The foreign exchange brokers of Cold War Czechoslovakia and USA

Published by: Harvard University Press

In the popular narrative of the Cold War, the Iron Curtain was a nearly impenetrable barrier which separated the unfree East from the free world. Yet as Brian K. Goodman in his new monograph The Nonconformists shows, the Iron Curtain had not been as impassable as one might think, nor was it only possible to pass it in one direction only. Focusing on how literature and politics between American and Czech writers intertwined, Goodman lays out the surprising extent and frequency in which the writers from the two countries influenced each other. As a result, the transnational scope of the work as well as the aim to refocus our discussion of the cultural Cold War toward the Eastern Bloc makes The Nonconformists a valuable addition to both Czech and American literary scholarship.

In the first chapter, Goodman establishes Franz Kafka as the first contact with Czechoslovak writing for Westerners and also as a mysterious writer-ancestor for Czechoslovaks, who due to the Nazi occupation and subsequent communist coup d’état was barely known among the Czechoslovak readership. The second chapter details F. O. Matthiessen’s teaching at Charles University shortly before the communist coup and the impact his left-wing reading of American literature had on his students, several of whom played a notable role in shaping Czechoslovak literature and literary criticism. The focus of the following chapter is the author and editor Josef Škvorecký, who emulated the writing style of American modernists and put a lot of effort into getting them published. The fourth chapter covers Allen Ginsberg’s visit to Czechoslovakia and his fateful expulsion from the country, but also mentions the careful choices of paratexts employed by translators such as Igor Hájek and Jan Zábrana to get Ginsberg and other authors of the Beat Generation published in the first place. Philip Roth’s visits to Czechoslovakia and his campaign for publishing dissident Czechoslovak writers is discussed in the fifth chapter. Finally, the so-called “Gray Zone”, the blurry area between official state literature and dissident writers, is discussed in the example of the Czech Jazz Section, but the chapter also details American literary activism in response to the persecution of Jazz Section members.

it is simple to forget that many Czech writers and dissidents strived for the “third way”, for a multipolar world where differences coexisted, and not a world in which the East strived to be finally reunited with the West as the only inevitable outcome

One crucial aspect of Goodman’s work is the emphasis it places on the Eastern Bloc and the agency of its peoples. The Eastern bloc seems to be all but forgotten by most, which leads to the tendency to narrate the Cold War from the position of the West only. As Goodman further explains, “[a]ll these tendencies have reinforced an outdated narrative of Cold War cultural history that is at once US-centric and unilateral, a picture that includes well-known US literary figures like Arthur Miller but not Václav Havel—and certainly not both American and Czech writing people together in one frame” (p. 19). Consequently, it is simple to forget that many Czech writers and dissidents strived for the “third way”, for a multipolar world where differences coexisted, and not a world in which the East strived to be finally reunited with the West as the only inevitable outcome.

This is also the reason why the chapters on Josef Škvorecký and Roth are the highlights of the book; they cover in detail how these “foreign exchange brokers”, as Goodman puts it, fostered not only literary exchange between the two countries, but ultimately also effected change. Škvorecký’s chapter covers in detail the writer’s numerous activities and strategies he employed to promote American literature in Czechoslovakia, such as creating new contexts through his literary criticism which then were later used to view his own writing. This chapter should be a required reading for many an Americanist, as Škvorecký played an immense role in shaping the literary culture of his country both as a writer and editor, but also as a publisher in exile thanks to his publishing house, 68 Publishers. The chapter on Roth delves in detail into the discussion on the nature of writers and dissent Roth had with several Czechoslovak authors, most importantly Milan Kundera and Ivan Klíma. Goodman makes two very astute observations. First, that the contact between the East and the West in the late 1970s, facilitated through Roth’s activities such as his book series “Writers from the Other Europe”, helped establish “new forms of literary dissent into circulation at a transitional moment in Cold War geopolitics” (p. 182). Secondly, he notes that paratextual matters such as advertisements or blurbs on the covers were important not only for Czech translations of American works, most importantly the Beats, but also for Czechoslovak authors published abroad. In the Czechoslovak context, a careful and clever choice of paratexts allowed the translators and editors to get an otherwise objectionable work past the censors and publish it. In the United States, Eastern European writers were – despite Roth’s efforts – often seen first and foremost as dissident writers who were banned from publishing their work in their home country. In other words, we cannot avoid notcontextualizing a literary work and adapting it to a specific purpose or narrative, and it is valuable to see how exactly this repackaging is brought about.

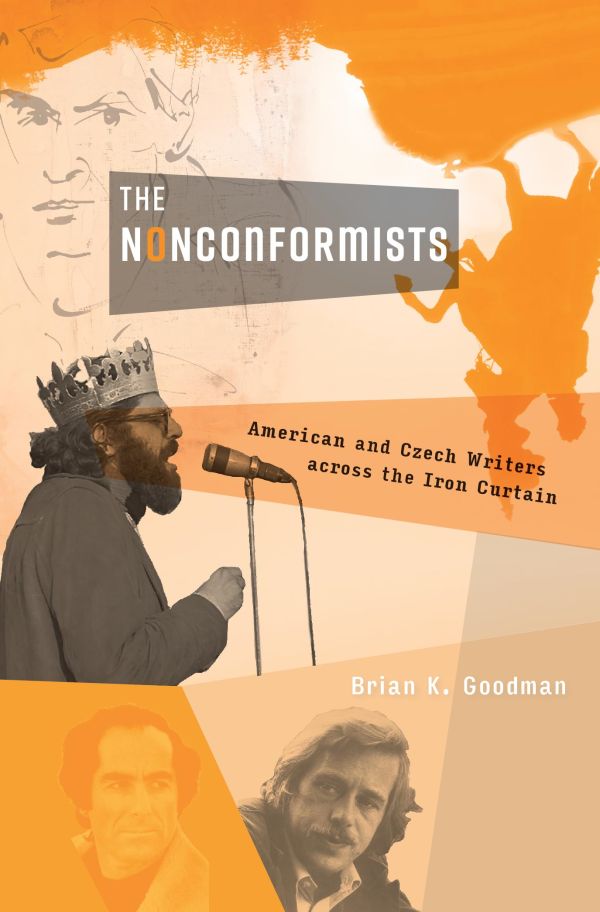

The book is written in a clear, easy-to-read style, which makes it also a good recommendation for readers outside of academia. Goodman’s writing is also generally well-structured, though at times, for example in the chapter on the Jazz Section, he tends to start discussing one area and then return to it only after several pages later in a rather roundabout way. While this organization does make sense in hindsight, it is still somewhat unexpected. Secondly, while Václav Havel is featured rather prominently on the cover, his writing and activism is discussed only briefly in the introduction and the epilogue. I would have preferred a separate chapter on Havel and his idea of the “third way”, though this would most likely warrant a stand-alone book rather than a single chapter. That being said, if Brian K. Goodman were to write such a study, I would definitely put it on my reading list.

Antonín Zita holds a doctoral degree in literature and is currently an assistant professor at the Masaryk University Language Centre, where he teaches classes on academic writing and other academic skills important for writing a thesis or a research paper. His primary research interest is the literature of the Beat Generation as seen through the lens of comparative literature and reader-response criticism. His most recent work is titled How We Understand the Beats: The Reception of the Beat Generation in the United States and the Czech Lands, released in winter 2020.