The memory politics of the Serbian Church

Published by: CEU Press

Karin Roginer Hofmeister’s energetically researched Suffering and Resistance is the latest addition to the growing literature dealing with the Serbian Orthodox Church. Making use of the ideas of Pierre Bourdieu (among others), Hofmeister argues that “memories of trauma create a sense of belonging and solidarity for the abstract community of victims, both national and transnational” (p. 80). And it is precisely the Serbian Church which has long been stirring up traumatic memories, often centering on the Second World War when 307,000 Serbs died in the fascist Croatian puppet state. As Socialist Yugoslavia decayed in the second half of the 1980s (breaking apart in 1991-92), the Serbian Church played a central role in reconstructing and transforming the collective memory of Serbs, as Hofmeister points out. In Serbs’ reconstructed memory, martyrdom and victimhood would lie at the core. And, as psychologists have documented, persons who see themselves as victims feel at liberty to violate the human rights of those they view as their oppressors.

In the Second World War, the Nazis set up puppet states in Croatia (headed by Ustasha leader Ante Pavelić) and Serbia (headed from August 1941 by General Milan Nedić). Both of these Axis states operated concentration camps and both of them collaborated actively with the Axis powers. In addition, parts of what had been the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were annexed variously by Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria, with Kosovo conjoined with Italian-occupied Albania. Two resistance movements quickly emerged: the communist-led Partisans, who fought against the Axis until achieving victory; and the Serb nationalist Chetniks, who operated as an anti-Axis resistance only until October 1941, after which they opportunistically tried to portray themselves as partners with both the Allies and the Axis, until the Allies renounced the Chetniks, leaving them entirely dependent on collaboration with Nedić and the Axis. Here is where the Serbian Church offered a historically revisionist account, for the Church now passed over the Chetniks’ collaboration with the Axis and insisted that the Chetniks were anti-Axis resistance fighters, pure and simple. Trauma, of course, can have a locational focus and here the Serbian Church memorialized Stara Sajmište, site of a concentration camp operated during the Second World War by the Croatian Ustashas, as the centerpiece for Serb traumatic memory.

