New perspectives on Jewish lives under Communism

Published by: Rutgers University Press

Jewish Lives under Communism aims to reexamine Cold War-era stereotypes of the Jews of the Communist Bloc, including the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the German Democratic Republic (the GDR). Over the decades, scholars have tended to stress the “atomization” of these Jews, treating them mostly as objects of state policy and underscoring their disconnectedness from Jewish religious values. Conversely, the editors of this volume, Kateřina Čapková and Kamil Kijek, in their analytical introduction and their chapters, examine the agency of the Jews themselves in the postwar period, as do many of the other contributors. Such agency existed, despite the narrowing of the public space of social and cultural life, because of increasing totalitarianism and the promulgation of anti-Jewish socio-cultural policies. The creation of this space, in which both traditional and modern, irreligious Jewish identities could coexist, was facilitated by the absence of total state control over the lives of the populace, and by the desire of the ruling regimes to enhance their international influence. The willingness of the Jews to adapt to the ruling regime did not necessarily cause them to renounce their ethnic identity. Ethnic identity was the key ingredient in the self-identification of people in Eastern Europe. This concept was explicitly included in many official documents. Thus, ethnicity (“nationality”) featured in all the Soviet censuses, and from 1932 it was indicated in the internal passport of every citizen of the USSR.

Thanks to the emergence of new approaches to the life of Jews in the USSR, in studies about the USSR it has become possible to shift the focus from generalities to particularities. Valery Dymshits analyzes the semi-formal alternative Jewish infrastructure that existed within the framework of the so-called “shadow economy” among a segment of provincial Soviet Jewry who were inclined to maintain their religious and ethnic traditions. Their activity is examined within the context of the Jews’ own notions of informal hierarchy and prestige.

Agata Maksimowska’s chapter on the Jews of Birobidzhan is an equally fascinating, albeit not unassailable, contribution to the study of the transformation of traditional behaviors into modern, “Soviet” ones. The author would have benefited from being more skeptical of the claims by residents of Birobidzhan about the total loss of their positive Jewish identity, and about state antisemitism as the major cause of continuing adherence to this identity.

the “Doctors’ plot” – that is, to the first three months of 1953. This “plot” involved the allegation by the Soviet government that nine of the most prestigious Kremlin physicians, most of them Jews, had murdered two of Stalin’s closest aides in the previous years.

Unlike Maksimowska, who analyzes the official “Jewish territory,” Galina Zelenina focuses her attention on Malakhovka, a town in Moscow Oblast that was known as a special Jewish place. Zelenina takes a look at three groups of Jews who, in her opinion, rarely intersected: the local residents who had maintained their traditional or religious environment from prewar times; the Jewish summer residents from Moscow, who refrained from outward manifestations of their Jewish identity; and the activists of the independent Jewish movement.

The chapter by Anna Shternshis is dedicated to the “Doctors’ plot” – that is, to the first three months of 1953. This “plot” involved the allegation by the Soviet government that nine of the most prestigious Kremlin physicians, most of them Jews, had murdered two of Stalin’s closest aides in the previous years. Unlike most works written on this subject, which discuss the antisemitic policies of the state and the aggressive response of the non-Jews, Shternshis’ article focuses on the strategies adopted by the Jewish physicians themselves to cope with this crisis situation. She also shows how, in later interviews, these individuals would underscore their professional superiority as a way of overcoming the old traumas caused by the discriminatory policies of the late Stalinist period.

Unlike the previous four contributors, whose work is based mostly on interviews, Diana Dumitru deals mainly with archival documents. Her chapter examines the interaction between the Jews and the Soviet system in the early postwar period. She tackles the negative attitude of the authorities toward grassroots antisemitism in those years, and discusses the Jews’ heightened sensitivity to their situation, largely as a result of the trauma of the Holocaust.

The question of the interaction between the Jews and the regime is also addressed in Gennady Estraikh’s chapter about the influence of cultural diplomacy on the development of Yiddish-language culture. He examines the relationship between the USSR and the West to see how the Yiddish Soviet intelligentsia used this type of diplomacy to advance its own agenda.

The motif of transnationality is also clearly articulated in the chapter by David Shneer, which is dedicated to the GDR. Shneer discusses the cultural contacts between the Yiddishist Jewish intelligentsia in the GDR and the Yiddishist Communist circles in the West. Thanks to these contacts, East German antifascism, which was one of the key ideological attributes of the new regime, acquired a distinctly “Yiddishist” flavor.

Anna Koch tackles the question of the identity of the Jewish members of the East German Communist elite. For all their stated willingness to adhere to the official definition of a “Jew” (on the basis of religious affiliation), they actually adopted a more complex position when dealing with the subject of the Holocaust, or when called upon to defend Jewish interests. The ethnic identity of these individuals became particularly pronounced in the early 1950s, in the context of the unfolding anti-Zionist campaign.

The need to pay more attention to Jewish agency is articulated in the contributions by Kamil Kijek (on postwar Poland) and Kateřina Čapková (on Czechoslovakia). Kamil Kijek uses the example of the vibrant new community of Jewish immigrants in the small town of Dzierżoniów in Lower Silesia to convincingly refute the claims about the “break” between the Polish Jews and their prewar past. At the same time, he believes that we must not overlook the social restructuring of Polish Jewry in the immediate postwar period, thanks to the new opportunities created by social equality. Like Estraikh and Shneer, Kijek pays particular attention to questions of transnationalism.

