Socialist Yugoslavia’s migrant workers in the capitalist West

Published by: University of Toronto Press

In the decades after the Second World War, nearly one million men, women, and children from socialist Yugoslavia joined the steady flow of migrants seeking work in western Europe. The Yugoslav migrants, like others making the journey from southern Europe, North Africa, South Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and other corners of the globe, set out for Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Austria, and France, where they took advantage of special visas and work programs designed to recruit laborers to participate in the rebuilding of western Europe after the devastating war. They found work in factories, construction, infrastructure, and service industries. Some came for short stints. Some stayed for decades.

While their journeys and lives abroad shared many similarities to those of other migrant communities, the Yugoslavs’ journey was unique: they not only crossed political boundaries, but ideological ones as well. They came from the “other” side of Europe, the socialist side. They were raised in a country where ideas of labor, politics, rights, and economic structures were grounded in Marxist principles, and where capitalism and the west were demonized. And they retained connections to the socialist world, even as they made their lives and livelihoods in western Europe. Unlike the dissidents, exiles, and émigrés who permanently left the Soviet Union and various Communist countries, including Yugoslavia, these worker migrants kept Yugoslav citizenship, property, and deep family, cultural, and linguistic ties to their country. They used their hard-earned Deutschmarks and francs to build new two- or three-story vacation and retirement homes back home, a mark of wealth and prestige. They traveled home for vacation, inherited family property, got married to other Yugoslavs, and maintained friendships. Indeed, they moved back and forth between the capitalist and socialist worlds, understanding each side in relation to the other. Their bodies, their money, and their ideas cut through the artificial Cold War boundaries of East and West.

What did it mean for a socialist state to relinquish control over the political and economic worlds of its citizens abroad? How did Tito’s authoritarian regime and the Yugoslav Communist Party try to maintain connections, influence, and control over its citizens living in capitalist societies? How did migrants respond to being educated in the values of both the socialist and capitalist worlds, and to the possibility of moving between them? Where was home?

If the socialist workers’ state was meeting the needs of its people, as it claimed to do, why were so many workers leaving for the capitalist west?

