Moscow’s First Hybrid War

Published by: Clio

An astounding novel. A rare find. The unhurried but spell-binding and precise prose, which becomes this roman-fleuve, takes the reader on a trip to a forgotten corner of the communist world, to the Horn of Africa, to the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. At that time, Eritrea was an Ethiopian province, as decided by the United Nation in 1952. In English, novels devoted to Ethiopia are typically authored by émigré Ethiopians or their children, who tend to focus on their family stories. As a backdrop they choose the Second World War, when the country was occupied by the Italians (for instance, in Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King, 2019), or the postwar Empire of Ethiopia (in Abraham Verghese’s Cutting for Stone, 2009). I should also mention Ryszard Kapuściński’s The Emperor (1978), ostensibly about the last years and fall of Haile Selassie, but in reality a parable on the author’s own home country of communist Poland. The 1974 Revolution, which led to the rise of Soviet (Derg, communist) Ethiopia, marks the end of the narrative in the last two of the aforementioned titles. In contrast, Synhaiivsʹkyi – drawing on his own experiences as a Soviet interpreter in Africa – probes into the beginning of the end of communist Ethiopia, treated as an integral part of the Soviet bloc. Communism survived in this African country for two years longer than in Europe, and fell only in 1991 when the system’s ultimate protector, the Soviet Union, broke up. Three decades down the line, these events continue to impact Ethiopian and Eritrean politics and society, including Ethiopia’s 2020 civil war against its northern region of Tigray.

The plot consists of two stories, that of Soviet interpreter and translator Andrii in mid-1980s Ethiopia, and that of Mykyta in Ukraine in 2012. In the wake of his mother’s death, Mykyta is on a quest to discover his true origins, guided by the diary of his biological father, which he discovered among his mother’s belongings. Meanwhile, Andrii as a civilian contractor is on the voyage of his life to Africa, smuggled together with Soviet soldiers, all disguised as Soviet tourists on a cruise liner that sails majestically through the Bosporus and the Suez Canal to the Red Sea. To many of Andrii’s colleagues it is indeed like a pleasure voyage after the gruesome tour of duty in the midst of the murderous Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989). In Ethiopia, Andrii interprets for the Soviet, Ethiopian, Cuban and Polish comrades, hoping to earn enough for an apartment in Kyiv. Soviet planes and helicopters transport grain donated by the West to the mountainous north of the country, from where they also take starving people to Ethiopia’s tropical south. The attempt to alleviate the famine fails, despite the involvement of Mother Theresa and international organizations, alongside western volunteers and governments. To Andrii what is happening in Ethiopia resembles a repeat of the Holodomor, about which he learned from his relatives in whispered conversations, out of earshot of eavesdroppers. He is shocked when his detachment eats until they are full, while outside the perimeter fence starving Ethiopians die and, in desperation, eat the Soviet soldiers’ feces.

