Socialist Silicon Valley

Published by: MIT Press

Discussions of science and technology in socialist Eastern Europe have long centered on the Soviet Union, its immense scientific-technological sector, isolated science cities, advances in various theoretical fields and military-adjacent technologies, its initial lead in the space race and cybernetics. In the hierarchy of scientific-technological capabilities of countries comprising the Eastern bloc, East Germany would typically be seen in a distant second place, with other countries, which were assigned specific niches according to the principles of the international socialist division of labor, further down the list.

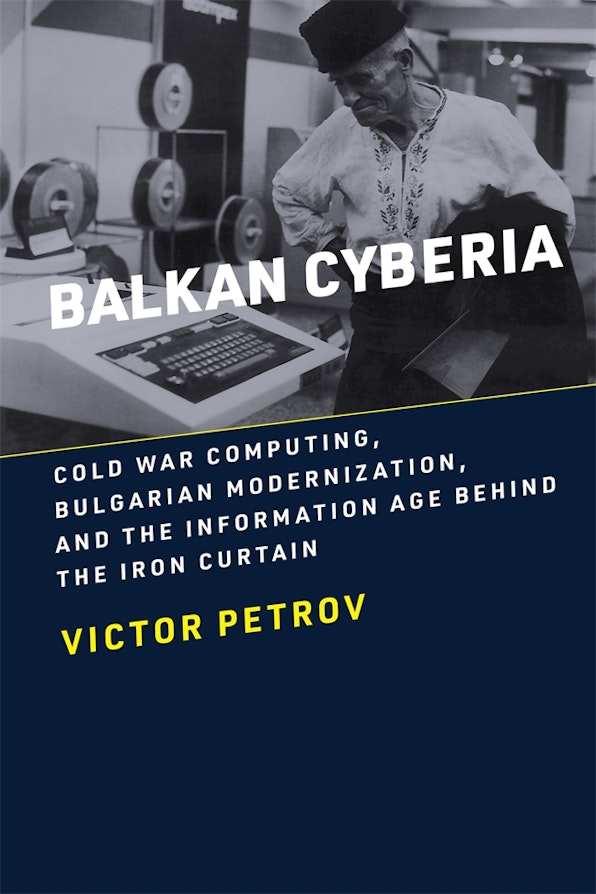

Viktor Petrov’s Balkan Cyberia: Cold War Computing, Bulgarian Modernization, and the Information Age Behind the Iron Curtain offers a different perspective. Petrov convincingly—occasionally even amusingly—tells the story of a small socialist country which in the 1960s made a high-risk strategic bet on the emerging electronics industrial-technological sector. By the 1970s it had become the leading producer of electronics in the Eastern bloc, eventually accounting for 45 percent of the electronics trade in the Eastern bloc, as well as one of the larger manufacturers and exporters globally (third in per capita production of electronic hardware).

Drawing on official documents, memories, oral history, and popular magazines, the book examines the geopolitical and socio-economic contexts in which the rise of Bulgaria’s electronics industry happened, the reasons for its struggles toward the end of the socialist period and during the transition to liberal capitalism, the knowledge networks and circulation of people, knowledge, and artefacts needed to manufacture specific technological artefacts, from hard drives to supercomputers, as well as the wider cultural implications of a computerized socialist modernity. “The Bulgarian computer is a prism,” Petrov argues, “through which one can tell a story of the late twentieth century’s multiple trajectories of technological change, socio-economic shifts, and socialism’s modernity” (p. 5).

This is the reasons why spies and industrial intelligence work are so prominently featured, with Petrov describing the efforts to acquire specialist knowledge and advanced technology from the other side of the Iron Curtain

The book opens with the exploration of economic and industrial-technological discussions that led to Bulgaria’s entry into the field of electronics, and introduces the towering figure of Ivan Popov, a scientist-manager primarily responsible for making it a success story. The core of Petrov’s argument, explaining how and why Bulgaria’s bet—unlike similar bets made by other countries, including, prominently, East Germany—actually paid off, is that Bulgaria managed to renegotiate its role within the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), cooperated as well as competed with other members of the bloc, and recognized and addressed the technological needs of the dominant force, the Soviet Union. The result was Bulgaria’s “capture” of the Comecon market. (The supposed statement by Bulgaria’s leader, Todor Zhivkov, that “Bulgaria is [doing] well, because it has colonies and the biggest one is the USSR,” (p 105), nicely summarizes this.) As a latecomer—Albania and Bulgaria were the only socialist countries which had not domestically manufactured a digital computer by 1960—the country needed access to advanced technology to outmaneuver its socialist competitors.