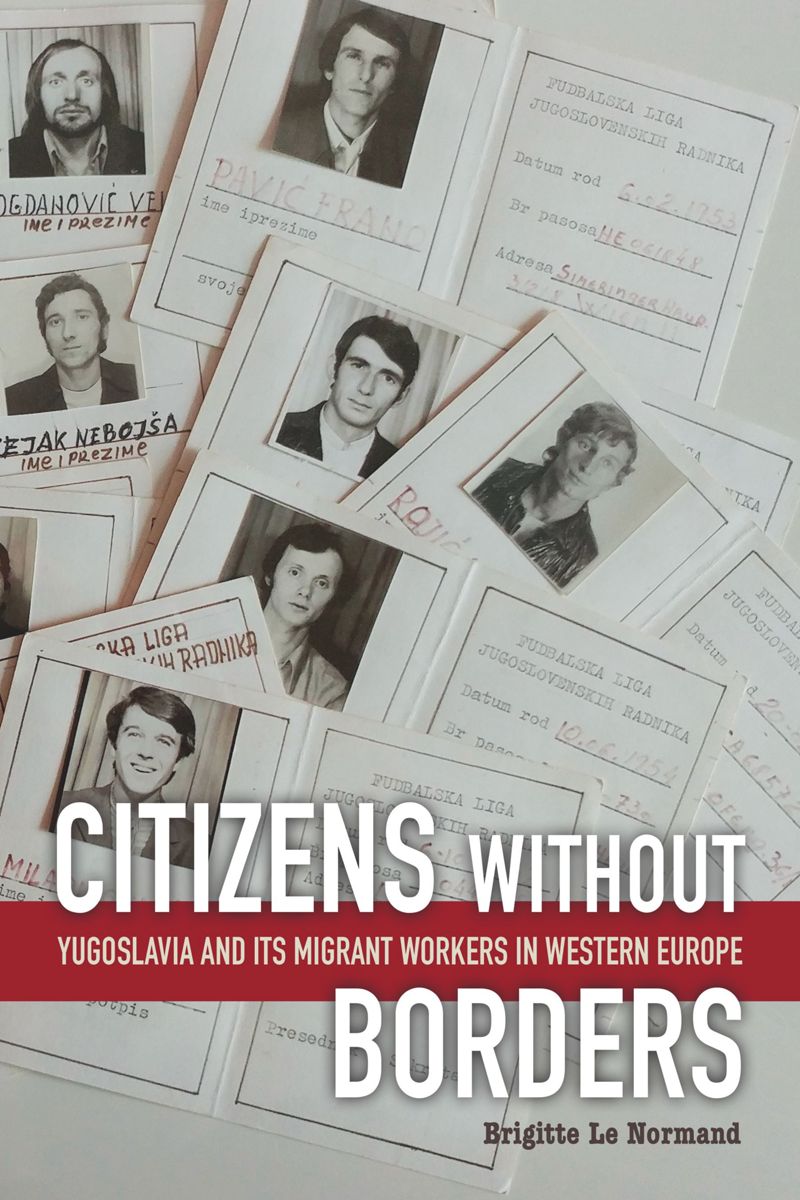

These questions undergird Yugoslav historian Brigitte Le Normand’s new study, Citizens without Borders: Yugoslavia and Its Migrant Workers in Western Europe. Drawing upon archival, art, film, radio, and newspaper sources, Le Normand examines the relationship between the socialist state and its citizens living in western Europe. Centering migrant experiences and Yugoslav state initiatives, the book is about Yugoslavs and Yugoslavia. Le Normand analyzes how conceptual and legal-cultural categories such as citizen and expatriate, migrant and workers abroad, emerge as part of a complex dialogue among the country of origin, the place of migration, and individual experiences moving between and within these different places. In so doing, she complicates notions of sovereignty by uncovering how foreign states worked behind the scenes to entice, indoctrinate, and inspire loyalty of their citizens abroad, and she probes disparate ideas of homeland that are fostered within diasporic communities.

Socialist Yugoslavia had a complicated relationship with its migrants in western Europe. Until the 1960s, state authorities perceived them as largely non-threatening. But gradually, they realized that these citizens posed both an image problem and a political one. If the socialist workers’ state was meeting the needs of its people, as it claimed to do, why were so many workers leaving for the capitalist west? State authorities grew concerned about bad press and the negative influences of people immersed in capitalism who had free access to their country. Their anxieties deepened in time of political and economic crisis, when they worried that migrants might be growing distant, disillusioned, or nationalist. State officials feared that some migrants could be influenced or targeted by diasporic political activists and anti-Communist dissidents who plotted terrorist attacks and hoped to overthrow the regime. Indeed, as Le Normand notes, such groups occasionally targeted the migrant workers, including a deadly attack at a Tiefbau plant in Germany that left ten dead. The remaining migrants got the message: they packed their bags and moved back to Yugoslavia.

Yugoslav cultural producers tackled the image problem at home through film. Popular films critiqued both the migrants and the west, discouraging new men and women from joining them abroad. Yugoslav films also sought to counter myths of the west by portraying the difficulties of everyday migrant life and the violence they faced at the hands of west European authorities. Such efforts sought to challenge western propaganda that depicted western states as less repressive or rigid than those in Eastern Europe.

