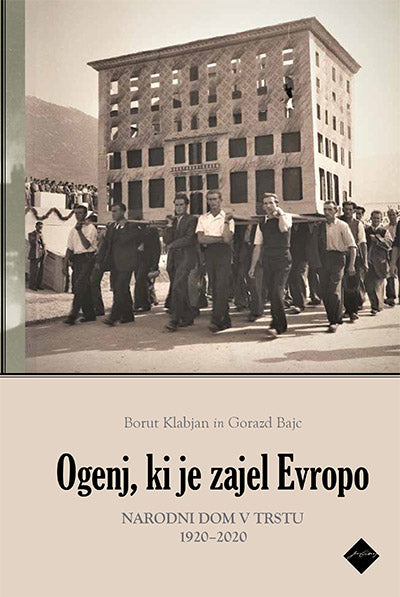

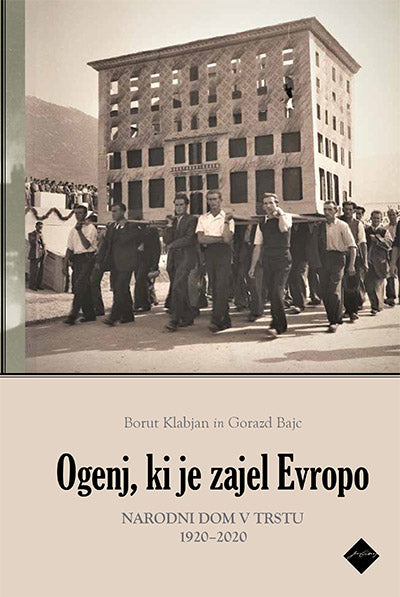

The Trieste arson that engulfed Europe

The Narodni Dom featured on a postcard. Public domain.

The Narodni Dom featured on a postcard. Public domain.

Published by: Cankarjeva založba

The Narodni Dom featured on a postcard. Public domain.

The Narodni Dom featured on a postcard. Public domain. Ogenj, ki je zajel Evropo, the title of Borut Klabjan’s and Gorazd Bajc’s volume, translates into English as “The Fire that Engulfed Europe” and is an apt metaphor for the story it tells: On 13 July 1920 the Narodni dom in Trieste, which housed several associations working in Slovene and other Slavic languages, a Slovene bank, Trieste’s largest Slovene-language newspaper Edinost, a hotel, as well as other institutions, fell prey to fascist arson. Built in 1904 and designed by well-known architect Maks Fabiani, the Narodni dom was the center and the symbol of Slovene life in the city of Trieste, as well as of other Slavic nationalities, such as the city’s Serbs and Czechs. The Austro-Hungarian Empire ended with the Great War. In October 1918 the first South Slavic state, later Yugoslavia, was one of the states founded from its rubble. Trieste and its wider hinterland, however, were occupied a few weeks later by the Italian army and in the autumn of 1919 became part of Italy. A scarce year into this annexation, fascists attacked the central symbol of non-Italian multiethnic life in the city. The attack on the Narodni dom in July 1920 targeted precisely Trieste’s multiethnicity and thus represents one of the earliest expressions of the violence that would lead to the destruction of multiethnic life in Europe over the subsequent decades, including the Holocaust. Klabjan and Bajc succeed in telling a European story through the looking glass of a single event – its coming about, its happening, its legacy.

The two authors congenially combine their respective expertise and process a truly impressive amount of material, gathered from archives in Belgrade, Berlin, College Park in Maryland, Ljubljana, London, Nantes, Pazin, Rome, Trieste, Washington DC, and Zadar. In addition, they consulted 40 newspapers, conducted twelve testimony interviews, and used a host of published sources. Over nine chapters, they unfold the history of Trieste’s Narodni dom applying historiographic scales that go from the local to the national to the transnational and the European.

Readers are introduced to the complex entanglements of space, people, society and (changing) citizenship in Trieste’s late imperial and early post-imperial history.

The first four chapters establish the context that led to the events of July 1920: Trieste’s emergence, since the 18th century, as the Habsburg Monarchy’s cosmopolitan port; it being the home, by the beginning of the 20th century, of the biggest Slovene urban population anywhere; the national conflict that characterized the late imperial city; the significance of the Narodni dom for the Slovene and wider Slavic bourgeoisie; the First World War and the effects of the nearby front on the Isonzo; the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; the international context of the Paris Peace Conference, where neither Slovenes nor Croats were represented by any state; and the “Adriatic Question” of how to draw new state borders. Readers are introduced to the complex entanglements of space, people, society and (changing) citizenship in Trieste’s late imperial and early post-imperial history. The experience of the Great War had fragmented and brutalized the local society, and the power vacuum that followed the end of more than half a millennium of Austrian statehood was instrumentalized by those who had founded the first fascio di combattimento in the city already in 1918.

