Reintegrating Czechoslovakia’s Jewish survivors after the Holocaust

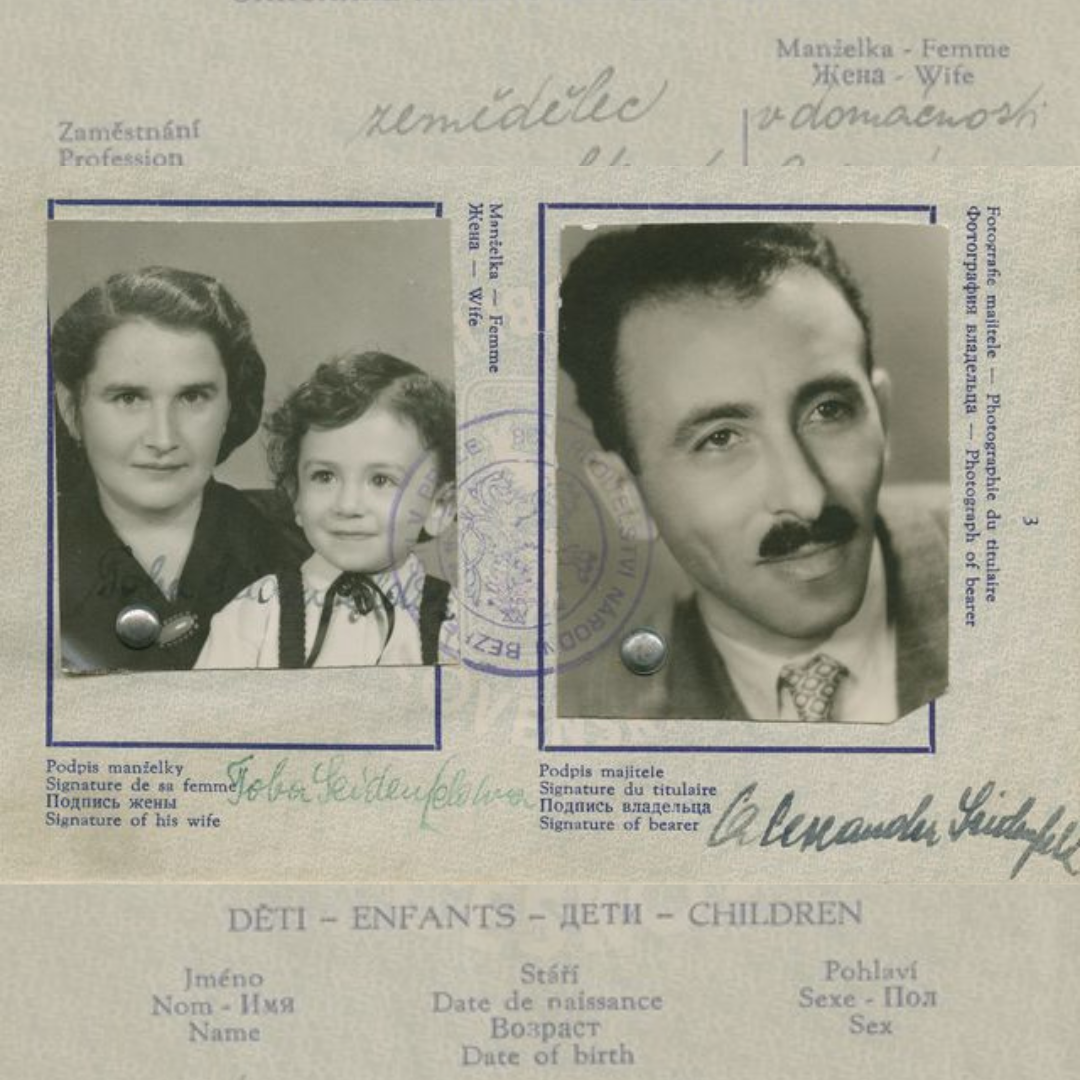

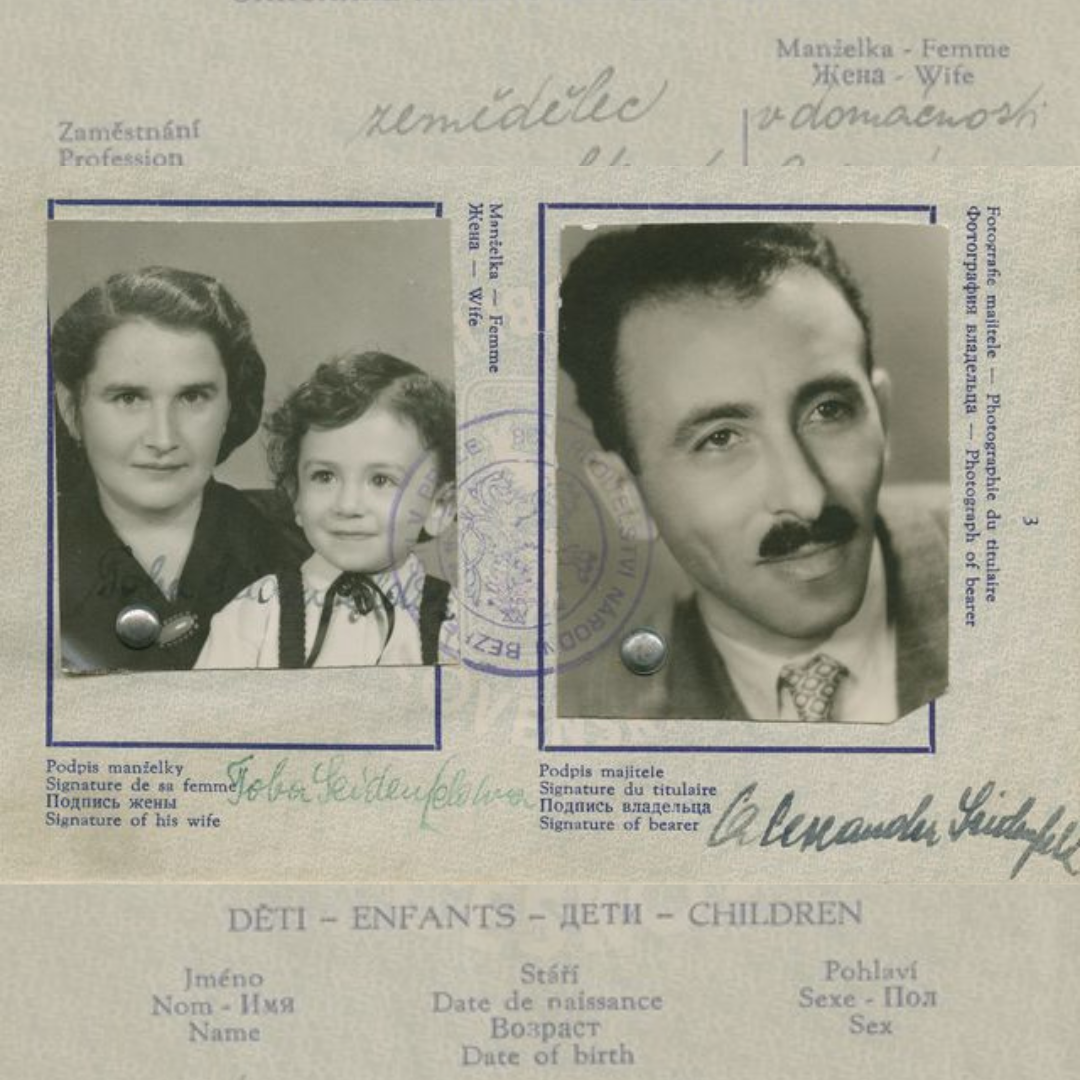

Details of a Czechoslovak passport. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jerome Seidenfeld.

Details of a Czechoslovak passport. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jerome Seidenfeld.

Published by: Academia/Masarykův ústav a Archiv AV ČR

Details of a Czechoslovak passport. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jerome Seidenfeld.

