Ukrainian cinema in the spotlight during the Soviet Thaw era

Published by: Bloomsbury Publishing

It is not the usual practice to review a book eight years after it was published. In the current circumstances, however, it makes perfect sense. In 2022, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I sought to learn more about Ukrainian cinema, only to discover that the pattern of the Cold War era of Slavic film studies in the West — which engaged mainly with Russian film — had continued unperturbed. Just a few rare pieces of scholarship had tried to break the mold, by focusing on the cinema of the former republics. The book under review, published in 2015, turned out to be the only systematic study dealing with the cinema of Ukraine to have appeared in the English language in the three decades following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The only other study dedicated to Ukrainian cinema I know of is the French-language Histoire du cinéma ukrainien, 1896-1995 by Lubomir Hosejko (Editions A Die, 2001). Whatever other scholarship there is, is in Ukrainian or Russian languages.

It is in this context that I undertook it to learn more about Ukraine’s cinema, especially as I noticed the country does not even feature as a separate entry in the British Film Institute’s Companion to Eastern European and Russian Cinema (published in 1999), nor is it mentioned as an independent country in the introduction to Wallflower Press’s collection on The Cinema of Russia and the Former Soviet Union (published in 2007). Against such background, Joshua First’s monograph does stand out as a progressive, even if lonely voice. Reading Ukrainian Cinema assisted me in discovering and navigating a number of little-known, yet amazing films made in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic during the 1960s and the 1970s.

Three of the world’s oldest film studios were based on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR: those in Yalta and Odessa were founded in 1919, whereas the Dovzhenko Film Studio in Kyiv dates back to 1927. In his book, Joshua First focuses on a key period in the works of the Dovzhenko Studio, which roughly covers “the long 1960s”, give or take, a period of relative “thaw” and a decisive — even if not particularly successful — period in the struggles of finding an artistic expression of Ukraine’s national identity, as revealed in key productions made in Kyiv. What the book covers is just a fraction of what Ukrainian cinema is, of course — and I imagine that the catch-all title was suggested by the editors in the absence of other, more comprehensive surveys on the matter. First’s investigation — which does the right thing to maintain a good focus rather than spread itself too thinly — was originally defended as a doctoral thesis at the University of Michigan in 2008.

I like books about the history of cinema written by historians. Rather than simply offering textual analysis, the historical studies uncover important details of the ideological context and the production background of films; I wish there were more such works. Indeed, the approach of historians also has its shortcomings — usually in that it does not engage enough with the formal and stylistic aspects of the films, and it rarely places the films in a wider transnational context. This study is marked both by the same advantages and shortcomings of the approach. In this review, I feel it is more productive to foreground the advantages.

First does a remarkable job in systematically detailing — by zooming onto the politics at Dovzhenko studios and by digging deep into the archives — how efforts for the self-expression of Ukraine’s identity in folkloric and poetic cinema were subtly turned mediocre and provincialized, and how — in a later period — the careers of its brightest and bravest such as directors like Yurii Illyenko, Leonid Osyka, and actor-director Ivan Mikolaychuk were thwarted. It is nothing short of a miracle that they managed to make remarkable films such as The Stone Cross (Osyka, 1968), The Eve of Ivan Kupala (Illyenko, 1969), or Babylon XX (Mikolaychuk, 1979).

The book is full of riveting reports of the deeds of various literary dissidents such as writers Ivan Drach, Dmytro Pavlychko, Lina Kostenko and others of the so-called shestidesyatniki, the Sixtiers, most of whom were involved in cinema as screenwriters, of the difficult position of Ukraine’s Communist Party Secretary Petro Shelest (in office 1963-1972) and of the interaction (just short of “battles”) between the studio’s head Tsvirkunov and the authorities at Goskino and other Moscow-based institutions in regard to budgets, staffing, and approval processes, all part of the “nationalities politics” of the center.

First’ attention to clarifying matters of linguistics — related to the decision to making films in the Ukrainian or the Russian languages — that linked dubbing practices with financial viability (as only films dubbed into Russian would be distributed Soviet Union-wide) is of great value. It is an extremely complex, multifaceted, and comprehensive investigation. I admired the detailed case studies of the production history of several films that never saw the light of day and the observations that First offers of a whole generation of directors of Ukrainian descent who seem to have had undergone serious “Russification” before being allowed to return to work in Kyiv but then ended up re-embracing Ukrainian identity politics.

One of the most valuable discussions was the story related to the making and then the release of Sergei Paradjanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors — a singular case of triumph in spite of all the controversies that surrounded it — as this is perhaps the only film of poetic cinema beyond Dovzhenko’s classics like Zvenigora (1928) and Earth (1930) that was not destroyed by censorship. First has also published a separate short monograph on this film in 2016.

Joshua First reveals how Ukrainian cinema existed within the structures of the Soviet film industry whilst it was kept from interacting with world cinema. Its leaders did not have the power to submit films to festivals directly — it seems that such direct submission only took place in the case of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, which also explains the international triumph of the film. On the contrary, a masterpiece like Illyenko’s White Bird Marked with Black (1971) was never sent out to any festival and was shelved in the Soviet Union even if it had somehow managed to win the top award at the Moscow International Film Festival before it was made to disappear.