The core Chapter Five, “The Fateful Summer of 1920”, comprises 115 of the altogether 396 pages of text. The authors meticulously reconstruct how violence was part and parcel of the Italian takeover of the city which had ensued in killings even before the “fateful summer”; how state police stood by or even collaborated in this violence; and, after the attack of 13 July 1920, how propaganda was used to cover up events, including the invention of a depot of hidden weapons in the Narodni dom, and more generally a “Slavic threat” both in Trieste and from the neighbouring new Yugoslav state. On 3-4 August 1919, Italians had burnt Slovene and Czech books. The libraries of Slovene and other Slavic cultural associations had been destroyed, as had schools, banks, and the editorial office of the Edinost (pp. 138-140). A year later, the Narodni dom was set on fire.

The subsequent three chapters cover the period after the arson to the end of the allied government of the Free Territory of Trieste in 1954: the two decades of fascist rule; the Second World War; its aftermath. Quests for compensation for lost property were never fulfilled; maintenance, let alone reconstruction, was at a perpetuated impasse. When the British and Americans arrived in Trieste in June 1945, they took up quarters in the remains of the Narodni dom. It was they who, for the first time, attempted to estimate the damage that had been perpetrated in 1920.

Quests for compensation for lost property were never fulfilled; maintenance, let alone reconstruction, was at a perpetuated impasse.

The last chapter covers the period since 1954, when Trieste became a part of Italy again. The authors make it quite clear how it literally took a century to come anywhere near to making things right. The postwar Italian state was founded on a positive self-image of the resistenza, the resistance against both fascism and the national socialist occupiers in 1943-45. In addition, the northeastern border region was marked by tens of thousands of people, mostly ethnic Italians, who during the first postwar decade had left the former Italian territories, which were now in Yugoslavia. The traditionally prejudicial image of the “Slavs” came to overlap with the image of the enemy “communists”. There was little communicative space for the fact that fascism’s victims merited recognition and recompensation and this was true long beyond the Cold War.

After communism’s end, Slovenia joined the European Union in 2004 and the Schengen Agreement in 2007, literally dissolving the hard political border with Italy. Ironically, in Italy, discourses previously harbored only by the far-right have become state-endorsed, and the political abuse of past events has re-triggered historical traumas (p. 393). After decades of negotiating and drafting, the law on the protection of the Slovene minority in Italy was finally adopted in 2001. Still, it was to take another 20 years and several symbolic acts on the national and European political stages, before, on 13 July 2020, the presidents of Italy and Slovenia ceremonially signed the memorandum that restored the building that had housed the Narodni dom to Trieste’s Slovene community, commencing the procedure of restitution. The reason for the difficult legacy of the July 1920 attack, the authors comprehensively explain, is that it came from within society itself. It could hardly be assigned merely to fascist radicals, whitewashing the urban (Italian) majority. After 1918, Trieste’s rapid downfall from its imperial grandeur could not have been more complete.

There is a productive tension in the narrative that is never resolved: The authors distance themselves from any idea of monolithic national bodies, and thus also from the nationalist Slovene narrative attached to the Narodni dom (p. 15). But they also make it very clear that their story is about violence against Slovenes because they were Slovenes, and that the barbaric act of arson and destruction was the outpost of a larger history of violence and persecution. Thirdly, Klabjan and Bajc are aware that they are implicated researchers: “Fabiani’s palazzo is the foundation that enables the Slovenes to say that Trieste is also ours” (p. 14). Not only have they accomplished a comprehensive history of early fascist violence against Trieste’s Slovenes; they also have written European history at its best. The arson of 13 July 1920 as a metaphor for the “fire of intolerance” (p. 7) that would engulf and incinerate Europe makes much sense.

Il Mulino published an Italian-language edition of the book in 2023, under the title Battesimo di fuoco. L’incendio del Narodni dom di Trieste e l’Europa adriatica nel XX secolo. Storia e memoria.

Sabine Rutar is a Senior Researcher at the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies in Regensburg, Germany, where she works as Editor-in-Chief and Managing Editor of Comparative Southeast European Studies. In 2022/23 she was acting Professor of Global History at the University of Potsdam. She recently edited, with Anna Wylegała and Małgorzata Łukianow, No Neighbors’ Lands in Postwar Europe. Vanishing Others (Springer Palgrave 2023) and, with Paolo Fonzi and Xavier Bougarel, Food, Scarcity and Power in Southeastern Europe during the Second World War (Bloomsbury, forthcoming autumn 2024).

Ogenj, ki je zajel Evropo. Narodni dom v Trstu 1920-2020 [The fire that engulfed Europe. The National House in Trieste 1920-2020.]

Published by: Cankarjeva založba