Collaboration with Japanese companies, which started in the 1960s, proved to be critical in this regard; it also allowed Bulgaria’s fledging electronics industry to mitigate the limitations on technology transfers to the Eastern bloc imposed by the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Exports Control. This is the reasons why spies and industrial intelligence work are so prominently featured, with Petrov describing the efforts to acquire specialist knowledge and advanced technology from the other side of the Iron Curtain—but also to share information with, and spy on, other socialist countries. Bulgaria also cooperated with India and a number of developing countries in the Middle East and Africa. While much of recent scholarship on the East–South cooperation during the Cold War has emphasized ideologically driven solidarity, Petrov depicts Bulgaria’s “electronic entanglement with India” in more pragmatic terms, arguing that, as a result, “a whole new generation of younger cadres learned the rules of marketing, negotiation, and business more generally” (p. 175).

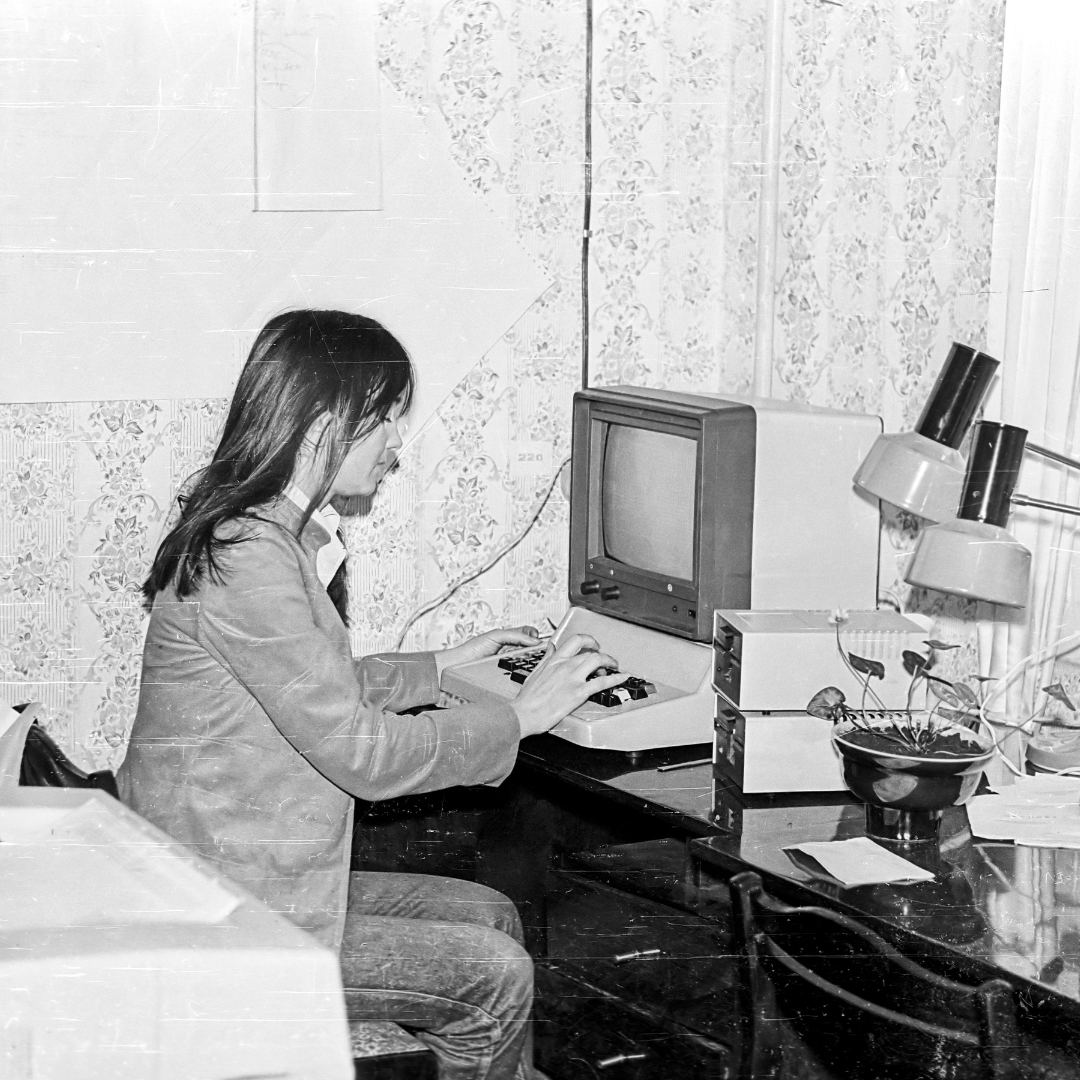

The fixation on scientific-technological revolution was typical of late socialism. If the Bulgarian case was in some way special, it is probably because the “stuff” of the third industrial revolution was much less of an abstraction, and Petrov offers insight into the day-to-day workings of a (partly) computerized socialism, including those that provoked workers’ resistance. From stores and factory floors, the book takes us to the sphere of education, culture, and ideology in discussing the “socialist cyborg” and the futurists’ visions. Petrov finally offers a sort of prosopography of “computer priests,” a community which comprised party officials, proto-entrepreneurs, and notorious hackers such as the Dark Avenger alike, reaching across the 1989 divide. There is an interesting dichotomy between the industry (the larger socio-economic system) and individual people at work here: “Socialism’s factories failed—but the people remained” (p. 314), even if they no longer lived and worked in Bulgaria. The perseverance of “cadres”—at least those whose careers were not cut short by the deindustrialization of the 1990s—seems to be the most enduring legacy of Bulgaria’s big technological bet.

Petrov offers a distinctly revisionist account, yet the book’s main finding seems almost expected in light of recent historiographical trends such as de-centering the history of the “Soviet Empire” and heightened interests in global connections, especially those involving the Global South. Not many people, of course, would have guessed that it was Bulgaria that played such an outsized role in the global electronics industry, but it would not have been unreasonable to expect to learn that a small socialist country had carved an industrial-technological niche for itself, developed global, trans-systemic lines of collaboration, and profited from it. Much to his credit, Petrov has convincingly shown this was the case with Bulgaria.

