March '68 in Polish cinema

Published by: Universitas

The year 1968 has a special importance in Western and Eastern European history. In Paris, it marked an attempt to overthrow the capitalist order. In Czechoslovakia, it is associated with creating the country’s own path to socialism. In Poland, the year 1968 is more multifaceted. It is a year of student rebellion, the internal conflict in the Polish Workers’ United Party (the PZPR) and the state-sanctioned and sponsored antisemitism, masked as antizionism, following the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. What connects all these events is that after the initial optimism, even euphoria about changing the political and social order, came a comprehensive defeat and disillusionment. This was also the case with Poland, as the title of Maciej Pietrzak’s book indicates.

The meaning and consequences of the events and political and ideological shifts, commonly known as March ‘68, attracted much attention from Polish filmmakers. Pietrzak’s book testifies to this interest, by documenting the signs of March ‘68 in Polish fiction and documentary cinema, from the first such traces to the most recent, at the time of writing of his book. He looks at the double way March ’68 affected Polish cinema: changing its personnel, structure and power relations and the cinematic images of the events. He does it with the thoroughness and precision of a historian, listing the most important events in the history of March ‘68 and its aftermath and pointing to various historical inaccuracies, perpetuated by filmmakers, and with the sensitivity of a film scholar, describing different film techniques, through which they conveyed their truth about this phenomenon. The historical approach is reflected in the structure of the study. It comprises an introduction, sketching the historical context of the March events and two main parts, devoted, respectively, to fiction and documentary cinema.

Pietrzak notes that the most obvious change resulting from March ‘68 was an exodus of Polish filmmakers of Jewish origin, who left Poland to start a life and career in different countries, such as the United States, Denmark and Israel. Among them were Aleksander Ford, one of the most influential people in the Polish film industry in the first two decades after the end of the Second World War, and one of the greatest stars of the 1960s, and Elżbieta Czyżewska, at the time the wife of a Jewish-American journalist, David Halberstam. There were also many documentarists, such as Tadeusz Jaworski, Edward Etler and Marian Marzyński, who left Poland as a result of March ‘68. Their situation after they left Poland is not central to Pietrzak’s research, but it was not very different to that of Czechoslovak filmmakers, who left their country after the Prague Spring, with the vast majority failing to match their success in their own country. One is also tempted to ask what Polish cinema would look like if these people had been able to stay in their country.

the greatest influence of March ’68 was on the generation of filmmakers who created the Cinema of Moral Concern, such as Zanussi, Kieślowski and Kijowski.

Another consequence of March ‘68, which Pietrzak examines thoroughly, was an increased censorship and self-censorship. This affected the scarcity of the straightforward representation of March ‘68 in the immediate period following the events and the oblique ways this event was evoked for a considerable amount of time. At the same time, this obliqueness provided the viewer and, especially, the privileged viewer, the film critic, with an opportunity to search for allusions to March ‘68 buried under the weight of the narratives often set in different places and historical periods. Pietrzak uses this opportunity, offering often original interpretations of many well-known films, which at first glance have nothing in common with March ‘68, such as Samotność we dwoje (Solitude For Two, 1968), directed by Stanisław Różewicz, Diabeł (Devil, 1972), directed by Andrzej Żuławski and Wszystko na sprzedaż (Everything for Sale, 1968), directed by Andrzej Wajda.

As Pietrzak cites references to March ‘68 in plenty of Polish films – especially those created by unquestioned authors of Polish cinema, such as Andrzej Wajda, Stanisław Różewicz, Tadeusz Konwicki, Andrzej Żuławski, Krzysztof Zanussi, Krzysztof Kieślowski, Marek Piwowski, Piotr Szulkin, Janusz Kijowski, and documentarists such as Maria Zmarz-Koczanowicz, Marcel Łoziński and Marian Marzyński – one can treat his book as an alternative history of Polish cinema and a companion piece to those authored by, for example, Tadeusz Lubelski and Paul Coates. That said, one notes that the greatest influence of March ’68 was on the generation of filmmakers who created the Cinema of Moral Concern, such as Zanussi, Kieślowski and Kijowski. This also accounts for a distinct pessimism in their films and scepticism about the possibility of representing reality truthfully.

March ‘68 can be located in the lineage of “Polish months”, such as October 1956 and August 1980. This narrative, ultimately, points to the victory of Polish society over the alien and hostile state.

