The Jewish Civic Court and postwar retribution in Poland

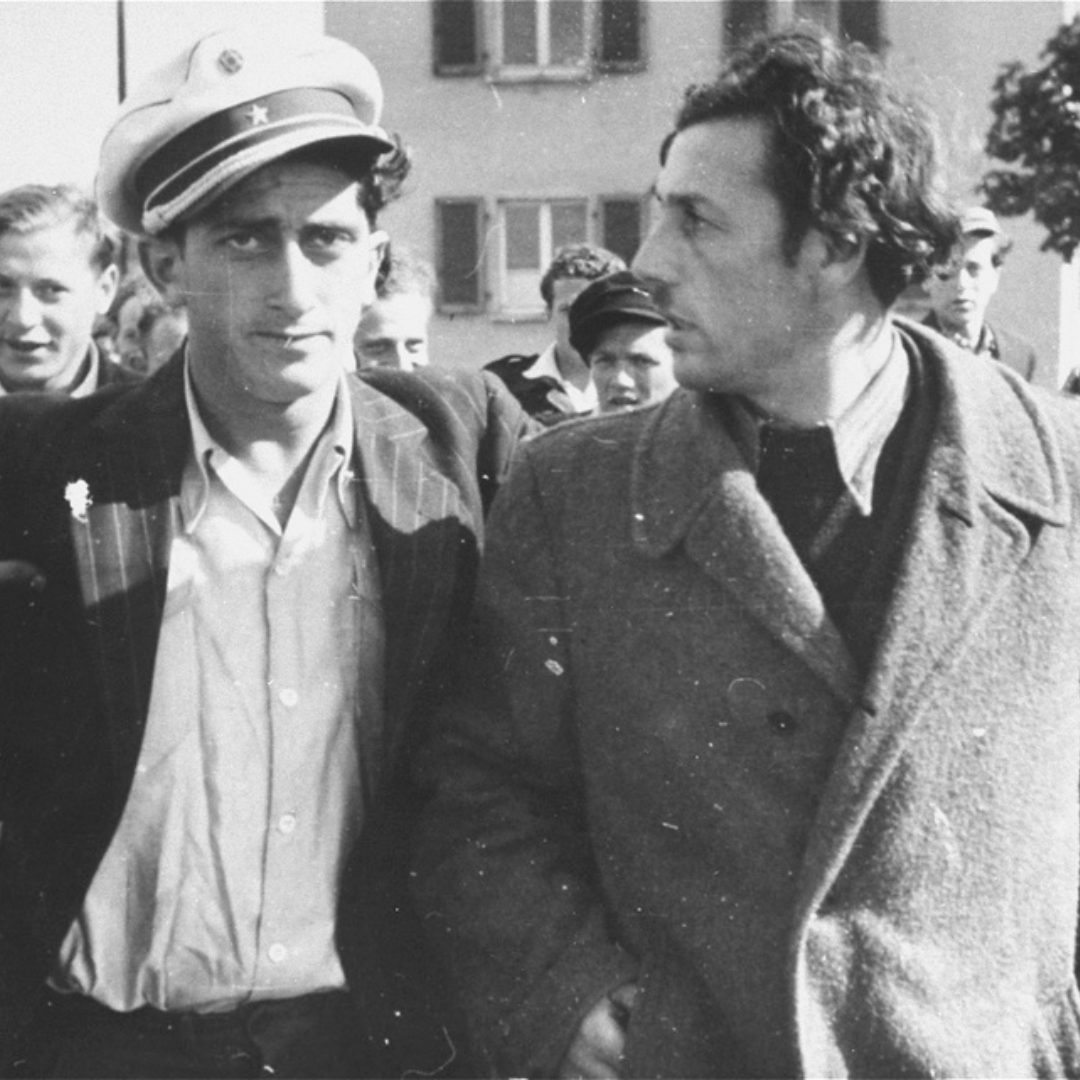

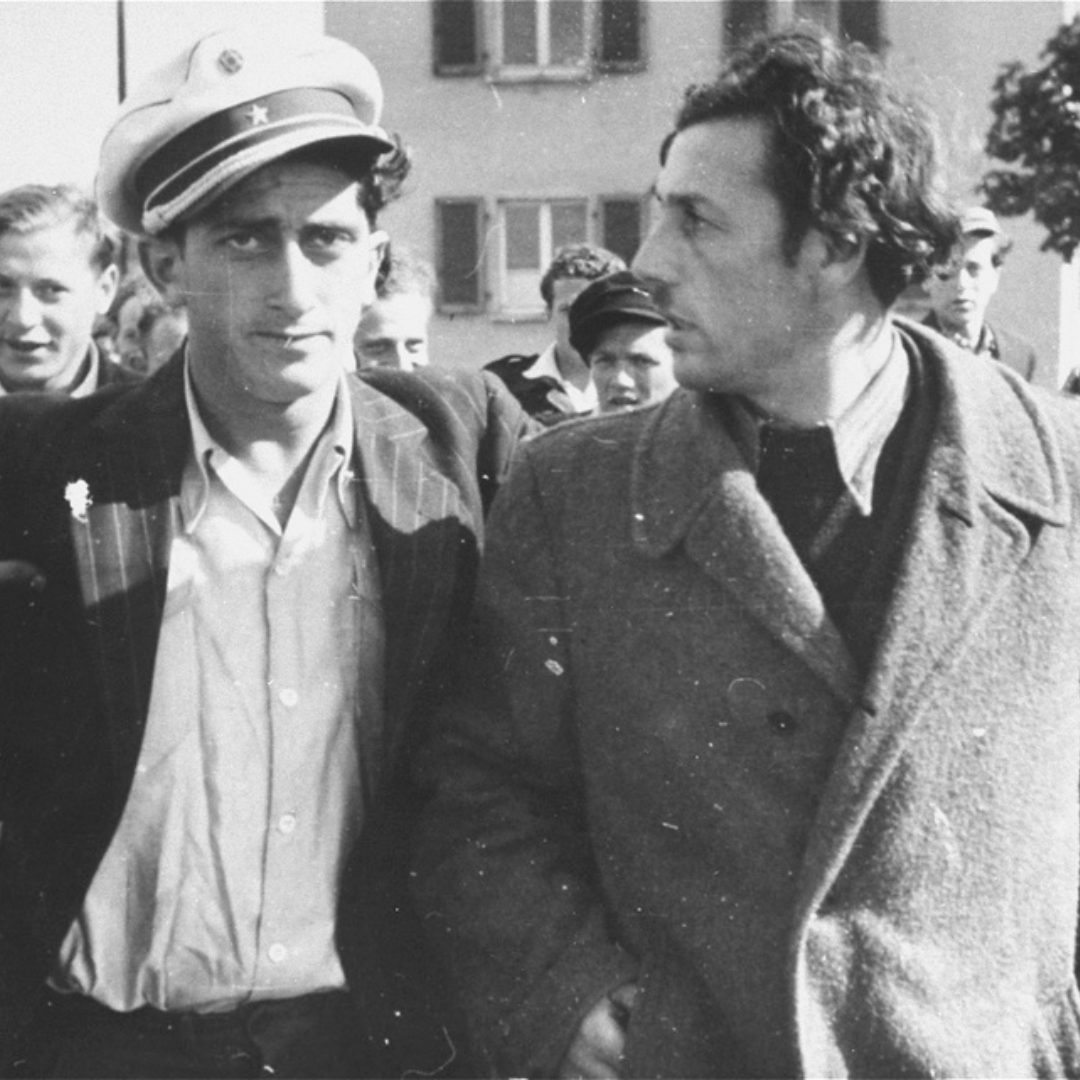

Jewish police detain a former Kapo. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Alice Lev.

Jewish police detain a former Kapo. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Alice Lev.

Published by: Wydawnictwo Czarne

Jewish police detain a former Kapo. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Alice Lev.