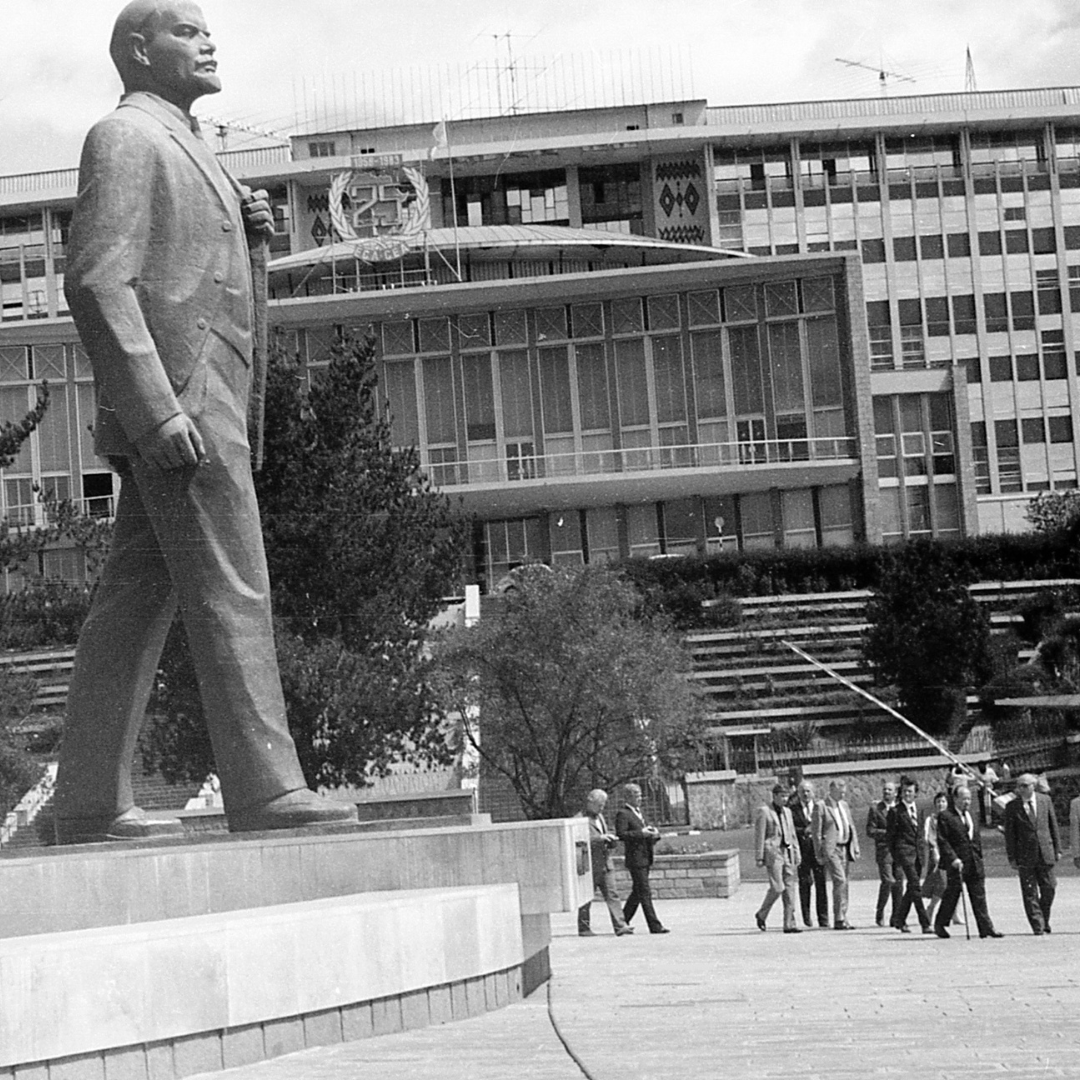

Andrii is tasked with translating the Western press coverage of the Soviet “aid.” Not satisfied with conversations in English, he learns Amharic and picks up Italian to learn more about Ethiopia, its inhabitants and history. He is surprised at how similar the country is to the Soviet Union. The multiethnic population of over 80 nations, complete with their own languages, is ruled over by the three kindred (Semitic) nations of the historical north, namely, the Amharas, Tigrayans and Tigres. In their elevated imperial role these three are similar to the Soviet Union’s Slavic nations of Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians. With time, Andrii notices that the Soviet military busy distributing aid is more like a foreign power surreptitiously engaged in yet another imperial war. After pulling the wool over the eyes of international public opinion by transporting grain and refugees, Soviet planes, helicopters and trucks are sold to the regime’s vast military for a hefty profit. The Tigre-led Eritrean War of Independence (1961-1991) is in full swing, whereas the Tigrayan-led anticommunist guerillas holed up in their underground towns in the mountains stage increasingly successful attacks against the Amhara-led communist regime. The road to peace, to Asmara in the east (or today’s capital of Eritrea), leads westward, to Addis Ababa, where first the communist regime must be defeated.

