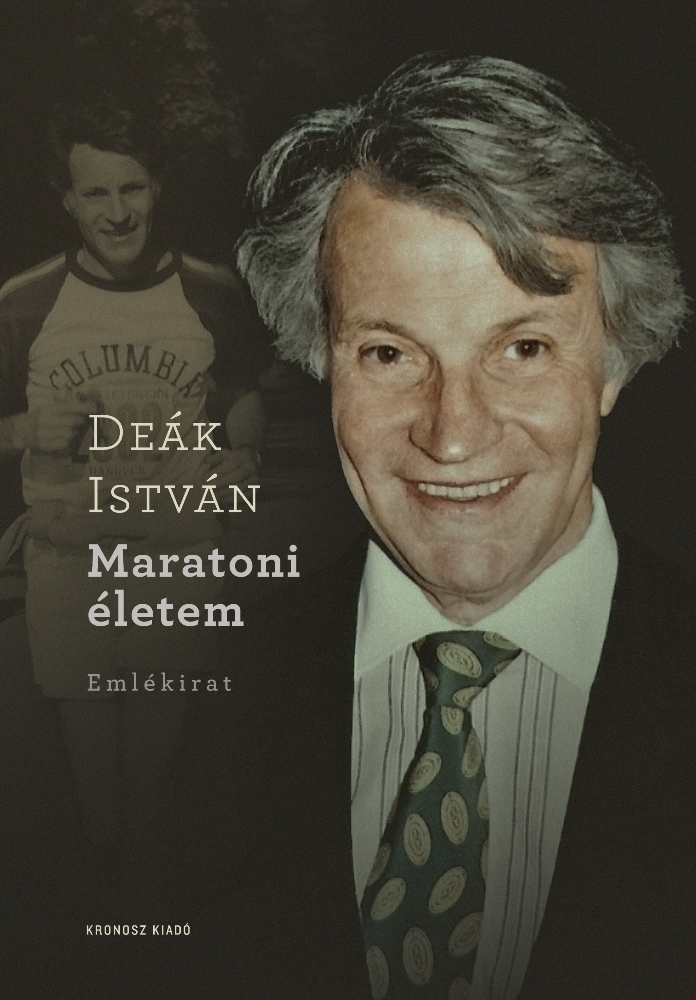

The remarkable life of the historian István Deák

Published by: Kronosz Kiadó

The late István Deák (1926-2023) was an innovative and accomplished scholar of Hungarian and Habsburg history as well as of the Second World War. As attested by the palpable grief and abundant fond memories shared upon his passing earlier this year, Deák – who was a professor at Columbia University for numerous decades – was a much-appreciated mentor and colleague to several generations of scholars. He was also a popular socialite and frequent contributor to highly reputed intellectual journals such as, most notably, The New York Review of Books and The New Republic.

István Deák left his native Hungary at the time of Stalinization, when he was in his early twenties, to spend the next three-quarters of a century mostly on the Upper West Side in Manhattan. Remarkably, in his old age, he chose to compose his detailed, fascinating, if also clearly incomplete memoir in his native Hungarian, which has been released posthumously. On the pages of this often delightful, even endearing, and at times rather indulgent book (“thanks to the Hungarian Arrow Cross, we fell in love”; “back then Americans were the saviors of the world – and maybe they still are today”), Deák focuses on the roughly first fifty years of his life. The manuscript ends rather abruptly with Deák’s contemporary reporting on his premier marathon run in 1977.

The book is divided into three major parts respectively titled “Hungary” (which fills more than half the pages), “Paris-Munich”, and “America.” While in the last part Deák devotes some attention to his scholarly career, contributions, and milieu, his memoir is more engaging, and more revealing too, when recalling his eventful and rather exceptionally fortunate life in mid-twentieth-century Europe. With his humane insight, consistent questioning of clichés, fine sense of humor and evident appreciation of life’s bounty, Deák’s memoir helps us experience and reconsider the high dramas and tragedies of those years. Maratoni életem thus amounts to a personal history of the highest caliber, which is only occasionally enriched by the greater retrospective awareness – and the at times necessary correctives – of the professional historian.

Rather characteristically, he first noticed that German bomber planes were flying above his head while swimming in an opulent Budapest bath house.

From an upwardly mobile family of Jewish origins that still hoped to pursue “complete assimilation” into Hungarian society in an age of racial exclusion and worsening violence, Deák belonged to a narrow layer of upper middle-class youth in the heavily stratified society of interwar Hungary. As he aptly remarks early on, his family lived “shamelessly well” under much of the regency of Miklós Horthy (in the original: szégyenletesen jól). Having had a Catholic upbringing, Deák was apparently barely aware of Judaism in his early youth (Orthodox Jews struck him as “if they came from a foreign world” even in 1944) and, more remarkably, barely encountered antisemitism personally. Rather characteristically, he first noticed that German bomber planes were flying above his head while swimming in an opulent Budapest bath house.

Not necessarily perceived as Jewish by others, István Deák soon had to endure physical violence at a cultural venue. He ended up toasting with champagne on the day of his Abitur – which had been rescheduled to April 1944 – when his father had already been captured by the Nazis, and he himself was expecting to be imminently called up as a so-called labor serviceman. A boy scout ordered to display the yellow star earlier in that devastating month, he chose to wear Hungarian national dress on the day of his exams while refusing to place the stigmatizing star on it. As he himself notes, this was, depending on the perspective, a courageous act of resistance or an act of betrayal that helped further isolate his persecuted fellow students.

