The unknown story of the Soviet Eastern International

Published by: Oxford University Press

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Vladimir Putin’s overtures to countries in the Global South to join Russia in an anticolonial struggle against “Western imperialists” left many observers puzzled. After all, launching a brutal, invasive, colonial war in Ukraine seems fundamentally incompatible with the rhetoric of anticolonialism. However, Putin’s appeal draws on the historical narrative of the Soviet Union and its legacy of championing global anticolonial movements, particularly among non-Western nations. By invoking this past, he seeks to underscore the continuity between Soviet and post-Soviet foreign policy in today’s geopolitical landscape. This complex interplay between history and contemporary strategy is the subject of a new book by Masha Kirasirova, Assistant Professor of History at New York University Abu Dhabi. Her work examines the origins, evolution, and enduring impact of the Soviet Union’s so-called “Eastern International,” and sheds light on how this anticolonial project continues to influence Russian foreign policy.

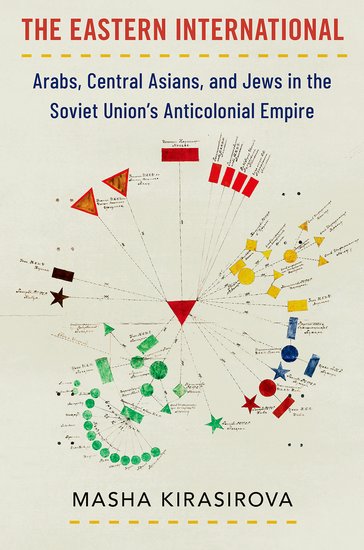

The cover of the book is striking, with a vivid diagram of the Turkestan Bureau of the Communist Party. The central red triangle symbolizes the Bureau, which connects various political organs, executive committees of the Communist International, and informant centers in Tehran, Kabul, Baku, Moscow, and other locations. This design represents the anticolonial “Eastern International” and emphasizes the role of the Turkestan Bureau in the envisioned global communist revolution, in which the former colonial territories of the Russian Empire would play a key role in spreading Bolshevik ideology. It also underscores a central idea of the book which seeks to explore the crucial role that the USSR’s “domestic East” played in spreading the ideals of a global anticolonial communist revolution to the “foreign East.”

A notable feature of Kirasirova’s book is its focus on the biographies of lesser-known or obscure individuals who played crucial roles in the “Eastern International.”

Kirasirova’s book examines how the Communist state and its intermediaries deployed the concept of the “East” (vostok), tracing the history of interactions between the “two Easts” from the 1920s to the current Russo-Ukrainian war. The “domestic East” referred to the predominantly Muslim Soviet republics in Central Asia and the Caucasus, while the “foreign East” encompassed regions of Soviet interest in South and East Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The hierarchy between the “Easts” was shaped by Soviet narratives of legitimacy, in which stories of the overcoming of Russian colonialism, the emancipation of women, and the modernization of the former colonial territories of the Russian Empire in the “domestic East” were central to the global promotion of anticolonial communist ideals. Kirasirova emphasizes, however, that despite the USSR’s anticolonial stance, it inherited many structural and discursive elements from the Russian Empire and consciously adopted practices from Western European empires.

Kirasirova argues that the “Eastern International” project broadens the understanding of the Soviet Union’s international positioning by highlighting how Central Asia, as the “domestic East,” allowed Moscow to present itself as an anticolonial empire that addressed the challenges faced by national anticolonial movements in the “foreign East.” The book is divided into seven chapters, each dealing with a different facet of the “Eastern International.” These include the transformation of colonial Turkestan into a center of global communist revolution, the role of the Communist University of the Workers of the East as a revolutionary laboratory, the politics of national identity during the Great Purges, Soviet interactions with Arab communists in the postwar period, the impact of Khrushchev’s thaw on nationalist movements, and the decline of the project in the 1970s and 1980s. Kirasirova also examines the continuing influence of the “Eastern International” on the domestic and foreign policies of post-Soviet Russia.