This is an Ethiopian Holodomor mounted for the sake of starving the Tigrayan and Eritrean partisans and forcing the collectivization (or “villagization,” as the official term is) of the countryside. As many re-settlers to the south die of diseases and due to crop failures in kolkhozes as their starving relatives in the north.

An Amhara friend of Andrii, who passed certain revelatory material to western journalists on the manufactured nature of the famine, disappears along with his family, as though they never existed. A local priest educated in an Orthodox seminary in Leningrad, whom Andrii took to visit, is assassinated as a traitor for his regular contacts with a foreigner. Finally, a Canadian-Ukrainian volunteer, with whom he communicates in his native Ukrainian, confirms Andrii’s suspicions. This is an Ethiopian Holodomor mounted for the sake of starving the Tigrayan and Eritrean partisans and forcing the collectivization (or “villagization,” as the official term is) of the countryside. As many re-settlers to the south die of diseases and due to crop failures in kolkhozes as their starving relatives in the north. Barley sent as aid ends up in a factory producing alcohol, not as food for the starving. But at least the Ethiopian hosts treat the whole detachment to the same meal and entertainment, exposing a festering cleavage between the privileged caste of Soviet officers and the pushed-around privates, especially if they come from Central Asia.

Hunger is the most potent and cheapest weapon of war and of forced social change. Andrii’s detachment is again on the road transporting grain. They notice rogue Ethiopian troops killing a group of villagers and raping women. Driven by human decency and the principles of honor as learned in the military academy, the detachment comes to the rescue. This cathartic event opens the novel’s Part Two. The GRU, or the Soviet military intelligence, concludes that what they had been taught was wrong. It was not the detachment’s role to intervene in the allied army’s operation. Some eggs must be broken in order to make the impatiently expected omelet of communism. The matter is deftly swept under the carpet of Ethiopian-Soviet brotherhood, the soldiers involved are sent home early, while Andrii is made a personal interpreter of the high-ranking intelligence functionary Nef’odov. This functionary is busy making money by selling weaponry on the side, but also continues to spread revolution worldwide. In early January 1986, Nef’odov disappears for good. It later transpires that he is in communist South Yemen, which East German comrades helped to establish. His intervention did not help. The Soviets were unable to stop internecine warfare among the Yemeni communists, during which 0.2% of the country’s population died in less than a fortnight.

Billeted in the compound of Nef’odov’s villa, during the functionary’s frequent absences, Andrii is tasked with accompanying his much younger wife, Irina, to the shops and on pleasure trips. Inevitably, they fall in love. Despite having been married for 15 years, the Nef’odovs are childless. This must have been Nef’odov’s plan from the beginning. A quarter of a century later, Mykyta learns that Andrii was his father and that he had died in an airplane bomb attack. Perhaps, it had been carried out by Eritrean guerillas, enabled by a security breach deliberately allowed by Nef’odov. On this realization, being restored to life in a hospital bed after a vicious attack by the ex-husband of his lover, Nila, Mykyta renounces the life of comfort and fortune made possible by Nef’odov’s shadowy arms deals during the Soviet era and in independent Ukraine. Mykyta wants an honest life and love for his family. He will earn it as a hard-working architect, like the Ukrainians who chose dignity over Russia’s cheap oil in 2004 and again in 2013. Like the Ukrainian pilots who helped the Eritreans in their unequal struggle against Ethiopia (supported by Russian pilots), before Eritrea gained independence in 1993.

Tomasz Kamusella is Reader in Modern History at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. He initiated and co-wrote Eurasian Empires as Blueprints for Ethiopia: From Ethnolinguistic Nation-State to Multiethnic Federation (Routledge 2021). His latest monograph is Politics and the Slavic Languages (Routledge 2021) and he recently co-edited Languages and Nationalism Instead of Empires (Routledge 2023).