Tracing the missing in the Arolsen Archives

Published by: Oxford University Press

Few outside the field of Holocaust Studies will have heard of the Arolsen Archives, or, as they were formerly known, the International Tracing Service (ITS). Yet, their work and documents provide a powerful insight into the history of both the Holocaust and the post-war world. In his new book, Fate Unknown, Dan Stone sheds light on the breadth and depth of the Arolsen Archives collections and reveals how they enhance our understanding of the past. The book is both a history of the period and a reflection on its sources, making substantial empirical and methodological contributions to the field.

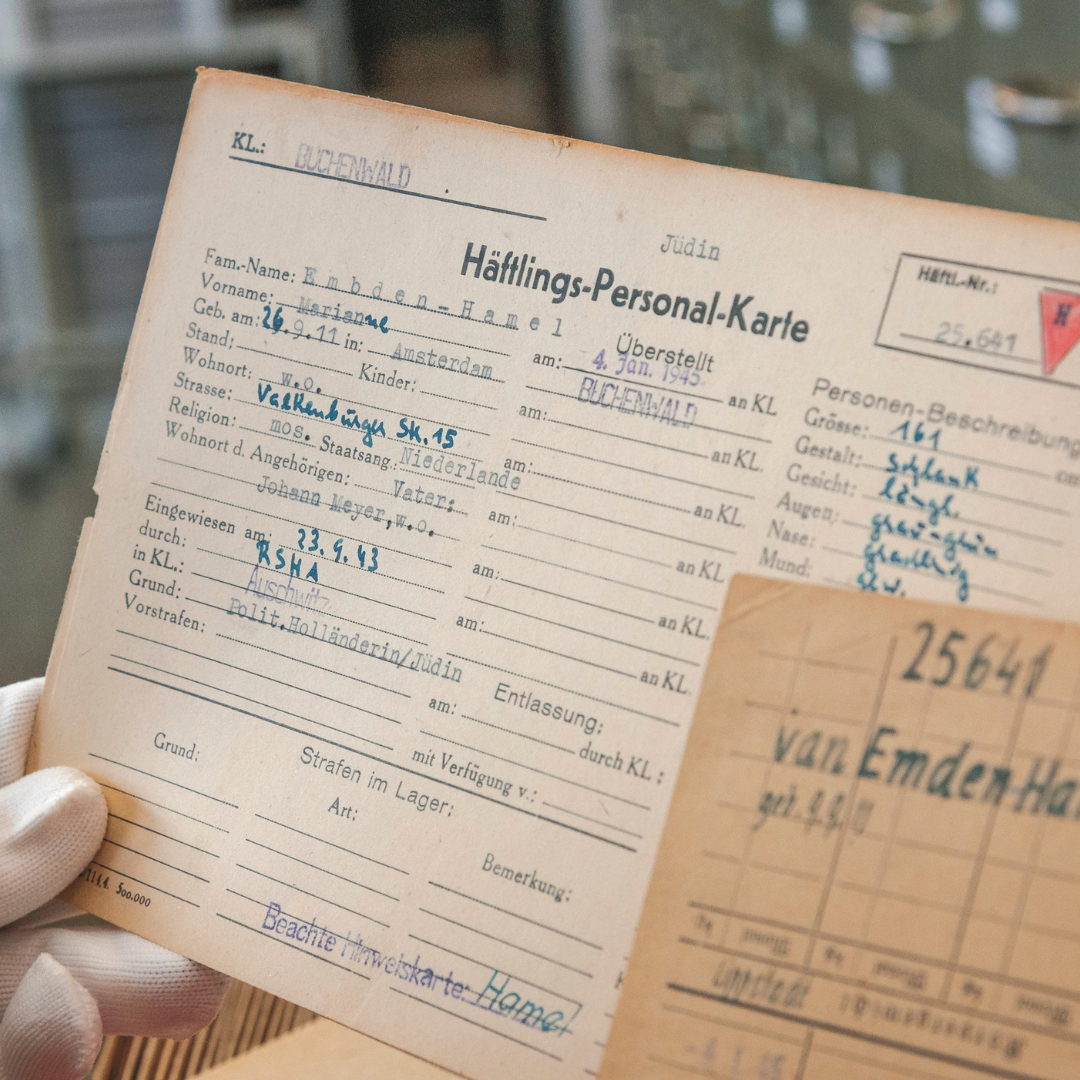

The Arolsen Archives contain over 30 million files, index cards, and lists concerning Holocaust victims and concentration camp prisoners. They also hold 3 million files of post-war correspondence on individual victims of persecution. The jewel in their crown, however, is the Central Name Index – a collection of over 50 million index cards used for tracing victims and survivors. Until the archives were opened to the public in 2007, these documents were used almost exclusively by ITS staff who answered inquiries from survivors and their families and supported legal cases. Since transforming into the Arolsen Archives, researchers both online and at access centres across the world have been able to use the material and the institution’s powerful search tool to discover new histories from this dark past.

Fate Unknown is a book about sources which reflects on how we do historical research about the Holocaust.

