The Ambivalent Autonomies of Romania’s Socialist Youth

Published by: Cetatea de Scaun

Contrary to many interpretations, which stem mostly from Foucauldian paradigms, there is more to dealing with the disciplinary mechanisms of state apparatus than simply being reluctantly complicit with or submitting to them altogether. The possibility does exist to ignore or even adjust them to one’s own interests, as does the possibility for resistance and action. A more superficial glance could easily mistake one for the other, however, especially in the case of totalitarian regimes, regardless of the ideology they espouse.

Challenging the common notion of the absolute power of state socialism and going beyond the obvious and already well-documented conflicts between the regime and Romanian youth during Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime, the chapters in Tineri și tineret în România Socialistă aim to focus instead on the so-called “grey areas”. These are the areas where youth came to interact with the Romanian Communist Party’s strategies designed to implement socialist consciousness but also to discipline and ultimately control its bearers. Such grey areas are thus re-mapped as sites where the subjectivity and agency of the Romanian socialist youth were formed through the constant negotiation of and adaptation to the official ideology. The volume addresses topics such as the ways in which Romanian youth used Western arts and cultural experiments in order to articulate their own alternative identity and practice, state control of citizens’ free time, the idea of a national (as well as socialist and anti-imperialist) rebirth made possible through the revitalization and recovery of traditions among young people, the ideological incursions into book production and youth literature, and the regulation of sexual behavior. In doing so, it endeavors to provide a more nuanced narrative by decentering the socialist state/party and its conflict with Romanian society, also spotlighting how young socialist citizens “created meaningful structures and autonomy niches in the ideological space broadly defined by the state party” (p. 12).

youth was identified as a social category that presented the highest risk to the state regime

The early 1970s marked the end of the liberalization of social life, arts, and culture in Romania as Ceaușescu became more interested in controlling the freedom of Romanian society. Against this increasingly restrictive socio-political background, youth was identified as a social category that presented the highest risk to the state regime in terms of rejecting the conformity promoted and demanded by it. Since “the body and its future children were the property of the state” (p. 21), this particular age group was also considered to be part of the process of building the new socialist man. In her chapter that documents the period when almost 6,000 Greek children were evacuated and resettled in state institutions (children’s homes/colonies) in Romania during the Greek Civil War (1946-1949), Beatrice Scutaru focuses on the politicized dynamic of these spaces-cum-laboratories that functioned according to rules inspired by the Soviet model. Productivity and participation in the future construction of the nation and country were core ideas that were taught (albeit not always successfully) in these colonies. In her conclusion, Scutaru is also careful to emphasize that the presence of the state, be it in the form of humanitarian aid and institutional care or in the form of its own political propaganda, was a common denominator in these children’s lives.

The state’s regulation of sexuality, culminating in pro-natalist policies and the criminalization of abortion, also included pro-family propaganda as Luciana M. Jinga notes in her chapter on gender, pronatalism, and sex education. Marriage was an institution instrumentalized for the (re)instatement of youth-directed control, with the insistence on the nuclear family seen as the only way towards “real” socialist monogamy as opposed to capitalist monogamy, which was perceived as something exclusively guided by economic interests. Children played an important part as they could strengthen the family, but they were also championed as the supreme joy for heterosexual couples, as in “communist Romania there were no homosexuals, only lured, deceived, or abused ones.” (p. 155) Considering the eugenic convictions of endocrinologist Ștefan Milcu, the main proponent of official sex education for youth, Jinga advances the rationale that, besides being intended to prevent the birth of children with health/genetic issues, his own personal agenda was to nationalize sex through excessive medicalization.