Jewish police detain a former Kapo. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Alice Lev. The Jewish Civic Court (known in Polish mainly as sąd obywatelski or sąd społeczny, in Yiddish as folks-gerikht) was operated from October 1946 to early 1950 by the Central Committee of Jews in Poland (Centralny Komitet Żydów w Polsce) – the central postwar representative body of the Polish Jewry. Its mission, in its own words, was to:

cleanse Jewish society of people who in one way or another cooperated with the Nazi authorities during the occupation, unmasking those traitors of the Jewish people who have tens and hundreds of thousands of victims on their conscience. Those traitors consider themselves or want to be considered as decent people and want to try to play a role in the life of our society.

Quote from Gabriel N. Finder, “Proces Szepsla Rotholca a polityka kary w następstwie Zagłady” Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały issue 2 (2006), p. 225.

The court investigated about 150 cases of those suspected of what was then perceived by the Polish Jewish Community to be wartime “collaboration”, with Jews acting against their own community by holding positions of authority in camps and ghettos, participating in various capacities in deportation to death camps, looting or otherwise profiting from the misery of others or working as informers for the German occupiers. In practice, the Civic Court mainly tried members of the Jewish Order Service (Jewish police), who formed over 50 percent of the cases, members of the Jewish Council (Judenrat), informers and prisoner functionaries in concentration and forced labor camps. Among them were 11 women.

A key element of the postwar search for revenge and retribution was its trans-territorial (and often cross-border) character and its reliance on cross-border networks of information.

Men and women found guilty were punished with a rebuke, a reprimand, ostracism, suspension of the rights of a Jewish community member, and exclusion from the Jewish community. The setting up of these courts was a response to the societal failure to recognize the Jewish dimension of the Second World War. The Jewish community had its own memory of atrocity, that it had to deal with on its own. When handing over a suspected collaborator to the Jewish Civic Court, a member of the Jewish community could be certain that the judging panel understood the choices made in the Holocaust, which may have been imperceptible to the outsiders.

In his book, Jakub Szymczak looks at the issue of postwar retribution (and sometimes revenge) among Holocaust survivors, discussing in depth chosen cases from the files of the Civic Courts, which he supplements with files from the Polish State Courts, private documents and a truly impressive investigation into the later fate of those who stood in front of the courts and of their families. He adds new layers of interpretation to cases that are already very well known, such as that of the head of the Jewish Self Help, Michał Weichrt, the famous boxer and Warsaw ghetto policeman Szapsle Rotholc, and the singer Wiera Gran, but particularly fascinating are those cases which take place outside the borders of Poland. A key element of the postwar search for revenge and retribution was its trans-territorial (and often cross-border) character and its reliance on cross-border networks of information. Szymczak’s characters cross borders to escape the suspicion of collaboration, but almost always find this to have been in vain. One such case described by Szymczak took place in La Paz in Bolivia. A female survivor, Runa Fakler, was publicly confronted (hence, de facto a public trial) for profiting from the suffering of others during the Holocaust as the wife of a kapo, or prisoner functionary, in the Płaszów concentration camp (she herself did not hold a prominent position). Fakler was ostracized by her community and beaten up on the street by a victim of her late husband’s mistreatment. As was the case with Fakler, the issue of blame placed on survivors for the deeds of their family members was especially visible in case of women, who were accused of profiting from the crimes of their husbands or partners and thus held responsible for their actions.

Szymczak’s characters cross borders to escape the suspicion of collaboration, but almost always find this to have been in vain.

There is no doubt that in following Szymczak’s book and seeing the postwar search for retribution as a case of transnational emotional culture, tracing the postwar migration paths of Jews from Poland, we can provide a more nuanced, contextualized picture of the developments within the postwar Jewish community around the world as well as links between its scattered members. Szymczak shows us how fractured the transformation from war to peace is, illuminating our understanding of the opportunities for the moral restitution of individuals and the rehabilitation and reconciliation of the community. He shows not only how complex these cases were, but also, just as importantly, to what extent the shadow of collaboration followed those who stood in front of the court, whether found guilty or not, and remained part of the communal memory of the Holocaust wherever survivors attempted to re-build their lives.

Katarzyna Person is a historian of the Holocaust , the head of the research department in the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Ja łebków nie dawałem. Procesy przed Żydowskim Sądem Społecznym.

Published by: Wydawnictwo Czarne