the western regions taken over by Romania at the end of the First World War, particularly Transylvania and the conflict over it between Romania and Hungary. Given that Romanian political actors made use of American aid for their own state-building agendas, surely, they must have tried to use this aid to consolidate Romanian claims to and control over Transylvania, and to use this aid for development projects in Transylvania, and to combat Hungarian claims. However, Cretu does not address the role of American aid and Romanian actors regarding Transylvania at all. Cretu does focus on American aid efforts and Romanian interlocutors in Bessarabia, especially on the issue of American-Jewish aid to Jewish communities in Bessarabia. Yet, Bessarabia is the only one of the regions annexed, consolidated, and taken over by Romania after the First World Warthat Cretu does examine in detail in terms of aid and state building. We know from Holly Case’s 2010 work Between States: The Transylvanian Question and the European Idea during WWII, that Romania and Hungary both lobbied Nazi Germany to try to get greater control of Transylvania and to advance their territorial claims to the region. Cretu’s work begs the question: was a similar process occurring during the interwar period, in terms of Romania and Hungary making use of American aid to contest their competing claims to Transylvania?

this is an essential work for interwar Eastern European history, while also showing avenues for future scholarship at the most dynamic edges of the field.

Cretu also gestures towards a provocative argument but does not fully spell it out – the interwar connection between American aid to Romania, particularly aid regarding public health, and the rise of fascism and the consolidation of far-right politics in Romania. As Cretu shows, American public health aid to Romania operated in a eugenic mode, focused on ideas of improving the health of the population in order to make the nation strong. This was due to the legacy of the Progressive Era, when public health in the US was formed as a field, in which it was thought that the health of the nation was an outcome of weeding out the weak within the population, aiming for a purified population. To what degree did American aid boost eugenics as a popular discourse in Romania, and thereby contribute to the growth and consolidation of fascism in Romania? This is a key question, towards which Cretu’s book contributes a foundation for approaching, but she herself does not provide an answer. This connects with the well-known work by James Q. Whitman, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law, which showed the influence of American eugenics and Jim Crow laws on Nazi thought and policy, and thereby leads to a larger, field-defining question: what role did American policy, legal precedent, and international aid play in the development and consolidation of fascism across Europe in the interwar period? This is a live question in historical research and is of the utmost political importance.

Cretu’s book could have done with more copyediting, though this is an issue on the editor and publishers’ side, as the book contains numerous grammatical inconsistencies. Overall, this is an essential work for interwar Eastern European history, while also showing avenues for future scholarship at the most dynamic edges of the field.

Mathias Fuelling is a PhD candidate in History at Temple University in Philadelphia. His dissertation is on the dilemmas of economic planning in Czechoslovakia in the 1940s.