Left decline and rising populism in Eastern Europe

Published by: Oxford University Press

Discussions about the left’s political retreat have become more frequent during the polycrisis era. This retreat concerns not only its social agenda but also its electoral antagonism with the populist right. Whilst Western Europe continues to attract researchers’ primary focus, the challenge is also to observe the political transformations in postcommunist Europe. Specifically, the way in which postcommunist parties transitioned to democracy created a different idea of what “left” and “right” were in postcommunist countries compared to Western European ideas. Maria Snegovaya approaches the content of “left” and “right” in postcommunist Europe by examining their social bases since the democratic transition and how political fluidity and economic neoliberalism have affected the left’s electoral results. These are some of the points that Snegovaya attempts to cover, as the publication of her book comes during a period of blurred ideological lines for the left and the right’s increased impact at national and European levels.

Snegovaya introduces us to her research by outlining the volume’s structure. As she explains, it is a significant puzzle to understand the similarities between Western European examples and her special interest in class politics. However, Snegovaya’s discussion about demand, supply, and economic versus cultural explanations regarding the shift from the left to the right is crucial, as it creates a more complex framework for the book. This complex framework is based on the author’s general observation that the same political choices that favour populist right parties have damaged the long-term left parties.

Political choices are at the core of party and electoral politics, defining parties’ future and the country’s fate. However, when studied in newly established democracies, such as the postcommunist countries of Europe, they must be observed under the spotlight of radical political decisions. This is why Snegovaya decided to begin her research from the early years of the democratic transition, as she can follow the examined parties in different ideological periods and better present their interactions.

Considering that communist parties transformed into social democratic parties in order to survive, we would expect their relationship with the working class to be extremely close.

In the first chapter, the author traces the line from social democracy’s “Third Way” in Western Europe to its admiration, adaptation and impact on postcommunist left parties. She points out the challenges social democracy faced in Western Europe and how those challenges were transferred to Central and Eastern Europe, considering as milestones the 2004 EU integration and the 2008 economic crisis. This chapter is a perfect step for explaining class politics in the examined area. Considering that communist parties transformed into social democratic parties in order to survive, we would expect their relationship with the working class to be extremely close. However, as Snegovaya explains in the following chapters, this was not how the parties’ relationship with their base continued. The parties built their ideological agenda, turning to the West for examples, and then took an unprecedented turn, focusing on pro-market policies in parallel with their total trust in EU integration. Therefore, during the outbreak of the 2008 economic crisis, the working class was abandoned in the face of new challenges. As Snegovaya mentions, those challenges cover economic and immigration issues, reflecting the discussion in Western Europe during the same period.

