The new woman in Vienna

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

No scholar working on gender in central European history can avoid one ubiquitous figure: the “new woman.” The term is inescapable in this context because it was on everybody’s lips in the interwar period. With so much written about this image in its own time as well as in historiography and criticism, what new insights are to be gained from a new book on the subject? For all the discourse on the new woman, it is startling that precisely who “she” was is so elusive: the term signified everything from women expressing their own agency in life, to independent professionals, to women perceived as masculine, to flapper fashions of boyish haircuts and mannish suits, to sexualized vamps and to women who did not need men for anything at all. All its referents reflected a social anxiety about gender disorder and the challenge to patriarchy, and yet, was there a single thing indicated by such a capacious term? Or was it a cipher without a referent? To paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir, in this maelstrom of contradictory representations, were there any “new women” at all?

In this splendid new treatment, Katya Motyl engages thoroughly with all these discussions, and yet approaches them from a game-changing critical vantage. The “new woman” as a representation, sexist or emancipatory, is not really her concern. Instead, she considers the ways in which the term signifies an embodied practice that entails female activity within the context of modernity. Recent scholarship has turned to women’s active agency in their changing roles in society, as opposed to how they were depicted in caricatures. Motyl’s research and interpretation demand a shift from “new woman” as epithet to a new subjectivity that had an impact on history. She focuses on the conscious and unconscious ways in which women performed challenging roles, how they took control of their “embodiment.”

The city’s intensive transformations over four decades unfold in five chapters, where facets of the new woman figure embody these histories.

The book also intervenes in the broad historiography of modernity studies focusing on cities. The city for Motyl, as for others in urban studies, has an active agency of its own. “New women” altered the complexion of these presumed radically novel spaces, even as they were reflections of them. Turning to women’s experience of themselves in space casts light on what the figure of the new woman was all about. In multiple ways, this book is as much about Vienna as it is about gender. The city’s intensive transformations over four decades unfold in five chapters, where facets of the new woman figure embody these histories. In each of these cases, Motyl exposes how tendencies associated with the interwar period and attributed to the First World War were already present at the turn of the century.

