It is no longer Greek to us

Published by: Amsterdam University Press

To paraphrase the famous dictum, historical research begins with a wonder. Such a moment of puzzlement occurred to Giedre Mickunaite, art historian and medievalist, professor at the Vilnius Academy of Arts, in 2006 as she studied recently unveiled wall paintings in the parish church of Trakai, Lithuania. What was striking about the murals, was their “Greekness” – the Byzantine origins – which, at first glance, seemed out of place and difficult to contextualize “within any historically and geographically proximate artistic milieu” (p. 18). This perception of a gap forms the basis of Mickunaite’s work. The book is an extended attempt to provide a new framework for understanding the presence and evolving meaning of these Greek images. At the same time, in a microhistorical way, the pieces of art under examination serve as a gateway to narrate broader processes: confessional disputes, ideologies of power, changing artistic tastes, or, finally, cultural transfers that were established beyond the stereotypical East-West or center-peripheries divisions.

What is the maniera graeca in question? One understanding of this term focuses on the geographical origin of an artwork. Either it was created by the Greeks, or in the Greek lands and transferred to Western Europe (mainly Italy) from Constantinople in the aftermath of its sack – firstly by the Crusaders in the thirteenth century, then by the Ottomans in 1453. In Renaissance Italy, art of Greek origins became a subject of discussion and, following Vasari, was defined in opposition to the emerging new Italian style as old, static, and repetitive (p. 19). These definitions, however, are time and place-specific, which establishes a niche for a study on the reception of the Byzantine and post-Byzantine paintings “in Europe’s Catholic East”, where they arrived through the Balkans, Hungary, Ruthenian lands, or Muscovite Rus. Mickunaite then traces in her “object-based study of images [that were] qualified as Greek by their past or present viewers” (p. 18).

Consequently, the “orthodox” style was paradoxically exploited to convey a Catholic message, reflecting the fluidity and entanglement of Christianity at the time and in the region.

The first part of the book, “Silence”, deals with the remnants of the oldest murals from the time of Lithuania’s official Christianisation in the 1380s. To underline their new confessional affiliation, the rulers embellished their residences with Christian paintings. Against the backdrop of other known paintings, the Trakai murals are exceptional. Those in Vilnius, Kreva, and Medininkai, were discovered by archaeologists only 600 years later, from 1985. Besides, they “existed not as wall paintings, but rather as their sketches, copies, descriptions, and photographs” (p. 39). As the political context was crucial for the creation of the paintings, this chapter introduces both the visual materials and the history of Polish-Lithuanian unions and rulers who acted as agents of state transformations and patrons of the arts.

Connecting the dots, Mickunaite argues, the Greek paintings most probably came to Trakai through the Balkans, more precisely Serbia, as indicated by the style, detailing, and arrangement on the wall plane, and the use of Serbian Cyrillic (p. 68-70). During the period of confessional disputes and councils (from Konstanz to Ferrara, Basil, and Florence), these murals elaborated more on the power of the lordship and dukes than on dogmatic ideas. The next chapter narrates the Polish episode of the arrival of “Greek” art. With a much longer Catholic tradition and an established Church administration, the Kingdom of Poland was even less inclined towards or in need of appropriating these paintings. “None of the extant Byzantine murals in Poland occupies the entire interior of a church” (p. 122) – they are located in presbyteries or chapels. The “negotiations”, as this part is titled, between the form and the content were even more evident in Poland than in Lithuania. Consequently, the “orthodox” style was paradoxically exploited to convey a Catholic message, reflecting the fluidity and entanglement of Christianity at the time and in the region. These issues were embodied by Helena, a daughter of Tsar Ivan III and the wife of Prince Alexander Jagiellon, the Great Duke of Lithuania and future king of Poland – despite their marriage, she remained within her creed and this later became the reason to deny her the crown of the Polish queen.

Despite the scarcity of sources, Mickunaite provides an intriguing attempt to track not only the trajectory of artistic motifs and inspirations but also the identity of the painters. Determining who created the murals required an analysis of different kinds of sources. Some of the painters may have arrived in Lithuania with Gregory Tsamblak, a Bulgarian monk who became the Metropolitan of Kyiv and an associate of Prince Vytautas, who pursued a religious union between the Catholic and Orthodox confessions. These plans, however, were not implemented. As Mickunaite sums up the cultural exchange: “Southern minds and skills were exploited, but Orthodoxy was not spread. The South Slavic influence at the Lithuanian grand ducal court remained a side effect of political and missionary activities” (p. 86).

The maniera graeca made a long journey from being perceived as alien or heterodox art to being integrated into mainstream and vernacular religion.

The Ruthenian and Greek painters are, at least partially, traceable thanks to the royal accounts of the Jagiellonian commissions containing records of payments to artists. Although these terms refer to geographical regions, they were often used to denote a person of the Orthodox faith. One such painter was allegedly a certain Hail, who is known from a royal privilege granting land to the Orthodox church in which he served. Though the grant may be a later forgery and Hail’s existence is also doubtful, his case “explains mute paintings employing an alien visual language by providing the story with the actor, who appears as a kind of “great master”, thus satisfying a need of post-Vasarian art history, rather than informing of a medieval past” (p. 150). This example illustrates the need to explain the existence of Greek paintings in the Catholic churches, to translate and adjust Byzantine aesthetics to the context of the new times, especially in the wake of the Reformation and the return of iconoclastic debates.