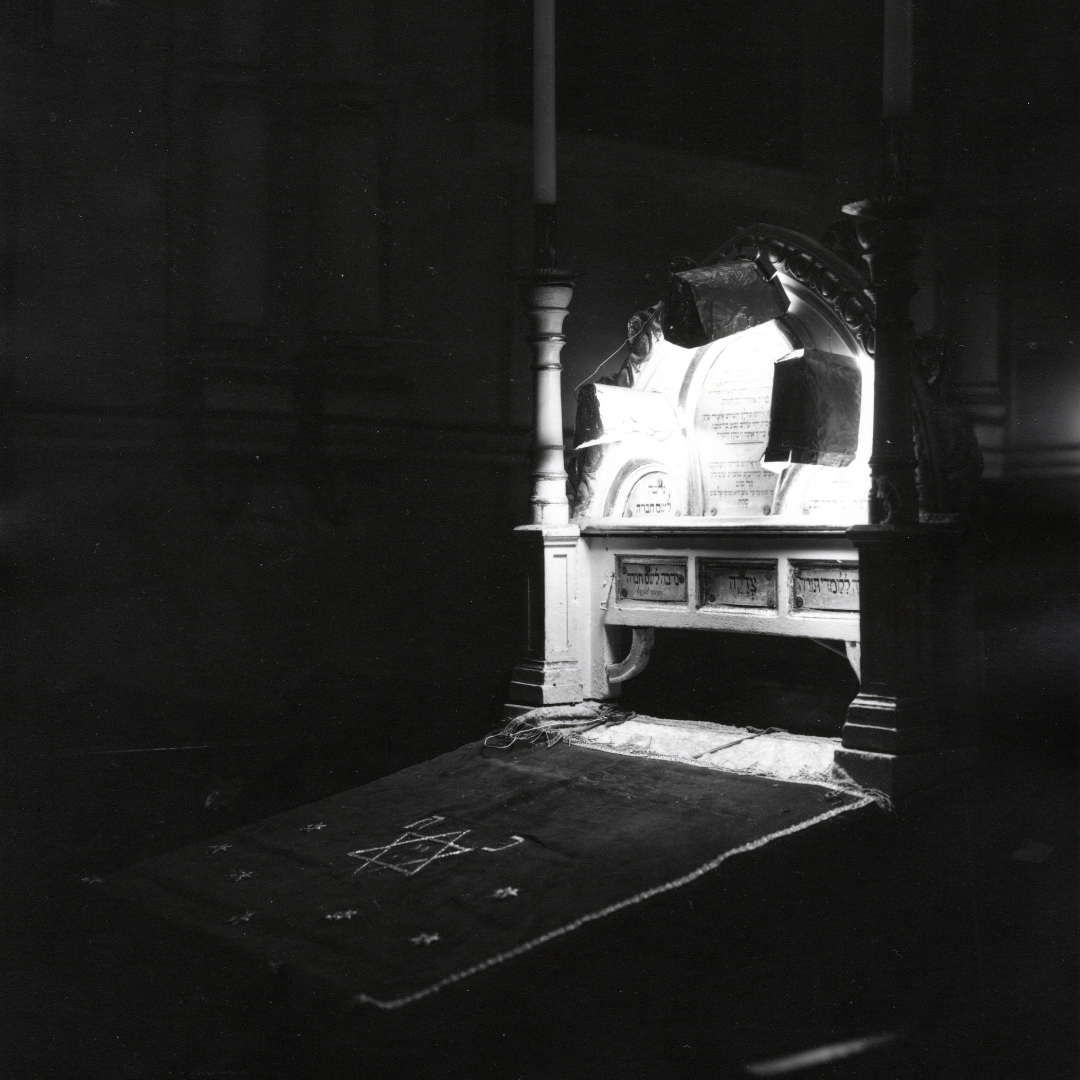

Čapková’s chapter demonstrates the inadequacy of the dominant narrative of the weak Jewish identity of Czechoslovak Jews in the first postwar years. She believes that, apart from the legacy of the Cold War, this perception also stemmed from scholars’ reluctance to recognize differences when comparing the center and the periphery. The Jews of Prague, who have traditionally taken pride of place in academic research, are presented by Čapková as the embodiment of acculturation. Their organized Jewish life was confined to the official framework of religious congregations. In contrast to them, the former Jews of Carpathian Ruthenia embody a different, traditional Jewry, which attempted to reestablish the old forms of communal life outside the boundaries of the state.

The chapter by Marcos Silber explores the adaptation of some Polish Jews to the conditions of immigration to Israel. Silber shows that this movement was not necessarily unidirectional, or colored by Zionist ideology. Some of the migrants moved to Israel and back in accordance with their personal and familial interests, having worked out their own strategy.

Kata Bohus’ chapter analyzes the disagreements between the Hungarian dissidents, who regarded the Jews as a purely religious group, in accordance with the official discourse; and some of the Jewish dissidents, who perceived the “Jewish question” through the more complex, modern prism of ethnic identity.

The uniqueness of this collection goes beyond the willingness of its editors, and many of the contributors, to renounce earlier ideological approaches to the history of Jews in the former Communist states of Europe. The various chapters, which cover a range of countries, enable the authors to bring out the commonalities – and, even more importantly, the differences – between the Jews of those countries.

Dr. Arkadi Zeltser is currently the Director of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union at the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. He is author of The Jews of the Soviet Provinces: Vitebsk and the Shtetls 1917 – 1941, which was published in Russian in 2006 and Unwelcome Memory: Holocaust Monuments in the Soviet Union, published by Yad Vashem in 2018. He is also the editor of a collection of letters entitled To Pour Out My Bitter Soul: Letters form the USSR 1941–1945 and co-editor of collection of articles Distrust, Animosity, and Solidarity: Jews and Non-Jews during the Holocaust in the USSR, both published by Yad Vashem in 2016 and in 2021 respectively.