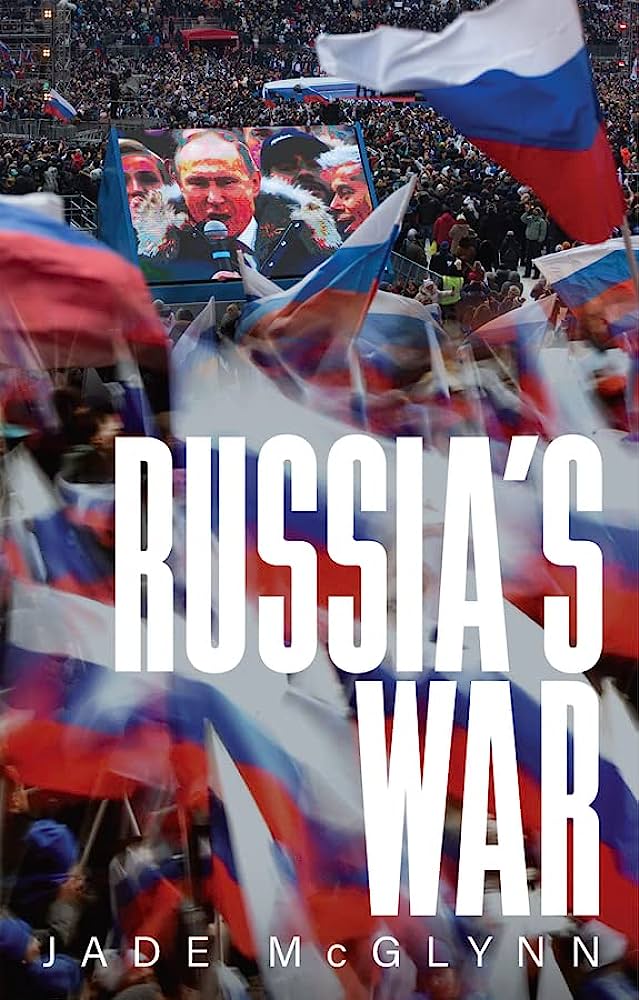

Russia’s war and public support for the invasion of Ukraine

Published by: Polity

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 unleashed a barrage of death and destruction, the likes of which Europe had hoped it had consigned to the past. Amidst the shells, missiles, aerial strikes, and gunfire another war was being fought, an information war characterized by propaganda, disinformation, myth making, and the use and abuse of history. This was a disorienting and bewildering moment for many scholars of Ukraine, Russia, and eastern Europe, although nothing compared to what Ukrainians were forced to experience. A torrent of comment, analysis, and speculation followed as experts attempted to make sense of rapidly changing events. Heated debates and discussions ensued in the press, broadcast media, public lectures, conference panels, on blogs, and social media. The complexities and implications of this conflict, however, are not easily reduced to sound bites, tweets, or op-eds. A year on from the start of Russia’s offensive scholars are turning to more carefully constructed arguments and book length studies. In Russia’s War Jade McGlynn makes a valuable and impassioned contribution to the rapidly growing corpus of books about Russia’s invasion. This readable and carefully researched study dispels many of the myths, falsehoods, and inexpert claims which have swirled around this conflict.

“Putin doesn’t shape Russian views on foreign policy or Ukraine so much as he articulates them”

The central premise of Russia’s War, as the title highlights, is that this is more than Putin’s War. An undertaking as complicated as the so-called, “Special Military Operation,” cannot be imposed from above in response to one man’s obsessions, even if many western leaders and policy makers understandably frame the conflict as Putin’s sole responsibility. The book examines, “Putin as the symptom not the cause,” (p. 4) and explores the historical myths, resentments and traumas that have been channeled by the state to prepare Russia for war. McGlynn’s, “purpose in writing this book is to explain why Russians support the war and what that support actually means in a context (almost) devoid of political agency” (p. 3). Far from passive recipients of Kremlin policy and propaganda, she argues that Russian society is complicit in generating the forces that led to the escalation of the conflict and its murderous conduct. The narratives that justify the war are co-creations which resonate with ordinary Russians. As McGlynn notes, “Putin doesn’t shape Russian views on foreign policy or Ukraine so much as he articulates them” (p. 9). Russia’s War acknowledges the range of attitudes and positions amongst Russians, the complexities of evaluating popular opinion in Putin’s Russia, and the challenge of neatly categorizing people’s responses. Nevertheless, it argues that “Russia’s war on Ukraine is popular with large numbers of Russians and acceptable to an even larger number” (p. 5). In advancing these arguments, the book avoids essentializing Russians, and guards against so-called “whataboutism” by acknowledging the complicity of British and American populations in recent wars and other forms of western hypocrisy. As the book’s conclusion notes the West has frequently failed to acknowledge how it has facilitated this war, “not by NATO expansion but by allowing Russian elites to steal at home and spend abroad” (pp. 213-4).