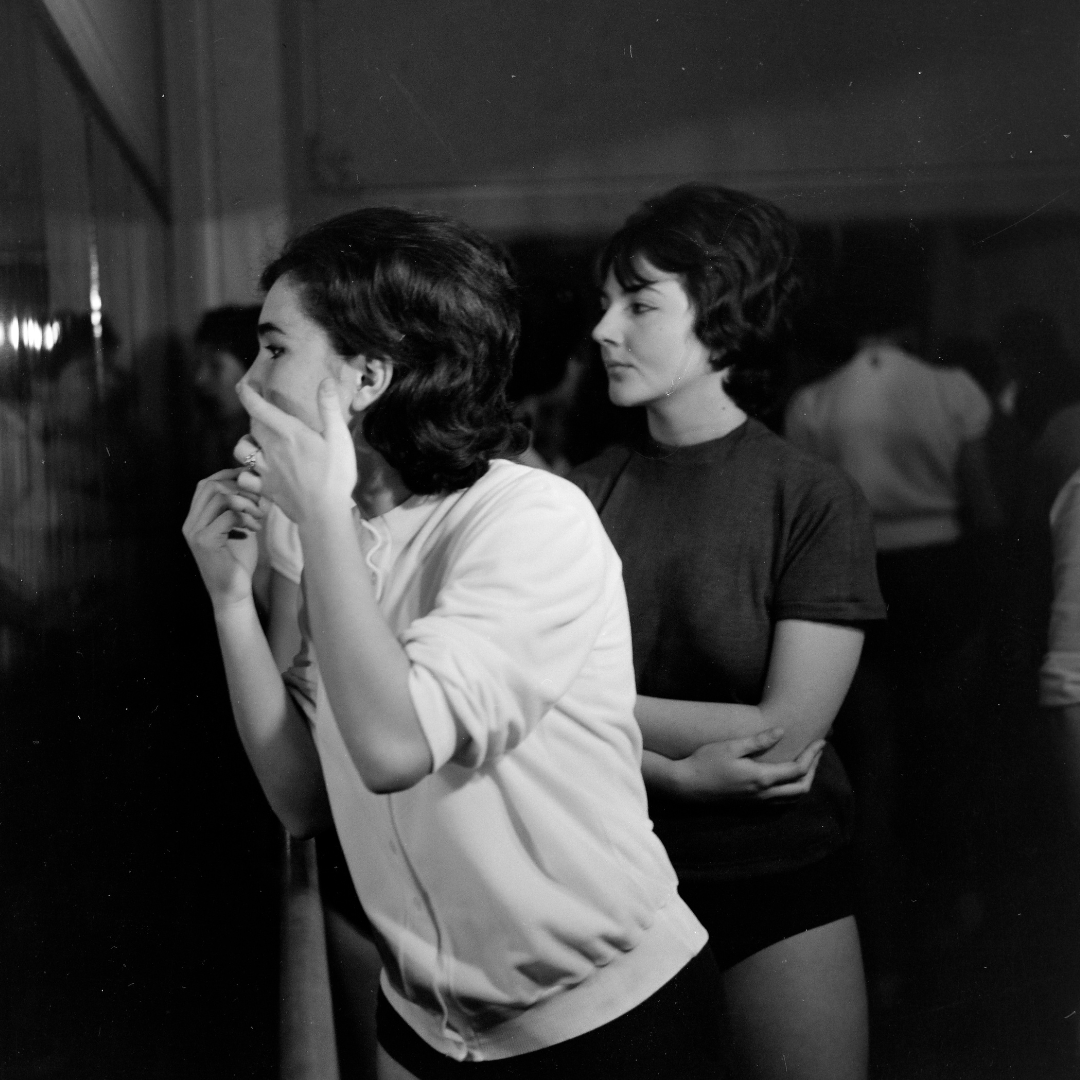

As the archives reveal, many university activities performed by students were not directly linked to the specialization they were studying for. Higher education was thus another youth-oriented area under the direct control of the Communist Party, which it used to promote its own political directives and increase party membership. However, these archives also reveal another important matter: the official discourse and its wooden language could not fully influence, or control student’s lives even if national decision-makers built a whole system to (re)program them as future industrial workers. For instance, the frequency of class attendance among female students, their punctuality, and their dress “left a lot to be desired” (p. 69) while they also showed “deficiencies in the manifestation of a ‘mobilizing spirit within the collective.’”(p. 69) Since youth were the first in line when it came to training for disciplined, compulsory work, their higher education was regarded as a genuine act of social pedagogy.

Free time was […] a precious commodity in state-socialist Romania and youth’s leisure time was no exception.

In an essay entitled “Pork It Is, Then” – Confessions of an Underground Vegetarian, written for the literary website Words Without Borders, the translator Florin Bican recalls his experience with the Securitate (the secret police) who were startled by the mere idea of him spending his free time differently from what they had in mind for him (that is, queuing for meat). Free time was indeed a precious commodity in state-socialist Romania and youth’s leisure time was no exception. This is most obvious in the way cultural activities were designed to both reinforce nationalism and educate young people against Western cosmopolitanism regarded as a major source of “moral pollution” (p. 227). But the counteractivities devised to prevent corruption among youngsters and popularized as “alternatives” were also influenced by the very youth movements abroad (starting in 1968) that the regime was trying so hard to counteract. The best example of this being “Cenaclul Flacăra”, as Andrada Fătu-Tutoveanu’s chapter details, a musical and literary cenacle that “created the environment for youth to resonate with official propaganda, presented in an attractive soft power form” (p. 123). But what underpinned the regime’s endeavors to control how youth were spending their free time and what they were consuming, be it music, art, or books, was the idea that a young person, as a newly built socialist man, was both a recipient and a creator of national culture. However, as Mioara Anton argues in her chapter, exploring alternative culture and the ideological indoctrination of youth, “[i]t is difficult to tell if the attraction for Western cultural productions was a form of revolt/resistance to the regime, or an attempt to find alternative ways to secure the goods and information they wanted.” (p. 212)

In trying to showcase how not everything should be read as youth opposition or resistance to a totalitarian regime set to sanction and regiment every aspect of their private and public lives, the authors featured in this volume challenge many common narratives that are quick to deliver clean-cut categories. They choose a pricklier fruit: to reveal the ambivalence, even duplicity that characterized the relationship between Romanian youth and the socialist state apparatus. One of the starkest examples of this was the power struggles between the younger and older generations of artists, a conflict that was, more often than not, interpreted by some as an act of resistance. But this intentional troubling of waters should not be read as an indictment pointing to a total lack of histories of local resistance. Instead, it should qualify as yet further proof that things between the modern nation/colonial state and its citizens are much more complicated than what binary approaches allow for.

M. Buna is a freelance writer.