Neighbors at the heart of Central Europe

Published by: Verlag Bibliothek der Provinz

Austria and the Czech Republic share a border and a long history, which is the subject of the edited volume Nachbarn: ein österreichisch-tschechisches Geschichtsbuch. Also available in Czech, the book owes its origins to the Conference of Austrian and Czech Historians on Joint Cultural Heritage (SKÖTH), established in 2009. The book comprises thirteen chapters, all jointly written by Austrian and Czech historians. The chapters are both chronological and topical. In addition to the chapters, there are also short essays, often at the end of a chapter, that analyze in depth topics of relevance. The volume is intended for an interested general public in both countries. The book is a narrow history of Austria and the Czech Republic within today’s boundaries. It covers the history of the Bohemian Lands, which are approximately today’s Czech Republic, but it does not, for example, include Slovakia.

The editors point out that despite being neighbors, the sense of neighborliness between the two countries was lost during the last century. Yet, the two countries continue to share economic, social, and cultural ties. In a book that largely focuses on history of the twentieth century, the authors analyze both the interactions between the two countries and the ways in which their individual histories diverge.

The book’s first two chapters survey the two countries shared cultural, economic, political, and social history from the Middle Ages to the eve of the First World War. Though national conflict increased in the Habsburg Monarchy’s final decades, Czech and German speakers still lived together as neighbors, sometimes exchanging children between Czech- and German-speaking households in the Bohemian Lands and even across the Lower Austrian-Bohemian border in order to learn their neighbor’s language.

The book contains several brief essays detailing various points of comparison. The first brief section not included in the book’s table of contents, “The Czech Ethnic Group in Austria,” follows. It reminds readers that while it is difficult to determine exact numbers, many people in Austria today have Czech ancestry. In the Habsburg Monarchy’s final decades, many Czechs (and Slovaks) moved to Vienna and other Austrian provinces so that by 1900, some 100,000 people who employed Czech or Slovak as their language of everyday use lived in Vienna. Though the number of those in Austria with Czech background has fluctuated over time, the number has increased with new Czech migration since 1989.

The third chapter details the downfall of the Monarchy during the First World War and the deterioration of the relationship between Czechs and Germans during the conflict. The following chapter on the interwar period analyzes the formation of the new Austrian and Czechoslovak states. The authors address the issues of drawing new borders, the identities and symbols of the new states, and the economic crisis of the late 1920s and 1930s.