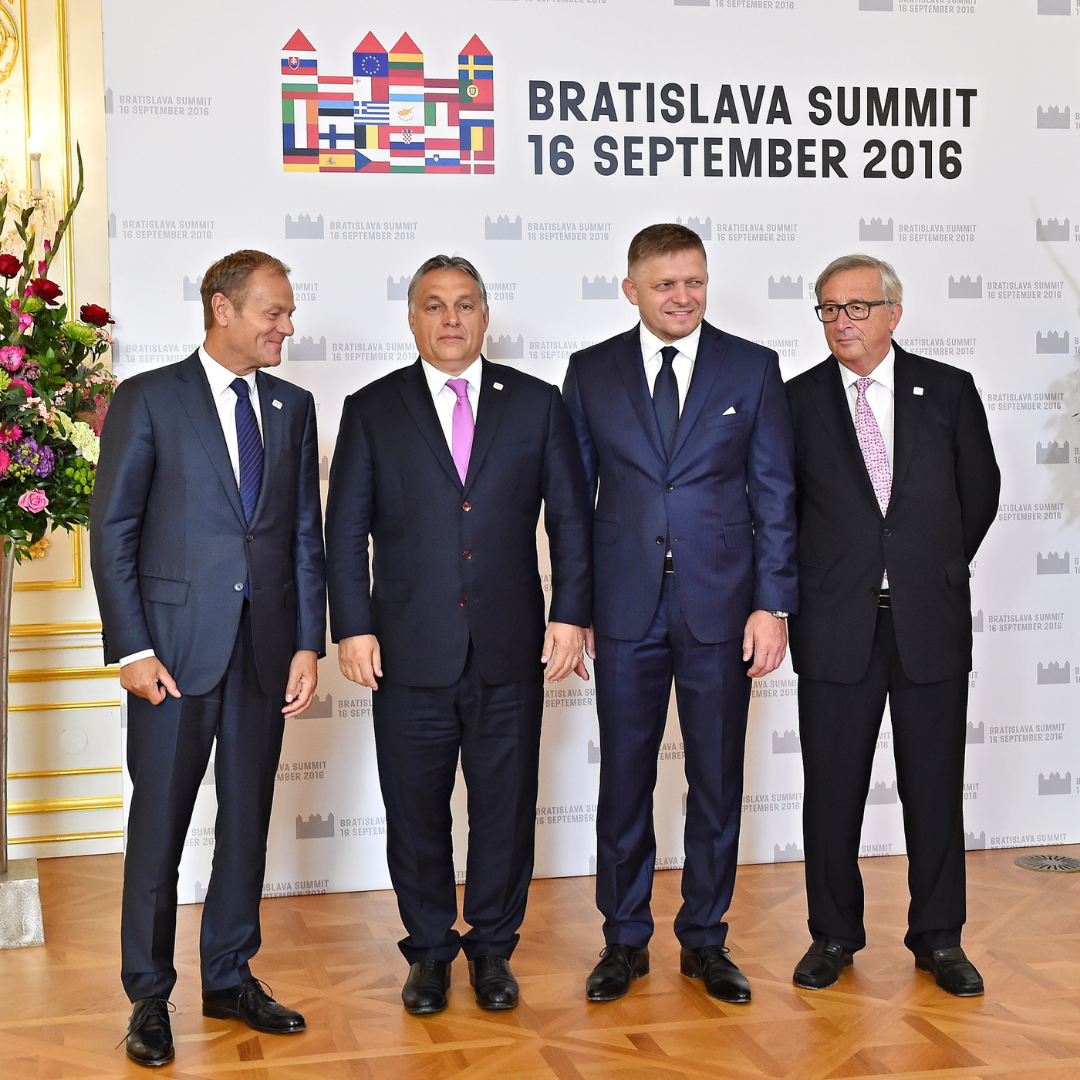

The book focuses on the Visegrad Four: Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Poland. The author acknowledges their dynamic and historical links and builds two cross-country analysis chapters, presenting two countries in each. Snegovaya’s main question is whether the “left” moves towards more right-wing positions. She therefore divides the chapters into the pairs Hungary-Poland and Slovakia-Czech Republic, observing the impact of the left’s movement in more rightward directions. Snegovaya applies a quantitative methodology to achieve these observations, using data from Chapel Hill and the ESS and running several tests to boost her arguments.

When covering the cases of Hungary and Poland, Snegovaya emphasizes the expectations created by the political realignment and how they were never fulfilled, as the left collapsed and retreated in favour of the right. The Chapel Hill Experts Survey is used extensively in this chapter to strengthen the significance of applying individual-level surveys to the research. Due to the different fates that the left parties experienced in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, the emphasis now is on the stability of the alignments and how they benefitted the political scene by avoiding the radical transformations that Hungary and Poland experienced. Again, individual-level surveys appear in every chapter.

The last chapter focuses more on causality. Snegovaya uses experimental surveys to analyse further the impact of the left parties’ movement on the centre-party alignment, acknowledging Hungary as a perfect example of the region. Here the volume’s main structure ends, followed by a significant conclusion and appendices. The conclusion enriches the discussion by pointing out directions in political sociology that could apply to the research presented whilst insisting on the significance of the Eastern European case. In the appendices, the author presents the data she used for the volume, with all the models and statistical tests she ran. Moreover, she includes information about the elite interviews she conducted, underlining the significance of open-access data.

Snegovaya’s work is an important tool for researchers due to its combination of several methodologies, theories, and comparative literature

The book deals with a significant and complex topic: the realignment in new democracies. Snegovaya examines this topic by researching in depth the relationship between the left and the right during specific events. To achieve this, she draws from political sociology, as she applies electoral behaviour when attempting to explain voters’ shifts, parties’ realignment, and the rational choice theory’s impact on specific political environments. Due to the complexity of the theories and the numerous datasets that exist and can accompany them, it is not easy to utilize such a wealth of theories to reflect the political transformations of the examined countries. Snegovaya acknowledges the problem with datasets; hence, she clarifies from the beginning that she is interested in working only with the Chapell Hill Expert Survey and the ESS. As discussed in the appendices, the author ran several statistical tests that support her arguments in the volume. However, she does not depend only on quantitative methods, as she also interviewed several politicians and political officials who were active in the examined period. If we observe the dates of the interviews, some of them were made close to the book’s publication, a significant addition to enriching its content.

Although it is an admirable work and a significant contribution to the field, readers may find the extended historical flashbacks tiring. Snegovaya has a remarkable ability to synthesize and use vast literature for such a work. However, I remain sceptical of the significance of re-reading political events from the early 1990s to explain today’s situation, especially after experiencing a long era of polycrisis since 2008. Snegovaya’s book stops at discussing politics after 2015 (more or less), losing crucial political events that could further expand the book’s central argument. The book offers a sense of incompleteness to the reader, as the reader must imagine what happened in the following years, leaving a significant gap in the literature. Nevertheless, Snegovaya’s work is an important tool for researchers due to its combination of several methodologies, theories, and comparative literature, and for students, as it provides the historical framework of the contemporary Visegrad countries – in a period that remains under the spotlight – and applies several political sociology theories to the field.

George Kordas is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science and History at Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences and an associate at its Centre for Political Research. His research focuses on the comparative study of the far right in Southeastern Europe and the study of the far-right’s subcultures. In his PhD project, he uses qualitative methods to investigate how the discourse of European Parliament members affects European values during the migration and refugee crisis. He has published chapters in international volumes, an article, and several book reviews and review essays in Greek and international journals.