Details of a Czechoslovak passport. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jerome Seidenfeld. In 1945, an Auschwitz survivor returned to her ransacked home in liberated Subcarpathian Ruthenia, where she luckily found a certificate, confirming that before the war her sister had attended a Czech school in the province. This document, together with affidavits from teachers who had taught her before the Second World War, allowed the said survivor to apply for the permit to opt for Czechoslovak citizenship and move to Prague. Otherwise, she could have faced a real threat of being forcedly repatriated to the Soviet Union. This story, which is only one piece in the mosaic of the predicament experienced by Jewish survivors after 1945, demonstrates the uncertainties faced by Jews in post-war Czechoslovakia, the subject of Magdalena Sedlická’s recently published monograph.

Historians have long argued that the liberation of the concentration camps did not immediately bring an end to the Jews’ predicament. Survivors experienced difficulties when trying to reintegrate into post-war societies, and in some territories encountered outright hostility from their neighbours, who rarely welcomed them back with open arms, hoping to keep the spoils of the war. Cases of anti-Jewish violence occurred regularly, especially in the territories with a weak central government or strong local anti-Communist resistance, for example in Poland.1

Sedlická shifts our attention to Czechoslovakia, which before the war had often been considered or rather presented as a model liberal democratic entity in the sea of authoritarian regimes. Jews enjoyed full citizenship rights and could even register Jewish nationality in the official census, regardless of the language they spoke. Yet as Sedlická demonstrates, also in Czechoslovakia Jewish survivors faced immense difficulties with reintegration, especially when they tried to confirm their Czechoslovak citizenship, the main prerequisite for their physical and material restitution in the country. Disappointment and sadness are the most common sentiments expressed by survivors in their memoirs and recorded testimonies. The monograph focuses on the initial post-war period of 1945-48, and the “possibilities and limits of reintegration” of the Jews. In contrast with neighbouring Poland, the Jews in Czechoslovakia, especially in the western provinces of Bohemia and Moravia did not experience any threat of physical violence from the local population. There were no violent pogroms, or cases of random violence that would take survivors’ lives. This, however, did not mean that they did not experience significant complications in their efforts to reintegrate.

The monograph is divided into five main chapters, starting with a brief introduction to the origins of the Czechoslovak post-war policies, before the author gradually moves on to discuss the experiences of selected groups of survivors. The final chapter then offers insights into the situation in Slovakia, which although differing in terms of the severity of local antisemitism and prejudices, at the same time offers some interesting points of comparison with the Czech provinces.

None of these groups […] fit into post-war Czechoslovakia, reimagined as an ethnically homogenous state of Czechs and Slovaks.

Although most of the Jewish survivors in the Czech provinces experienced at least some difficulties after their return to the country, Sedlická centres the main part of her analysis on three groups: the Jews, who were identified with German culture; Jews who declared that they belonged to the Jewish nation; and Jews who before the war had lived in Subcarpathian Ruthenia – the easternmost province ceded to the Soviet Union in 1945 – but after the war wanted to opt for Czechoslovakia. None of these groups – either linguistically, culturally, ethnically, or with their religious beliefs – fit into post-war Czechoslovakia, reimagined as an ethnically homogenous state of Czechs and Slovaks. In her research Sedlická builds on the works previously published by other authors (Kateřina Čapková, Michal Frankl, Jan Láníček), but hers is the first systematic attempt to offer a global coverage of the diverse Jewish groups in Bohemia and Moravia that experienced persecution in a comparative perspective with the neighbouring states. Furthermore, she worked with sources that so far have not been fully explored by historians of the Jewish experience in Czechoslovakia, in particular with the extensive troves of recorded testimonies held in the Jewish Museum in Prague and other repositories. The ways in which ordinary survivors experienced the first post-war years allows Sedlická to offer a nuanced argument, which takes into consideration the direct and indirect impact of state policies on individuals’ lives.