A notable feature of Kirasirova’s book is its focus on the biographies of lesser-known or obscure individuals who played crucial roles in the “Eastern International.” One such figure is Konstantin Troianovskii, a Jewish Bolshevik activist who was instrumental in establishing the project. Troianovskii envisioned a network linking Moscow with Turkey, Iran, and other Arab countries through strategic hubs, such as Tashkent and Bukhara. His Jewish background initially influenced the project, but by the early 1930s Arabs and Central Asians had become the main participants, reflecting a shift in Soviet nationality policy and the rise of ethno-nationalism. This development reduced the influence of Russian Jews in representing the “domestic East,” but created opportunities for Central Asian representatives to advocate for their republics on the international stage. At the same time, Zionist immigration to Palestine and the establishment of mandates in Iraq, Syria, and other parts of the Arab world not only fueled anticolonial sentiments but also raised the national awareness of local activists, which in turn supported the global communist revolution. The Great Purges of the late 1930s had a profound effect on Central Asian and Arab cadres. Kirasirova describes how figures such as the Uzbek statesman Nuritdin Mukhitdinov and the Arabist Yevgeny Primakov navigated these upheavals. Mukhitdinov observed the fabricated confessions of Uzbek national cadres and realized that national revival could only take place within the constraints imposed by Moscow. Primakov, a Jewish Soviet official dealing with the Arab world, hid his heritage to advance his career.

She demonstrates how Central Asian republics reinterpret their histories through postcolonial lenses, often obscuring complex realities. Putin’s regime, on the other hand, suppresses critical historical analysis while reviving anti-Western rhetoric.

The shift in Soviet policy following Stalin’s terror dramatically altered the “Eastern International” and its ideological framework. By the late 1930s, the USSR’s narrative had shifted from condemning Russian colonialism to promoting “friendship of peoples” and portraying Russian expansion as a progressive force, limiting how the Central Asian republics could portray their history and restricting national activities to conform to Stalinist ideals. Kirasirova emphasizes that the restrictive discursive frameworks for discussing colonialism continued to constrain actors from the “domestic East” even as their resources expanded after the Second World War. While figures from Lebanon, Algeria, Syria, and Egypt looked to the USSR as a beacon of anti-fascism and anti-Westernism, the Soviet Union maintained a confrontational stance toward socialist nations, including through interventions in Eastern Europe. To maintain the USSR as a symbol of an alternative modernity, instances of anti-cosmopolitan repression were conveniently overlooked.

Postwar cultural diplomacy saw increased interactions between the Soviet Union and the “foreign East” through film festivals and cultural congresses. However, these interactions were limited by Soviet ideological constraints, and Central Asian filmmakers faced obstacles when their works criticized Russian colonialism. In the 1970s, writers such as Olzhas Suleymanov and Chingiz Aitmatov began to challenge Soviet stereotypes, but the influence of many major Arab communist parties had already waned. As the USSR faced geopolitical challenges, including conflicts with Islamist movements, the “Eastern International” began to unravel and largely disintegrated in the 1980s and 1990s, coinciding with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Kirasirova concludes by examining the lasting impact of the “Eastern International” on post-Soviet politics and intellectual frameworks of decolonization and nationalism. She demonstrates how Central Asian republics reinterpret their histories through postcolonial lenses, often obscuring complex realities. Putin’s regime, on the other hand, suppresses critical historical analysis while reviving anti-Western rhetoric. Adapting to the post-Soviet era, Arab politicians and intellectuals have shifted their focus to new geopolitical challenges.

The Eastern International serves as a compelling case study for reconstructing the lesser-known history of the Soviet Union’s global anticolonial efforts. Kirasirova offers a detailed account of the Soviet Union’s global anticolonial efforts and the role of Central Asian figures within the “Eastern International.” She provides valuable insights into the complexities of Soviet statecraft and its impact on global and regional politics. Although the Soviet Union remained an empire in a revised form, its anticolonial ambitions fostered a network of interactions with the Global South that engaged Central Asian representatives in international relations. This engagement continues to influence these republics as they navigate their historical dependencies on Russian imperialism.

Aleksandr Korobeinikov is a research associate at the Institute for East European Studies at Freie Universität Berlin and a doctoral student in the Department of History at the Central European University in Budapest and Vienna. He is a historian of Russia and Siberia with a special emphasis on the late imperial and early Soviet Yakut (Sakha) region. He has authored multiple articles delving into the history of Sakha intellectuals and their role in shaping the political landscape during the postimperial transformations of the Yakut (Sakha) region.