The book’s eight chapters are divided into two main sections, the first four dealing with Putin’s personal popularity and the ways in which Kremlin propaganda operate; the last four focusing on how and why certain pro-war narratives appeal. Chapter two concentrates on the problem of assessing public opinion in a highly authoritarian regime, and gauging support and opposition to war. Far from denting Putin’s popular appeal, his ratings increased after February 2022, alongside expressions of patriotic sentiment. Chapter three reminds the reader of the different discourses that surround the war in Russia, Ukraine, and the West. Euphemistic language like the “special military operation” and the effective ban on using the word “war” demobilizes opposition and feeds the large number of shifting narratives which frame the conflict for Russians. This chapter unpacks and contextualizes many of these propaganda narratives, including notions that: Russia is fighting a pre-emptive defensive operation; that Russia is fighting to save Ukraine from nationalists and fascists who usurped power via a coup in 2014; and that the morally corrupt West is determined to destroy Russia. Here McGlynn brilliantly demonstrates how Russian propaganda works, not necessarily by persuading people, but by confusing them and overwhelming their critical faculties. “By unleashing so many confusing and confused narratives at once, you bamboozle people” (p. 50). This creates apathy and encourages people to retreat to fixed concepts and familiar cognitive patterns. Nevertheless, Russians have been at the center of intensive agitational effort, especially on television and social media. In the wake of the invasion entertainment programs disappeared from screens, replaced by an increasingly emotional foreign affairs coverage. This coverage and the narratives that emerged online, especially on Telegram channels, play on anti-Ukrainian tropes cultivated since 2014, inducing heightened emotional responses rather than convincing people of the truth of facts or official interpretations.

Russia’s War offers important insights into, “why Russians acquiesce in, and deny the reality of, their genocidal war on Ukraine”

The second half of the book deals with more controversial aspects of Russia’s framing of the war in greater detail. Chapter five explores how and why many Russians understand the invasion as a war with the collective West, fought for a new global order. It explains Russia’s fears and anxieties about NATO expansion, the prominence in Russian analysis of the Yugoslav wars and Kosovo, and how accusations of western Russophobia, as well as claims that Russia is protecting traditional values, have been weaponized. McGlynn concludes that, “any discussion that centers on NATO expansion as a key driver for Russia’s invasion and/or insecurity is simplistic” (p. 118). These arguments, as the next chapter demonstrates, strip Ukrainians of agency, reducing Ukraine to a sphere of influence or buffer zone caught between Russia and the West. Chapter six explains the vilification and hatred expressed towards Ukrainians in Russian public discourse, and how and why Russia, “underestimated Ukrainian society’s courage, resilience, and competence” (p. 137). The chapter reveals much about why Russia, and much of the West, misunderstood contemporary Ukraine. The remaining chapters demonstrate how so much of Russia’s actions are underpinned by history, a theme that runs throughout the book. History, particularly the memory of the Second World War, has been instrumentalized. Furthermore, many of Russia’s anxieties are underpinned by failures to come to terms with aspects of its history, especially the long shadow of past traumas.

Russia’s War offers important insights into, “why Russians acquiesce in, and deny the reality of, their genocidal war on Ukraine” (p. 205), at a time when accessing Russian ideas and attitudes presents great methodological challenges. McGlynn draws on a wide range of media sources, public opinion materials, and nearly sixty interviews with influential and well-connected respondents. Aimed at a wide audience, Russia’s War is written in a lively and accessible style, which sweeps the reader through its arguments at pace. Although informed by approaches from social and media theory, the prose avoids jargon and technicalities, concentrating instead on explaining complicated issues with precision. Anybody wishing to better understand why Russians continue to support this murderous conflict will learn much from this pithy and insightful study. Occasionally the non-specialist might have benefitted from a fraction more context, for example the significance of politicians like Boris Nemstov or Anatoly Chubais (p. 100) or TV programs like the satirical show kukly(p. 52) might have been fleshed out. This, however, does not detract from this astute dismantling of Kremlin propaganda narratives, and careful unpicking of the frustrations, grievances, and resentments that underpin Russian, “aggressive form of patriotism, denigratory attitudes towards Ukrainians, (and) inferiority complex towards the West” (p. 208). Although, Russia’s War is a gripping read its message is chastening. This war is unlikely to end with a change of President; it will require deep-seated attitudinal change amongst ordinary Russians. As McGlynn concludes: “The Russian vision of the past must change in order for Russian society to recognize the realities of the present.” (p. 216) Such a prospect looks a long way off.

Robert Dale is Senior Lecturer in Russian History in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at Newcastle University, where he has been based since 2015. His research interests centre upon how Soviet society dealt with the aftermath of extreme and traumatic events. He has published widely on the aftermath of the Second World War in the Soviet Union after 1945, focusing particularly on the complicated processes of post-war reconstruction and recovery. His book Demobilized Veterans in Late Stalinist Leningrad: Soldiers to Civilians was published by Bloomsbury academic in 2015. He has recently published articles on aspects of Russian and Soviet war memory in Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History and the Journal of War and Culture Studies.