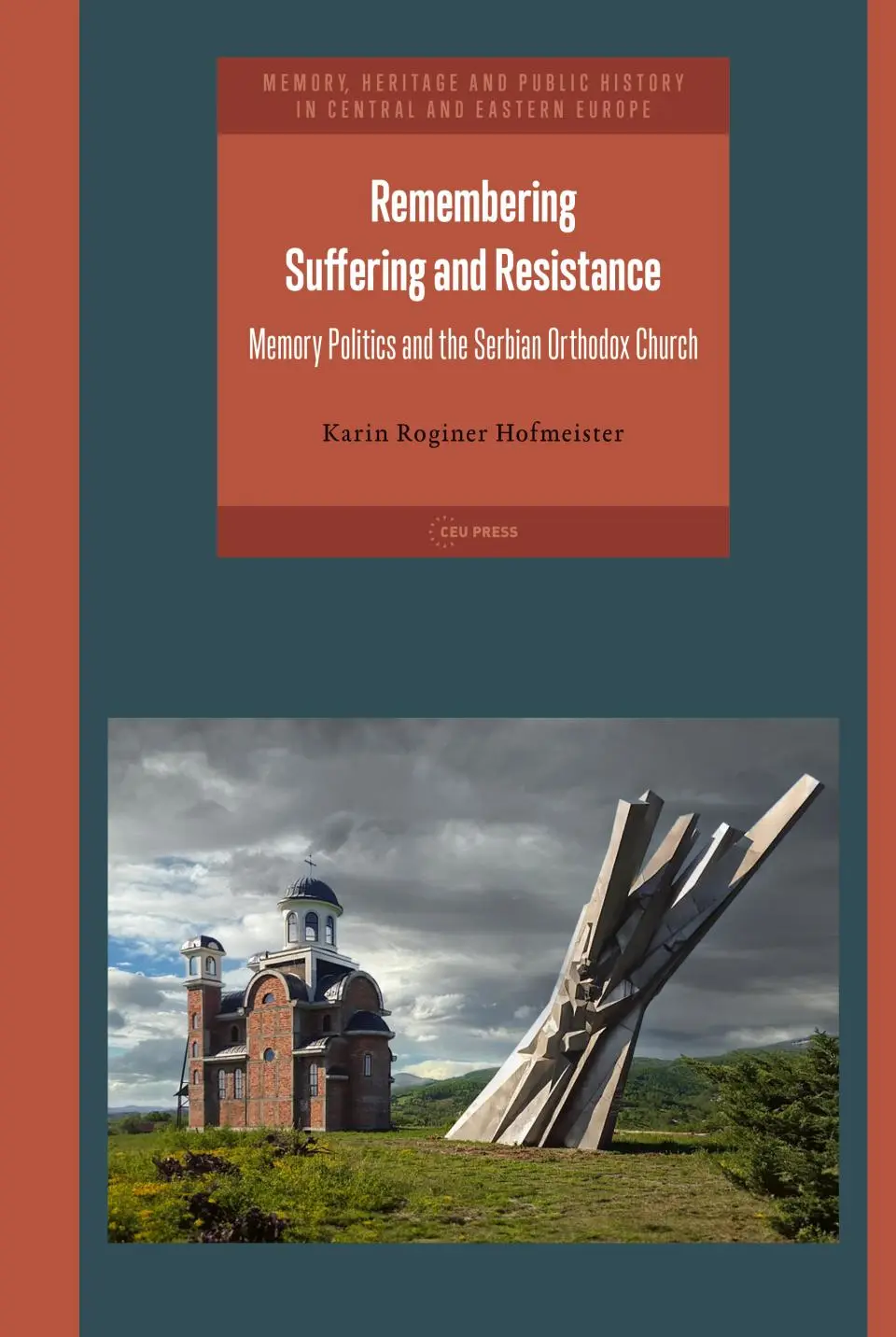

the Serbian Church has occupied itself with setting up shrines or chapels at sites of massacres of Serb civilians during the Second World War, whether in territories that were under Ustasha control or elsewhere, marking such sites with Orthodox Christian symbols.

The Serbian Church benefitted from the Serbian parliament’s passage in April 2006 of a Law on the Churches and Religious Communities. This law renounced the socialist-era formula calling for the Church to stay out of politics (a proscription which, in any event, the Church had repeatedly ignored). Now the Church was able to engage itself in public controversies with the explicit permission of the state, while “working mainly in symphony with the state authorities” (p. 7), as Hofmeister notes. But once Aleksandar Vučić (Serbian Prime Minister, 2014-2017; President since 2017) asserted his primacy in the political sphere, the Serbian Church lost some of its power. Indeed, Serbian Patriarch Irinej acknowledged Vučić’s dominance in 2019, when he awarded President Vučić the Order of St. Sava, the Church’s highest decoration.

Yet, according to Hofmeister, throughout its promotion of an image of Serbs as victims, scapegoats, and in any event misunderstood, the Serbian Church has “proven itself incapable of self-reflection, refusing to critically assess [either] past [or] contemporary problems of the Serbian ethno-national organism” (p. 94). Rather than offering a more nuanced account of the Second World War, in which there were Serbs who were perpetrators of atrocities as well as Serbs who were victims (and, of course, Serbs who were neither perpetrators nor victims), the Serbian Church has occupied itself with setting up shrines or chapels at sites of massacres of Serb civilians during the Second World War, whether in territories that were under Ustasha control or elsewhere, marking such sites with Orthodox Christian symbols. The Church has also restored ecclesiastical facilities destroyed during that war, completing its reconstruction of the church at Jasenovac (in Croatia) in 1984. Again, in order to keep alive the self-image of Serbs as victims, the Serbian Orthodox Church established a Jasenovac Committee in 2003. The Committee rejected as preposterous nationalist claims that at least 700,000 Serbs were killed at Jasenovac (p. 146), yet has been reluctant to acknowledge Serb collaborators with the Axis or the existence of anti-Semitism within the Serbian Church itself even today or in Serbian society more generally (p. 154). Moreover, Hofmeister writes that the Jasenovac Committee has kept silent concerning the collaboration of the regime of Milan Nedić with Nazi Germany and, in 2015, when an initiative was launched to rehabilitate Nedić posthumously, the Jasenovac Committee declined to register an official objection.

What emerges very clearly from Hofmeister’s lucid account is that the Serbian Orthodox Church remains trapped in traumatic memories which it has helped to shape and preserve, in the process limiting its vision for the future.

As for Chetnik leader Dragoljub Mihailović, there has been some support within the Church to canonize him and, in August 2009, Metropolitan Amfilohije (d. 2020) told those assembled in the Cathedral of St. Michael the Archangel in Belgrade that “Dragoljub Mihailović is one of those who sacrificed their lives for their neighbors and their nation and who were sacrificed on the altar of faith and fatherland” (as quoted pp. 193-194). And the Serbian Church has also decorated members of Chetnik organizations, both in Serbia and abroad, with honors such as the Order of St. Sava.

What emerges very clearly from Hofmeister’s lucid account is that the Serbian Orthodox Church remains trapped in traumatic memories which it has helped to shape and preserve, in the process limiting its vision for the future. This is, in sum, a fine book, which anyone interested in Serbian affairs should find of interest.

Sabrina P. Ramet is Professor Emerita of Political Science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), in Trondheim, Norway, and the author of 16 scholarly books, co-author of three, and editor or co-editor of 41 books published to date.