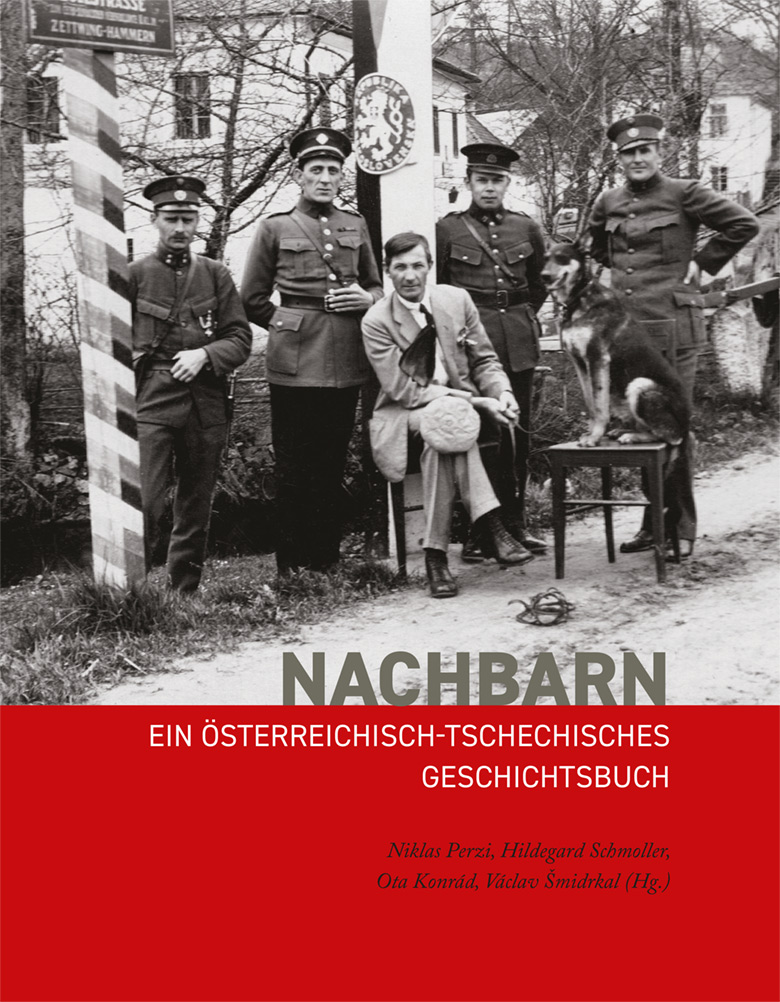

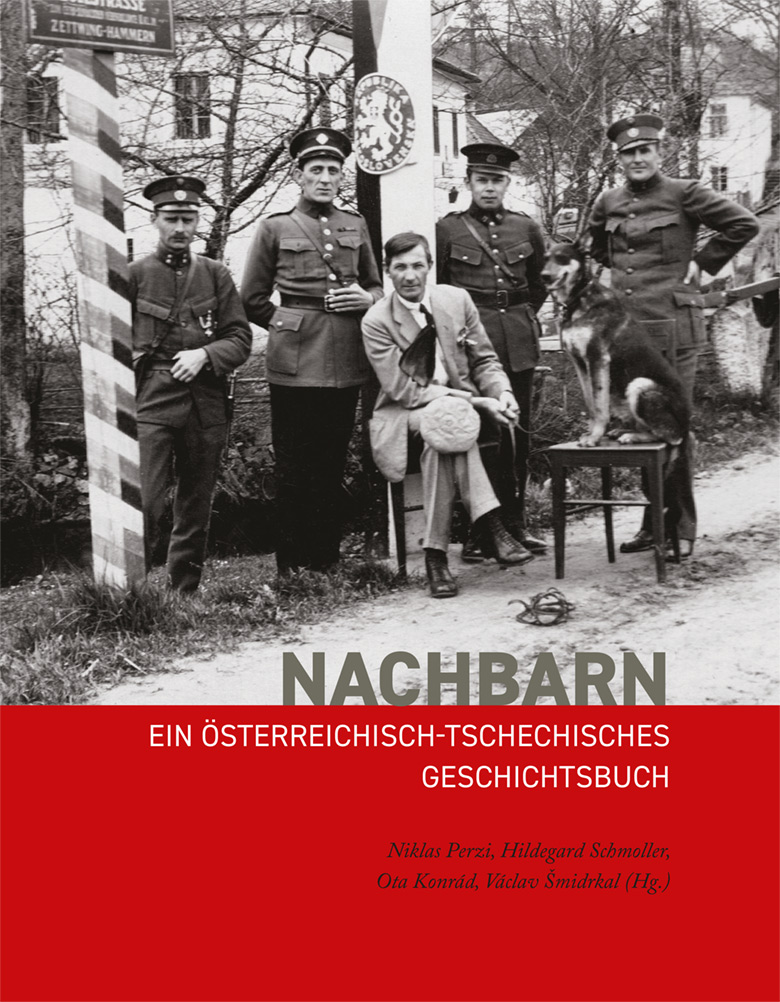

The fifth chapter “Life on the Border—Life with the Border,” the first of two chapters in the book focusing narrowly on the Austrian-Czech border, returns to the creation of the Austro-Czech border in the aftermath of the First World War, tracing everyday life and border crossings through the interwar period. The sixth—also topical—chapter, “With United Arts: Cultural Relations of Austrian and Bohemian-Moravian Lands between 1775 and 1945,” is a brief cultural survey that abruptly jumps back in time. It pays attention to similarities as well as points of exchange and collaboration between Czech and German speakers. The authors remind the reader that Vienna has long been a center of Slavic Studies: Indeed, the world’s first university chair for teaching the Czech language was established at the University of Vienna in 1775, followed by a chair in Prague in 1793.

The seventh—chronological—chapter traces the history of Austria and the Bohemian Lands during the Nazi period, 1938-1945. It provides a detailed description of differences in experiences between Austrian and Sudeten Germans—those Germans living the in Bohemian Lands—and Czechs that would last for decades. During the Second World War, these racial distinctions resulted in different wartime experiences as Austrians and Sudeten Germans were considered part of the Nazis’ Volksgemeinschaft, or people’s community. This chapter on the Nazi period integrates both Czech and German experiences, demonstrating how the events of this period ended any chance at coexistence among Czechs, Germans, and Jews.