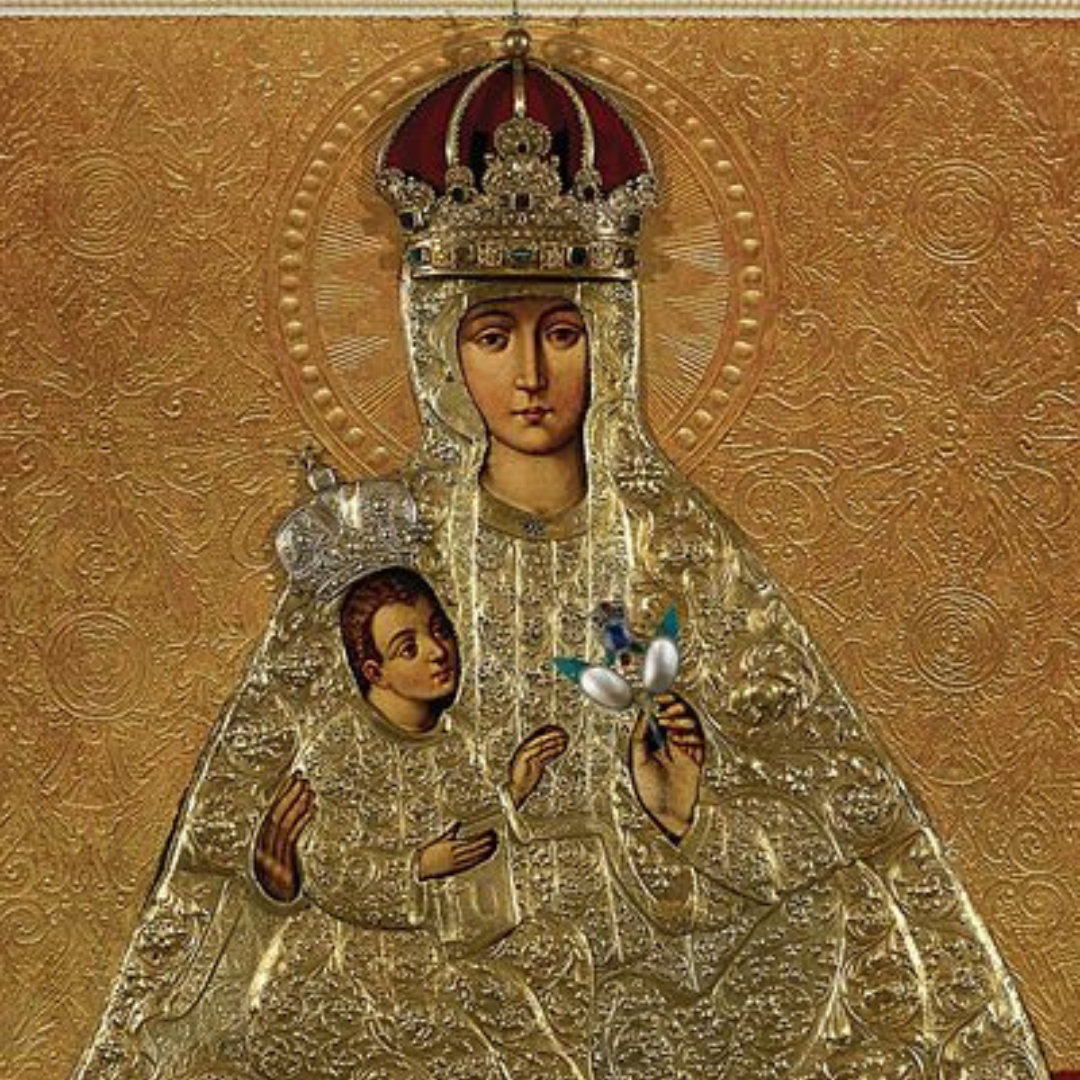

The Catholic Church’s attempts to reinterpret and reintegrate the paintings into the Roman tradition are the main topic of the third part of the book, “Translations”. Trakai is once again the central location, focusing on the icon of Our Lady. It seems that initially the Virgin Mary was depicted in a full-size altar painting which was later cut and repainted to become a portrait that would fit into the post-Trentine Marian devotion. The image, along with historical narratives (e.g. about wars against the Turks) and reports of miracles, was inscribed into a new cosmology of Christianity. This transformation illustrates the evolving Catholic understanding of the time. Mickunaite compares the icons to remembering –the painting “existing here-and-now evokes the distant there-and-then as well as the atemporal beyond-and-ever” (p. 194). While Mickunaite analyzes only one image from Trakai and only briefly mentions the icons of Our Lady of Czestochowa and Vilnius, her argument could be extended to the cult of images in the Commonwealth and Virgin Mary portraits from Polish and Ruthenian lands – Sokal, Lviv, Chełm, Krasnobród, etc. Mickunaite concludes the story of the evolving understanding of the “Greek paintings” with a wave of coronations of the icons, beginning with the coronation of the image of Our Lady of Czestochowa with papal crowns in 1717. The maniera graeca made a long journey from being perceived as alien or heterodox art to being integrated into mainstream and vernacular religion. Yet, their full Catholicization reduced Greekness to a trope testifying to the antiquity of the image.

Jan Blonski is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute (Italy). His research interests encompass various dimensions of popular culture and social relations in the early modern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He published a book on the traditions of miraculous defenses of cities in the south-eastern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Khmelnytskyi uprising (2022).