In unpacking distribution histories, First does give a good range of detail showing which Ukrainian films were shown across the Soviet Union in the 1960s and how they performed at the box office. There is one more dimension that does not feature in the book but which I would like to briefly add, on the basis of my expertise as a festival historian. Namely, which Ukrainian films did the authorities in Moscow allow to be shown at Cannes, Venice or Berlin, the world’s three key film festivals? The answer is: none. During Soviet times, no Ukrainian film was ever submitted to any of the world’s top festivals.

Had it not been for the festival exposure, it is very likely that Paradjanov’s film would have been subjected to the same suppression as other masterpieces such as Illyenko’s 1965 Well for the Thirsty or Osyka’s 1966 Love Awaits Those Who Return.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, however, was submitted to the international film festival in Mar del Plata in Argentina, where it was acclaimed and from where it was picked up by many other festivals that screened it too; some also gave it awards. What is particularly important about this breakthrough is that the triumph at Mar del Plata in March 1965 happened some six months prior to Shadows’ premieres in Kyiv and Moscow (Fall 1965): the fact that the film was already acclaimed internationally sealed its fate. The genie was out of the bottle; this single showing at an international film festivals became a major factor in the film’s survival as it cushioned it from censorship. Had it not been for the festival exposure, it is very likely that Paradjanov’s film would have been subjected to the same suppression as other masterpieces such as Illyenko’s 1965 Well for the Thirsty or Osyka’s 1966 Love Awaits Those Who Return.

It was the investigations offered by First in this monograph that allowed me to grasp how the mechanisms of systematic suffocation of various national cinemas within the supposedly ‘multicultural’ Soviet Union worked to effectively keep away from view entire national film traditions. It is not by chance that on these matters First often cites Kyrgyz poet Chingiz Aitmatov, as identity suppression in the cinemas of the republics was, of course, not limited to Ukraine only.

As a film scholar I believe that Ukrainian Cinema is making a great addition to a still small — but hopefully growing — body of works that will break the pattern which uncritically equates Soviet and Russian cinemas and either “Russifies” or keeps the cinemas of the former republics in the shadow. As a historian of East Central European film, I wonder what would have been if the films of Ukrainian poetic cinema were seen internationally at the time of their making. Many of those films — some of which I discovered, belatedly, only due to being discussed in the book — are pretty much comparable in their aesthetic and sensibilities to other works of magic realism/surrealism that were made in the same period in neighboring Poland, Czechoslovakia, or Hungary. It goes beyond the objectives of Joshua First’s study to assessing the value of the Ukrainian masterpieces that remained unseen — it is enough that he reveals how and why these films remained unseen. It is up to film scholars to now watch these films and assess them against the background of the great Eastern European new wave tradition of the 1960s, so that they can take up their due place in the annals of cinema.

Dina Iordanova is Emeritus Professor of Global Cinema at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. She has published extensively on the film history of East Central Europe and the Balkans. She has also written on matters related to the way cinematic heritage is being renegotiated in the aftermath of former multicultural states, such as Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union — and continues this interest in the context of current developments in the post-Soviet space.

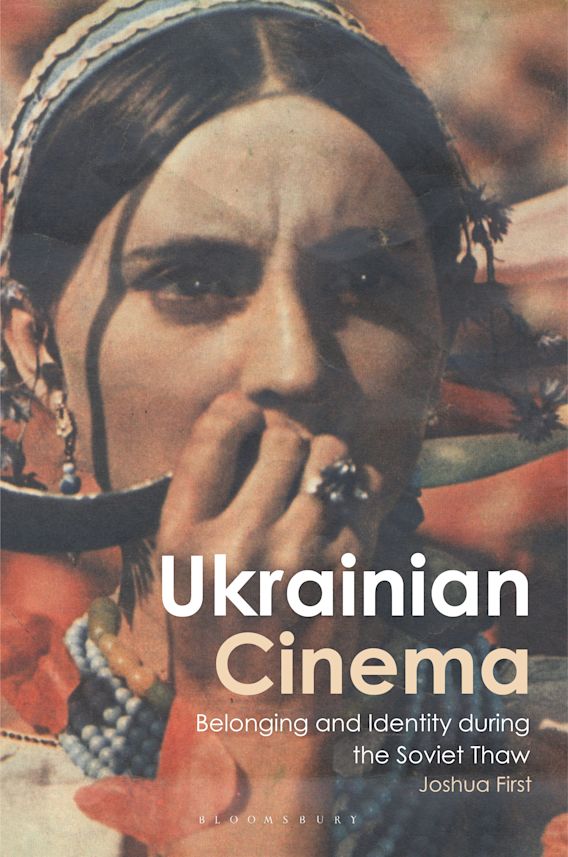

Ukrainian Cinema: Belonging and Identity during the Soviet Thaw

Published by: Bloomsbury Publishing