Three subsequent chapters detail the growing distance between Czechoslovakia and Austria during the Cold War as both states faced new beginnings after 1945. The immediate postwar period saw the expulsion of some three million Sudeten Germans from Czechoslovakia, including 250,000 who initially went to Austria, where the locals did not welcome them. By the end of the 1940s, Allied-occupied Austria and Czechoslovakia found themselves on different sides of the Iron Curtain, and systematic differences remained for decades.

A final chapter on the history of the two countries traces their history from the late 1980s as both Austria and Czechoslovakia, after 1992, the Czech Republic, became more integrated with the west. And yet, the two have not achieved consensus on issues such as the Beneš Decrees, which provided the legal basis for the expulsion of Germans after the Second World War and the seizure of their property, and the Czechs’ Temelín nuclear power plant, which has been the subject of environmental protests in Austria since the 1980s.

More recently an Austrian mayor refused to visit Tabor/Tábor, a town the Hussites founded, on the grounds that his own town had been attacked by Hussites some 570 years earlier.

The two topical chapters between the interwar period and the onset of the Second World War interrupt the chronological narrative, and the same narrative is again interrupted at the end of the book with two chapters that discuss borders and stereotypes, respectively. While these chapters are interesting and useful, they needed to be better integrated into the chronological narrative. The second chapter titled “Life on the border—Life with the Border” (Chapter 12) starts with the Nazi period moving through the early aughts of this century. It includes the Czech Republic’s accession to the European Union in 2004 and its incorporation in the Schengen Area in 2007. In addition to providing more detail on the Sudeten crisis of 1938, the subsequent Nazi occupation, and wartime resistance, the chapter also assesses the postwar expulsion of the Germans. Living behind the Iron Curtain, those Czechs on the border came directly into contact with politics, in particular, the depopulation of the border region in the 1950s following the creation of a border strip and the demolition of villages on the Czechoslovak side. However, post 1989, the opening of the Austrian-Czech border has led to new connections and partnerships.

The book’s final, also topical, chapter discusses stereotypes, focusing on the ways in which Czechs and Austrians have viewed their neighbors. Starting during the Habsburg Monarchy, the authors trace their changing attitudes to the present. One Austrian stereotype of the Czechs is that of the heretical Hussite. In the nineteenth century, a counting rhyme mentioned that bad children would be snatched by the “Hussites.” Later in the 1930s, Sudeten German leader Konrad Henlein sought to rally Sudeten Germans with references to the “Hussite-Bolshevik criminals in Prague.” More recently an Austrian mayor refused to visit Tabor/Tábor, a town the Hussites founded, on the grounds that his own town had been attacked by Hussites some 570 years earlier. Czechs have long associated their defeat at the Battle of White Mountain in 1620 with Habsburg Germanization and re-Catholicization. During the nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries, the Czechs viewed the Hussites positively while White Mountain symbolized tragedy for the Czech nation and termed the period that followed the time of “darkness” (temno). The positive view of Hussitism played an important part in the creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918. The communists also considered White Mountain a turning point in Czech history. While not as prominent in the twenty-first century, references to White Mountain and the Hussite past continue.

The events of 1989 have allowed the two countries to build a new relationship; however, points of tension remain. While Czechs tend to see their neighbor positively, that is less true for Austrians viewing their neighbor. The complicated relationship between these neighboring states suggests the value of this kind of text, which provides a balanced and integrated history of their shared past as well as points of divergence. The edited volume—which includes a wide array of illustrations, including lithographs, paintings, maps, photographs, posters, and picture postcards—provides an excellent synthesis of the shared and divergent histories of Austria and the Czech Republic for a general audience.

Kathryn Densford earned her Ph.D. in history from George Washington University. She is currently a Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow at the University of Nevada-Reno. Her research focuses on the Habsburg Monarchy and its successor states. She is working on a book manuscript tentatively titled Beyond the Battlefield: The Provincial Austrian Home Front during the First World War.

Nachbarn: ein österreichisch-tschechisches Geschichtsbuch [Neighbors: an Austrian-Czech history book]

Published by: Verlag Bibliothek der Provinz