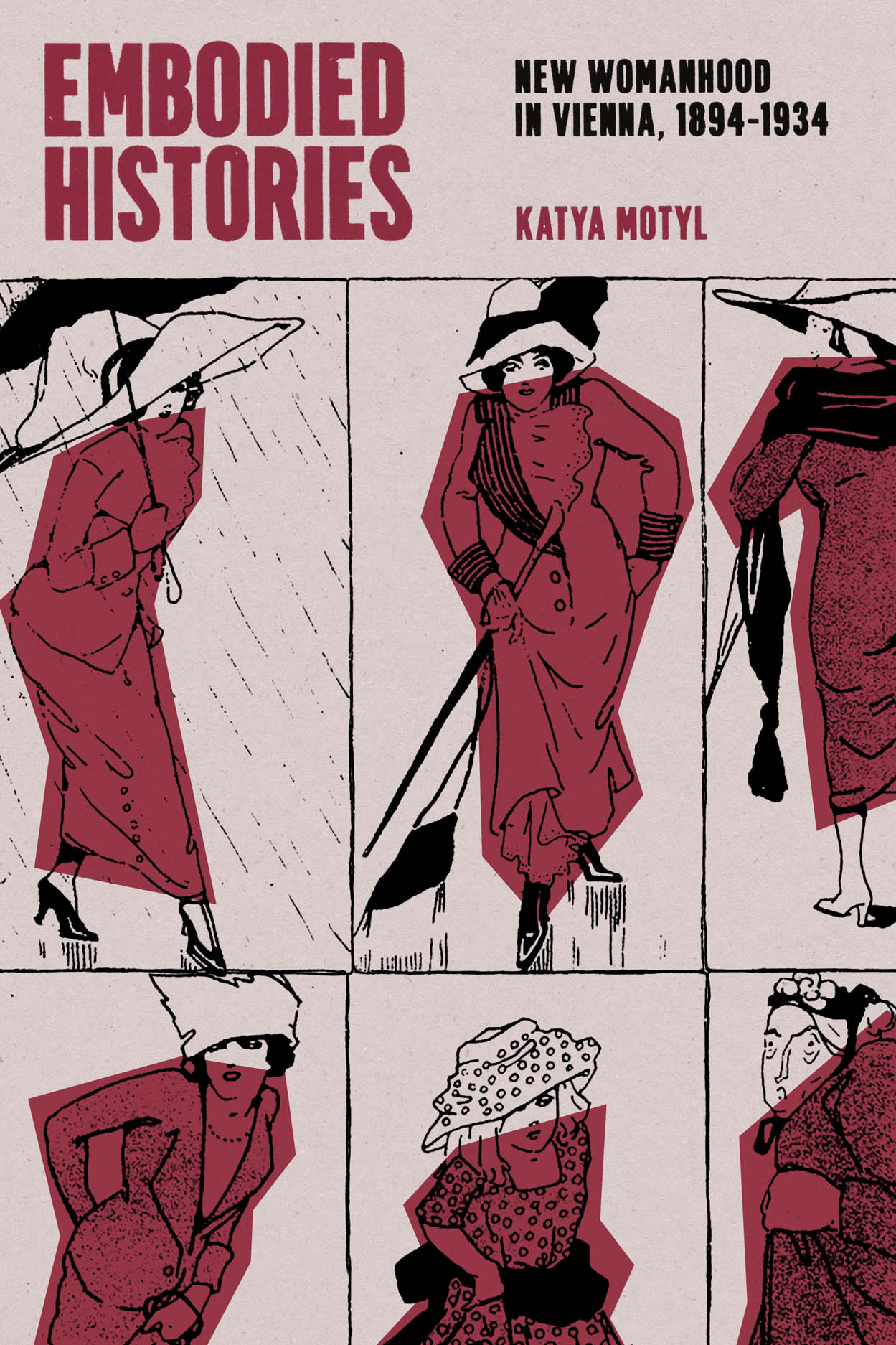

The first of these facets is the evolving urban space of Vienna in the late nineteenth century, engendering a new way of moving through the city as a woman, actively observing it (flânerie), and displaying a defiance of assumptions about women’s sexuality. The new “cultures of walking” represented an actively embodied subjectivity that helped define the structure of the city itself in a reciprocal process, a “trans-corporeality” (p. 68). This power of bodies to change themselves within urban history and thereby impact it continues in chapter two, a study of the changing shape of the interwar female form. A “curvaceous” corporeal ideal yielded to the “linear silhouette,” anticipated by the “masculine line” of prewar fashion and then reflecting a slimness and gender ambiguity proceeding from the hunger years from the mid-war to its aftermath. The history of the body is its own subfield within gender and sexuality studies and has been the subject of discussion among historians since at least the 1990s. Motyl is respectful of this tradition even as she offers analysis that compels it further. Real women’s bodies appear in these chapters within the nexus of women’s lived experience, their representation, and their relationship to the context of the modern city. Instead of Bordieu’s productive concept of “habitus,” Michel de Certeau’s Practice of Everyday Life is for her a more apt theoretical source in its focus on the tactics of embodied practices to resist social forces even as they are subject to them.

Beyond its innovative arguments about the new woman, the book contextualizes the figure within the specific frame of Vienna from the Habsburg Empire to the ideological crisis of 1930s Austria.

In chapter three Motyl turns from the consumer culture of the fashion industry to mass culture, specifically popular theater and cinema. These “expressive” arts mirrored the panorama of public performance of emotion and self-expression that was key to the embodiment of a female subjectivity advocating for itself. The social theory engaged here is Norbert Elias’s, whose assumptions about nineteenth-century emotional restraint are belied by Vienna’s fin-de-siècle women. Motyl’s fine analysis of specific films and theatrical performances brings out women’s roles in these performative expressions of emotion. (Among the very rare sources Motyl seems to have missed, Sara Jackson’s groundbreaking research on “the problem of the actress” in the German-language sphere would be useful here, but parallel insights emerge without it.) Chapter four takes up the theme no study of the new woman can miss, namely that of female sensuality and its self-expressions as well as educational discourses disciplining and in dialogue with it. Chapter five traces the public consciousness of juridico-medical visions of the female body and reproduction, with a particularly engaging excursus on the traces of women’s agentive accounts in abortion trial records. An epilogue looks briefly at the afterlife of the new woman figure(s), including the backlash against it/them, before summarizing the book’s analyses. This summary is admirable for an utterly transparent and direct articulation of arguments and their consequences of the sort that so many authors shy from.

Beyond its innovative arguments about the new woman, the book contextualizes the figure within the specific frame of Vienna from the Habsburg Empire to the ideological crisis of 1930s Austria. This localization is significant for Austrian history and adds new dimensions to the assumptions about the new woman figure so often centered on Berlin. The time frame of the book is a further innovation, beginning at the turn of the century, when most studies have focused on the radical shifts caused by the First World War; she carries the discussion through to the radical reforms of the city under the policies of Red Vienna. The book can be anticipated to have a significant historiographical impact on several fields. For a work with such subtle reasoning and deep theoretical implications, it is a refreshingly lucid read, and an illuminating one.

Scott Spector is the Rudolf Mrázek Collegiate Professor of History and German Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author of Prague Territories: National Conflict and Cultural Innovation in Franz Kafka’s Fin de Siècle (2000); Violent Sensations: Sexuality, Crime, and Utopia in Vienna and Berlin, 1860-1914 (2016), and Modernism without Jews? German-Jewish Subjects and Histories (2017) and has co-edited After the History of Sexuality: German Genealogies with and beyond Foucault (2012).