Sedlická offers three main conclusions. First, the new authorities in post-war Czechoslovakia clearly declared their intention to remould the ethnic composition of the country. This redefinition and unification of society was fundamental, at least in the authorities’ opinion, for the internal and external strengthening of the republic. The German minority, numbering almost 3 million before the war, was transferred from the country to Germany, and there was also an unsuccessful effort to exchange ethnic Hungarians who lived in Slovakia for Slovaks settled in Hungary. Furthermore, as Sedlická confirms the conclusions of other historians, Jews, who perceived their identity in ethnic terms, were expected to move to Palestine.2

Those who wished to stay had to undergo full assimilation into the Czech or Slovak nation. All the Jews who did not or who were not identified by the state or majority societies as belonging to the Czech and Slovak communities faced immense difficulties when trying to get a confirmation of their national reliability and their citizenship.

the decision about the fate of the Jewish survivors was based on the decisions they, or their parents, took more than 15 years before

Crucially, the decision about the fate of the Jewish survivors was based on the decisions they, or their parents, took more than 15 years before, in the early 1930s during the last pre-war official census, or based on the schools they had attended, and cultural institutions and associations they had patronised. The fact that these decisions were made under completely different circumstances even before Hitler came to power in Germany, and began to threaten Czechoslovakia, did not seem to bother the new authorities. Not only were their citizenship rights in danger, but the Jews identified as non-Czech could be forcedly resettled either in Germany – as other “Germans” – or sent to the Soviet Union in the case of those from Ruthenia. Only interventions from the Jewish community at home and abroad in the end managed to stop most of the deportations, but some of the survivors most likely had to leave their homeland only a few months after their return from Auschwitz.

This leads us to the second main conclusion, where Sedlická argues that these decisions about individuals’ fates were in the hands of local officials who often received vague instructions or intentionally applied stricter interpretations of the laws. Decisions made by the Jews in 1930 based on their social contacts (membership in associations and clubs, or quality of education), as a matter of practical convenience (proximity of educational institutions to home), or simply without any deeper consideration, were after 1945 retrospectively taken as serious political declarations that shaped the fate of survivors. Whilst individuals could not change their past behaviour and decisions, the state could clearly change its assessment of their past actions. Behaviour that was seen as in line with the democratic practice of interwar Czechoslovakia, was now seen as a manifestation of disloyalty to the state and its population.

All these negotiations and other efforts of the survivors to reintegrate were then – and this is the last main conclusion of the monograph – impeded by anti-Jewish sentiments within society. Although the Jews in the Czech provinces did not experience any fear for their lives, they often encountered latent antisemitism, and disappointment that “so many” Jews were coming back.

The way she skilfully analyses the decision making of the Czechoslovak state, the behaviour of local officials who had the power to decide the fate of the individuals, as well as the reactions of ordinary Jews who had to undergo the whole ordeal, are the main strengths of Sedlická’s excellent monograph.

Jan Láníček is Associate Professor in Modern European and Jewish History at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. He is currently completing a study of post-Holocaust judicial retribution in Czechoslovakia and also researches Jewish migration to Australia before World War 2. Most recently we was the co-editor with Jan Lambertz of More than Parcels: Wartime Aid for Jews in Nazi-Era Camps and Ghettos (Wayne State University Press, 2022).

Není přítel jako přítel: Židé v národním státě Čechů a Slováků, 1945–1948 [Unequal Friends: Jews in the National State of Czechs and Slovaks, 1945-1948]

Published by: Academia/Masarykův ústav a Archiv AV ČR

1 Gross, Jan T. Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz: An Essay in Historical Interpretation. New York: Random House, 2006; Engel, David. “Patterns of anti-Jewish violence in Poland, 1944–1946.” Yad Vashem Studies 26, no. 1998 (1998): 43-86; and Cichopek-Gajraj, Anna. Beyond Violence: Jewish Survivors in Poland and Slovakia, 1944–48. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

2 Láníček, Jan. Czechs, Slovaks and the Jews, 1938-48: Beyond Idealisation and Condemnation. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.