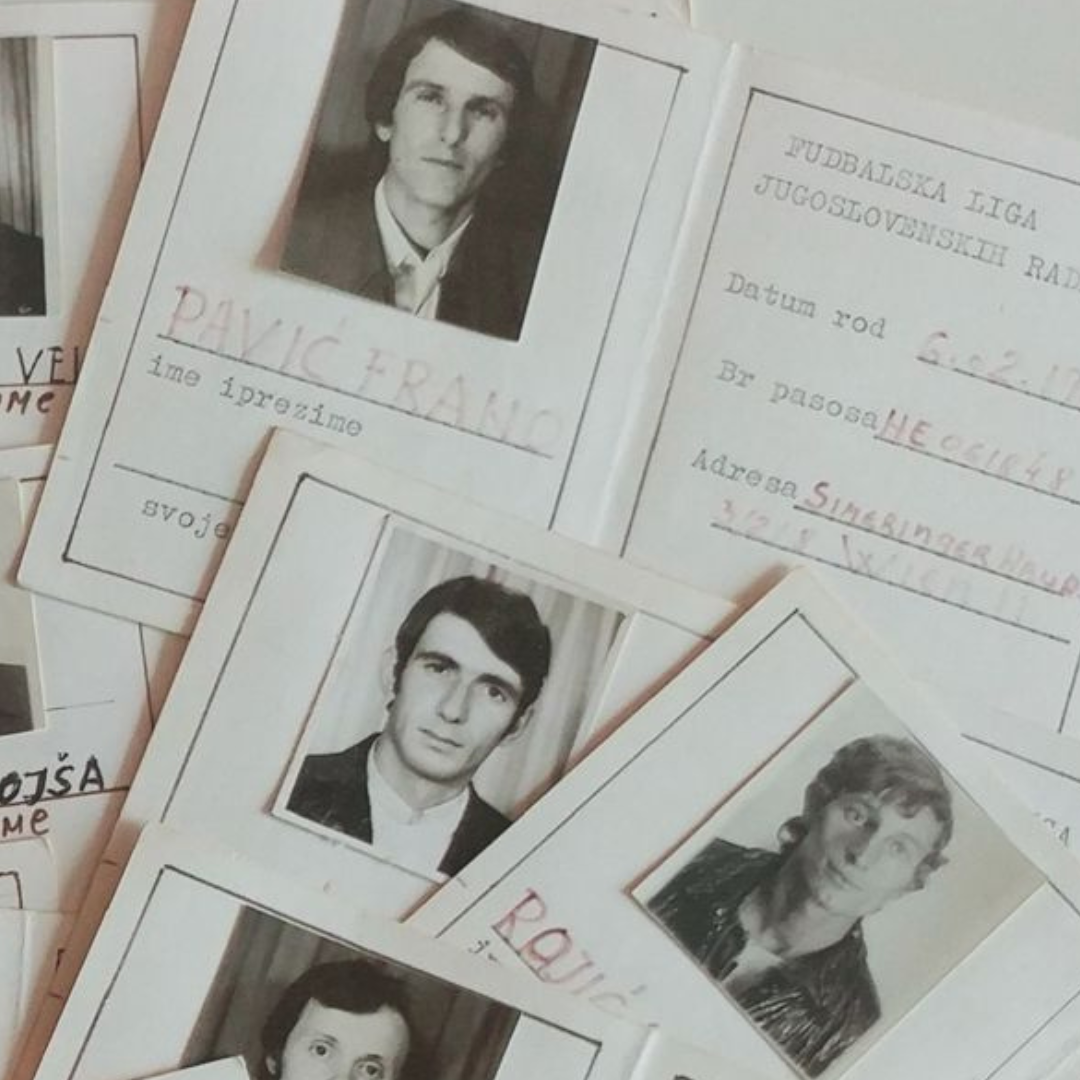

Most of the state and Communist Party’s attention, however, focused on the migrants themselves. If these citizens would be living and working abroad and crossing between the two states and the two worlds, the socialist government needed to know them, to understand what made them tick, to win and retain their loyalty to Yugoslavia, and to maintain influence over them. Their tactics were wide-ranging. They established radio stations and citizen associations that aimed to strengthen loyalty, cement socialist values, and foster feelings of a diasporic Yugoslav community. They launched an elaborate survey campaign to gauge migrant workers’ thoughts about life abroad and life at home. They sent teachers abroad to educate Yugoslav children on their history, language, and culture, an education steeped in socialist doctrine. Through soft power diplomacy, educational networks, and film and media, they created an image that these migrants were part of a broader Yugoslav whole.

Central to this project was creating an interconnected Yugoslav diaspora. While Croats, Serbs, and Slovenes might think of themselves as distinct émigré communities, a Yugoslav diaspora would transcend these internal national and regional lines and foster the state ideology of “brotherhood and unity” abroad. Le Normand points out that one particularly successful strategy was state-sponsored radio programs. People from different parts of Yugoslavia, now living all over Europe, shared a common listening experience. Through radio programs, the migrants reminisced about their favorite songs, shared tips for navigating nebulous and changing visa requirements, and warned each other about passport scams. They mourned together when crisis hit home, such as during the 1964 flood in Zagreb, and organized collections of food, appliances, household goods, and money. Such programs created links among the diverse Yugoslav migrant workers listening in their kitchens or living rooms across western Europe. Radio programming targeting expatriates thus fostered a feeling of shared homeland.

But Le Normand also shows that this idea of homeland was a tricky one: some diasporic radio programs and newspapers presented alternative visions of homeland and political belonging rooted in distinct Croat, Slovene, and Serb national ideologies. Others encouraged stronger connections with local histories. State and party organs struggled with the messiness and complexity of national and regional particularism within their own associations and programs, which were designed to foster collective identity and patriotism but often became places for people from one or another particular national group to congregate.

In a refreshing twist to European history, west European states play a supporting role in Le Normand’s narrative

In a refreshing twist to European history, west European states play a supporting role in Le Normand’s narrative: for example, we learn of Austria’s hostility to the creation of the Yugoslav pioneers, a socialist youth group, and France and Belgium’s refusal to let Yugoslav teachers work in their public-school systems. Such examples shed light on how west Europeans responded to Yugoslavia’s thinly disguised campaigns of political indoctrination through cultural venues, while centering the socialist state’s campaigns abroad.

Le Normand opens many paths for future study. She complicates our understanding of how the Croatian spring was experienced and shaped by those in diaspora, raising questions about how this distinct political moment might be re-evaluated through diasporic perspectives. She also raises important questions about how émigrés and migrants, as two distinct communities of “Yugoslavs” abroad, interacted and understood one another. Did nationalist émigrés and dissidents also listen to the Yugoslav radio? Did they see the migrants as potential allies or as agents of the socialist state living among them? While hinting at the possible ties between migrant communities and the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Le Normand chooses not to take the speculative leap of connecting her findings to the rise of nationalism and secessionist politics that would contribute to Yugoslavia’s dissolution in the 1990s. However, readers are left wondering how mass media, which she persuasively argues was used to mobilize diasporic communities during the socialist period, might have played similar or different roles in mobilizing migrants as war broke out. We also wonder how these migrants responded to émigré efforts to undermine Yugoslavia and assert Croat and Slovene independence.

The historiography of postwar migration centers west European political and social structures and the experiences of temporary workers and migrants from colonial territories. Le Normand makes an important intervention by examining the experiences of socialist European citizens living and working in a capitalist world and the ways that a socialist state sought to claim them. In teasing out this other dimension, Citizens without Borders challenges us to rethink our presumptions about the ideological, economic, and human boundaries built into our ideas of Cold War Europe.

Emily Greble is Professor of History and East European Studies at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. A historian of the Balkans, she is the author of Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe (Oxford, 2021) and Sarajevo, 1941-1945: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Hitler’s Europe (Cornell, 2011).