Bulgaria made a giant leap into computerized socialist modernity between the 1960s and 1980s, hundreds of thousands of workers found employment in the electronics industry and the export revenues boosted the country’s finances.

I struggle a bit with assessing the overall tone and the “moral” of this great book. It is essentially a history of techno-optimism, but its tone in places also seems to be techno-optimist. Petrov takes us deep into the world of Bulgaria’s technology specialists—occasionally so deep that the Bulgaria outside of their laboratories, meeting rooms, and discussions can get obscured. He makes it abundantly clear that Bulgaria’s was a qualified success, that technological deserts surrounded high-tech islands, that investments needed for maintaining competitiveness, especially on the global markets, were becoming prohibitively expensive by the 1980s and that Bulgaria’s fortunes were fundamentally tied to its “captive market,” which collapsed after 1989. Bulgaria made a giant leap into computerized socialist modernity between the 1960s and 1980s, hundreds of thousands of workers found employment in the electronics industry and the export revenues boosted the country’s finances. Yet I was left wondering about the overall impact of Bulgaria’s bet on electronics, especially one that would refer back to the economic-political debates about peripherality from the 1950s and 1960s, as discussed in chapter 1.

Because of that, the book lends itself to different readings, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. It can be read in a nostalgic key, remorseful of lost knowledge, skills and, most important, lost futures; as an inspiring story of the periphery challenging the hegemony, both of global capitalism and of the Soviet Union; in a techno-optimist as well as a techno-pessimist key, showing the limits of the transformative power of technology; as a study of a bet on high technology-driven development which, unlike in so many comparable cases, paid off, but primarily (or only?) because of uniquely well-timed policy interventions. It therefore speaks of the contingent and fragile nature of success stories such as the Bulgarian leap into computerized socialist modernity. Whatever the reader’s preference, Balkan Cyberia will prompt both specialists and the wider audience to discuss the history of science and technology in socialist Eastern Europe in new ways.

Vedran Duančić specializes in modern intellectual history and history of science, with a particular interest in the intersection of science and politics. He is a senior scientist at the Department of Knowledge, Society and Politics at the University of Klagenfurt. He is the author of Geography and Nationalist Visions of Interwar Yugoslavia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), and is currently working on topics in the history of science, medicine, and technology in socialist Yugoslavia.