While their dream of complete assimilation was most brutally destroyed, his family’s high degree of social integration, unusual resourcefulness, sheer luck and, above all, the heroic sacrifice of close acquaintances – most importantly, that of the boyfriend of István’s older sister, Éva, the journalist Béla Stollár, who was subsequently murdered by members of an Arrow Cross militia – proved crucial in the Hungarian year of extermination. In combination, they meant that nearly his entire family survived the Holocaust – though not his grandmother, for which István, in a rather typical example of the guilt of survivors, continued to blame himself. Remarkably, they were not much harmed materially: as Deák recalls, they entrusted their belongings to seventeen different acquaintances and had “everything returned” upon the defeat of the Axis. Such fortunate and even positive experiences were exceedingly rare in the Hungary of these years.

They taught the later historian never to trust arguments about “historical necessity” and made him acutely aware of the dilemmas and frequent moral ambiguities of collaboration and resistance – a subject upon which he published his most successful book, Europe on Trial more than six decades later. It belongs to the full story, though it is an aspect which Deák’s memoir only briefly mentions, that Béla Stollár’s memorial plaque has been repeatedly vandalized in post-1989 Hungary as it supposedly honors “communist resistance.”

István Deák’s posthumous memoir also reveals how closely his other main scholarly interests – whether questions of nationalism and emancipation or the social history of the Habsburg army – related to his own and his family’s characteristic experiences, roles, and cherished beliefs. Whereas today’s younger scholars tend to perceive the Habsburg Empire as belonging to an epoch long gone, albeit one which has left many intriguing legacies, its presence still felt immediate in Deák’s youth. His special insights, evident popularity, and notable impact as a US-based scholar arguably largely derived from his ability to connect worlds that otherwise seemed so far apart, to connect the Central Europe of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to that of New York and, more generally, the Western world in the late twentieth. Deák’s urbane personality and experience-based but also instinctive opposition to Nazism, Bolshevism, and ethnic nationalism provided key bridges here, even though, as he willingly admits, he never felt at ease among the more philosophically minded intellectual progressives of New York (he might have been too upper class and too strongly shaped by his Christian upbringing, he ponders).

Deák also discusses his infamous expulsion from Hungary in the 1970s, and how he would soon fly back to the country as part of the US delegation returning the Holy Crown – without appearing in any of the photographs printed in the regime-controlled press.

Deák sounds remarkably modest when discussing how he acquired his PhD at age 36 (it was actually a “PhT” as his wife, Gloria “Pulled Husband Through,” he writes), how he would receive tenure and head a small institute at Columbia (in the wake of “Sputnik fever” his former supervisor, Fritz Stern, who was his senior by only three months, helped him into a newly opened position for which he was not eminently qualified at the time, he explains), and career as a scholar (his major research monograph during the Cold War, which explored the Hungarian and Habsburg history of 1848-49 in original ways, was a hybrid of the scholarly and the popular, the objective and the polemical, he argues rather disarmingly). Deák also discusses his infamous expulsion from Hungary in the 1970s, and how he would soon fly back to the country as part of the US delegation returning the Holy Crown – without appearing in any of the photographs printed in the regime-controlled press.

Previously much less familiar were István Deák’s years between his time in Hungary and the US (1948 to 1956). The reputed historian of later decades spent those years as a promising but not too successful – and mostly simply uncommitted – Parisian student and bookseller, and then as a Cold Warrior active at the Hungarian desk of Radio Free Europe in Munich, with special privileges, a rather uncertain legal status, and close relatives on the other side of the Iron Curtain. With an unusually open mind and clear sense of irony, he compares his experiences in early postwar West Germany rather favorably with those he had in France. As he calmly recalls, he also befriended people in Bavaria, including fellow Hungarians, who would have persecuted him just a few years earlier.

More generally, this captivating memoir is a splendid testament to what István Deák aptly calls his “patriotic enthusiasm, numerous sour experiences, and objectivity fostered by coerced distance.”

Deák also reflects on how in the mid-1950s, and probably not unrelated to his anti-communist political activism, his parents were forcibly resettled to a remote village in Hungary – and how his mother passed away before he was able to visit and see her again, a source of his recurrent bad dreams afterwards. The moral complexity and ambiguity inherent in this painful story will certainly not be lost on the memoir’s readers. They point directly to the kinds of complications Deák did so much to analyze in his later years as a scholar.

More generally, this captivating memoir is a splendid testament to what István Deák aptly calls his “patriotic enthusiasm, numerous sour experiences, and objectivity fostered by coerced distance.” It helps us reflect on diverse human situations and interactions, where passing facile judgement can only prove inadequate – and shows how those “numerous sour experiences” did not break its author’s generous spirit.

Ferenc Laczó is an assistant professor with tenure (universitair docent 1) at Maastricht University, a visiting assistant professor at Columbia University in 2023-24, and an editor at the Review of Democracy (CEU Democracy Institute). He is the author or editor of twelve books on Hungarian, Jewish, German, European, and global themes.