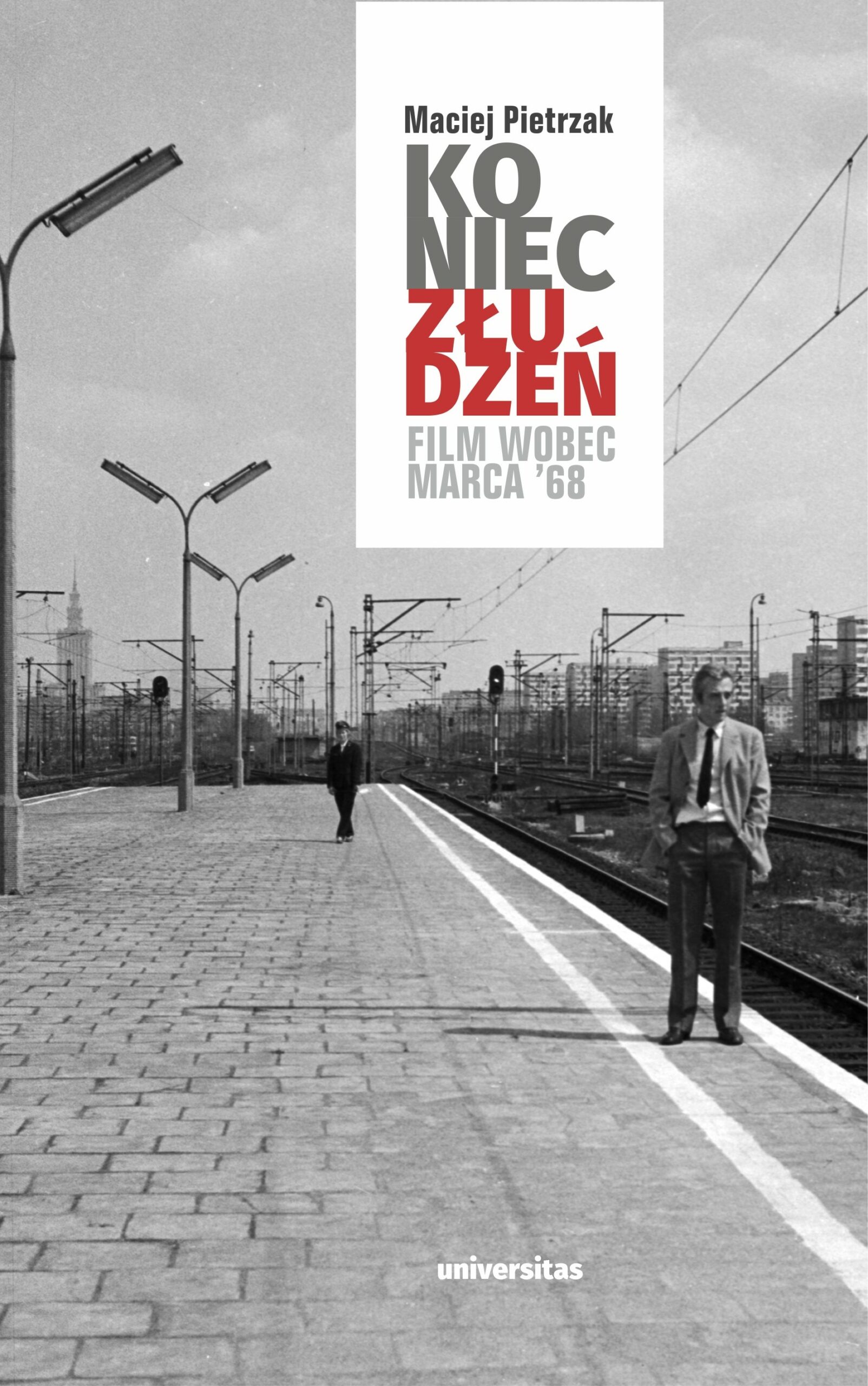

Pietrzak argues, that “March ‘68 cinema”, if we can use such a term, was very versatile in terms of its ideology and genres. Among films tackling this topic we find arthouse and popular films, melodramas, comedies, biopics and even horror movies. Hence, to find their common denominator, we should look rather at certain characteristic visual motifs. He identifies two such motifs of March ‘68 cinema: the courtyard of Warsaw University on Krakowskie Przedmieście Street and the Gdansk railway station in Warsaw. The first is linked to the student protest; the second to the exile of Polish intellectuals and artists, particularly of Jewish background. My slight criticism of Pietrzak’s study is its lack of interest in the sounds of March ’68, even though I believe they were very distinct and many films about this event try to recreate the soundscape of this period, for example the relatively recent Różyczka (The Little Rose, 2010), directed by Jan Kidawa-Błoński. His book thus testifies to the ocularcentrism dominant in Polish film scholarship.

Although March ‘68, as I mentioned, was a multifaceted phenomenon, Pietrzak points to its two main aspects and their filmic representations. One is the rebellion against state socialist oppression. From this perspective, March ‘68 can be located in the lineage of “Polish months”, such as October 1956 and August 1980. This narrative, ultimately, points to the victory of Polish society over the alien and hostile state. This might also be a reason why March ’68 reappears in Polish films, such as Człowiek z żelaza (Man of Iron, 1981) by Andrzej Wajda. The second aspect is the antisemitic actions of the state, which were supported by a significant part of Polish society. The exodus of Jews, following the 1967 war, is a big tragedy and stain on Polish history. As Pietrzak argues, this event attracted less interest from Polish filmmakers and is often a topic of self-representation, as in the documentary film Return to Poland (1981) by Marian Marzyński. The relative scarcity of the role and consequence of antisemitism in the unfolding and aftermath of March ‘68 in Polish cinema is understandable, given that no nation wants to present itself as anything but noble. Yet, it cannot be excused and I compliment Pietrzak for dealing with this issue so thoroughly and honestly. This is even more the case today, when we experience a new wave of antisemitism in Europe and globally. In this sense, Pietrzak’s book is not only a historical book, but also a study which captures well the predicament of European Jews today, given that the conflict in Gaza is used as a means to attack them, both physically, targeting places of worship and cultural centres, and rhetorically, accusing Jews of being guilty of their own tragic predicament, as was also the case in Poland following March ‘68. This is just one reason why I hope to see this book translated into English, so it can reach a wider readership.

Ewa Mazierska is Professor of Film Studies at the University of Central Lancashire, UK. She published over thirty monographs and edited collections on film and popular music, including Polish Estrada Music: Organisation, Stars and Representation (Routledge, 2024), Popular Polish Electronic Music, 1970–2020: Cultural History (Routledge, 2021), Polish Popular Music on Screen (Palgrave, 2021) and Poland Daily: Economy, Work, Consumption and Social Class in Polish Cinema (Berghahn, 2017), and monographs of several directors, such as Roman Polanski, Jerzy Skolimowski and Nanni Moretti. She is the principal editor of Studies in Eastern European Cinema. Her work was translated to over 20 languages. Mazierska’s new project concerns Roman Polanski’s films after The Pianist.