Fate Unknown is split into eight chapters, which follow three themes. The first chapter charts the complex institutional history of the ITS in its first decades, emerging from cooperation and competition between various national tracing bureaux and the different international institutions that had responsibility for displaced people. The second, third, and fourth chapters cover what the Arolsen Archives tell us about the Holocaust, including a collection of archival discoveries (chapter 2), the organisation and experiences of the sub-camp systems in Auschwitz and Gross-Rosen (chapter 3), and death marches and liberation (chapter 4). The second half of the book is devoted to the post-war experiences of survivors and the work of the ITS. It charts the efforts to document victims’ graves and bodies (chapter 5), the searches for survivors within the system of displaced persons camps (chapter 6), the post-war lives of certain groups of survivors (chapter 7), and the work of the child search branch of the ITS in reuniting children with their parents (chapter 8).

In an earlier work, Stone argued that the Arolsen Archives should be used to tell a social history of the Holocaust. In a way, this book answers his own call. By presenting the experiences of Holocaust victims and survivors, Fate Unknown tells a history of the Holocaust that is deeply personal. Stone traces individuals through the various parts of the ITS – in concentration camp documentation, refugee and displaced persons administration records, and tracing efforts – reconstructing their lives as best as possible. The sheer number of personal histories that Stone includes in the book is staggering. He deploys individual experiences at every turn possible, giving us an insight into the subjectivities of these events as well as their history. This approach is, at times, overwhelming. Yet it is a testament to the amount of material in the Arolsen Archives that a book this full of histories merely scratches the surface of what exists.

As well as these empirical insights, Fate Unknown is a book about sources which reflects on how we do historical research about the Holocaust. Stone observes that: “ITS acts as a kind of echo chamber of Holocaust research in general: we find millions of documents yet they are not what we want” (p. 337). In order to answer the “fundamental questions”, Stone argues, we need to “move from documents to human beings”. While material in the Arolsen Archives enables us to reconstruct much about victim’s lives, “they are pieces in a larger puzzle” that sit alongside their own texts, eyewitness statements, and interviews.

Because of this, it would be easy to pigeonhole the Arolsen Archives as merely a collection of documents from the former concentration camps. Indeed, for decades many historians showed little interest in the ITS collections, believing them to be useful only for tracing. Stone’s book, however, reveals the true diversity of their holdings, drawing attention to previously unknown sources. Particularly interesting are the unusual sources about the concentration camps. In addition to many “perpetrator” documents about the camps’ administration, the archives also hold camp maps drawn by survivors, as well as early post-war “testimonies” given to the ITS (pp. 132-42). These sources exist because the ITS collected information from survivors about different camps to aid their tracing efforts. Stone repurposes these documents as part of his social history, revealing how material that was designed for tracing can tell us much more about survivors’ lives and experiences. This innovative use of sources is one of the main contributions this book makes to the field, changing the way we think about the Arolsen Archives.

Stone paints a picture of the graves recheck that spans multiple layers: from the demands and priorities of the United Nations and International Refugee Organisation who controlled the operation, to the field officers who visited locations, to the German mayors who provided maps and drawings of graves in their areas.

Indeed, Stone criticises some of the early ITS staff for their “remarkable failure of the imagination when it comes to interpreting” their documents (p. 270). He shows how some staff took camp doctors’ certifications that prisoners were fit and well at face value, faithfully reproducing what they found in the files to the detriment of the actual situation. He also reveals how the Cold War influenced the ITS’s work, as the organisation gave preference to refugees fleeing Communism (p. 284). Throughout the book, therefore, Stone highlights the challenges of interpreting documents in the Arolsen Archives. While he does not explicitly lay out a methodology for interpreting them, Stone demonstrates how being aware of multiple contexts – historical, archival, and political – reveals more from the sources than first meets the eye.

Stone’s account is one that brings together the micro with the macro. He describes how the ITS worked with other organizations, including local authorities, occupying forces, and international institutions, while having a direct impact on small localities. The “graves recheck” programme is a good example of this (see chapter 5). Started in the summer of 1945 by the Belgian and French tracing bureaux and then centralized in October 1945, this programme sought to identify the locations of graves and identities of those buried in them. Stone paints a picture of the graves recheck that spans multiple layers: from the demands and priorities of the United Nations and International Refugee Organisation who controlled the operation, to the field officers who visited locations, to the German mayors who provided maps and drawings of graves in their areas. As a result, this book applies multiple scales of analysis simultaneously, bringing together histories of the Holocaust, post-war Germany, and international institutions.

Fate Unknown tells the history of an institution, of a people, and of an archive, all within the complex and shifting context of post-war politics. It is a remarkable synthesis of history and source reflection. Stone charts the history of survivors as they sought to confront what he once termed the “sorrows of liberation”. This book reveals the organisations that helped – or sometimes hindered – survivors in the post-war world, drawing together perspectives from across Europe and from different experiences of reconstruction. It also presents the history of the International Tracing Service, from its chaotic beginnings to its transformation into an archive. Throughout, Stone uses material from the Arolsen Archives, reinterpreting sources that have long been used simply for tracing to, instead, tell a social history. His contribution to our understanding of the International Tracing Service, both as an institution and an archive with enormous potential, is immense. As researchers grapple with how to make the most of the Arolsen Archives, Stone provides a leading light.

Barnabas Balint is a doctoral candidate at Magdalen College, University of Oxford, under the supervision of Professor Zoe Waxman. He has held Research Fellowships at the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research, the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure and the Institute of Historical Research, University of London. His research focuses on developing age as an intersectional category of analysis for Jewish youth in Hungary during the Holocaust.